One of the many stories wrapped up in the Choix de Chansons is the abrupt and perhaps unhappy separation from the project of the great artist-engraver of the age, Jean-Michel Moreau Le Jeune, from the project after only one volume was completed.

Figure 1. A de Saint Aubin after C-N Cochin, Portrait of Jean-Michel Moreau, etching and Engraving, 1787, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

We know from the Prospectus. about which Robert Wellington has written elsewhere on the site, that Laborde imagined the visuals for this project not exactly as illustrations but more akin to improvisations derived from the songs themselves; moreover, they were part of the “multi-arts’ ensemble designed for all kinds of pleasure, visual, literary and musical. More importantly though, it was clear he was advertising the special expertise of “M. Moreau Le Jeune”— who was to be the presiding, unique creator of this enchanting visual world. It is worth reminding ourselves of this section of the text of that prospectus:

We call these picturesque songs, because they have given an ingenious artist the inspiration for a series of painted subjects, which he has designed and engraved with the greatest care: This collection will then have the triple advantage of amusing the mind, by its gay and interesting verses, of flattering the ear with easy and pleasant melodies, and finally to attract the eyes by scenes created with all that perfection that M Moreau is capable of.[2]

Moreau le Jeune, just let’s recall briefly, was regarded as the great engraver-designer of his age, in demand for not just his ability to conjure landscapes, but also fashion and a wide range of other modes and genres.[3] He had already made a sterling reputation in illustration suites for luxury editions of Ovid and other projects.[4] La Borde was clearly delighted to have secured (via his notoriously problematic financial dealings) this lynchpin of his vision. However, this essay begins with that mysterious falling out, the one that caused the rift that saw Moreau le jeune leave the Chansons project in abrupt and still baffling circumstances after only one volume of the projected four was completed. We are not exactly sure of the precise circumstances, but Adrien Moreau, in his biography of his ancestors published at the end of the nineteenth century, describes it thus: “Unfortunately, the character of the Chansonnier (La Borde) and the nature of the artist (l’humeur de l’artiste) did not accord. They split after one volume, following a violent scene”. [5] Perhaps the reason was character difference, or more likely, the root of it was money. The way La Borde promised, paid or did not pay others involved in the project, including the music engravers, may have led to precarity and misery — François Moria died penniless. [6] Moreau might have been alarmed at an expansion of the brief (La Borde’s prospectus promised 2 volumes, and 50 songs and illustrations in total, whereas clearly he had expanded his vision to double that size at some point between the prospectus and the project unfolding); Moreau might have had cause to doubt La Borde’s ability to pay, and in demand as he was for a host of other projects, and newly in place as the “Dessinateur des Menus Plaisirs du Roi” after Cochin’s passing, he wisely prioritized steadier, more reliable, and more prestigious work over the notoriously ambitious tax farmer who managed himself to live in financial difficulty and debt despite having what amounted to a license to print money from the Ferme.[7]

All this led to La Borde having to make decisions about who he was going to recruit for the remaining (and much over-promised) volumes to the subscribers. We lack specific archives or correspondence that would confirm how the artists and engravers were chosen, but what we do know is that whereas Moreau was a one-person solution, a peintre-graveur, who could both design and brilliantly etch the plates, there would now need to be a team to replace him.

This team, would be made up of a designer, a trained artist to draw the designs on the basis of the song and create the compositions for the plates; and then these would be handed over to skilled engravers who could interpret and transfer the designs onto the plate and ensure the prints were created according to the relatively specific requirements of the Choix de Chansons.

La Borde might well have been aware of ambitious projects and engraving teams that could have done the job – like the engraving teams around the Martinet Enterprise who were creating an ambitious series of engravings for editions of popular Opéras-Comiques at around the same time. [8] Instead, though, in a sign of his ambition or perhaps of his desire for sufficiently high-prestige replacements for the irreplaceable Moreau to placate the souscripteurs, he alighted on a young generation of painters whose trajectories would not at first sight have made them obvious or natural choices.

The designers he chose were three aspiring history painters, Joseph Barthélemy Le Bouteux (1742-after 1777) who designed all the engravings in volume 2; Jean-Jacques François Le Barbier (or Lebarbier), (1738-1826) who created all the designs for volume 3, and Jacques-Philippe Joseph de Saint Quentin (1738- after 1785) who contributed designs to volume 4. We are fortunate that the drawings that show the designs for all four volumes have survived in the Chantilly copy of the Choix de Chansons and can of course be browsed in our digital critical edition and this essay will link and refer to these comparisons often.

The Engravers who would pick up the complex and heavy work of actually creating the etchings from these designs and translating them to the physically restrained but aesthetically ambitious format of the chansonswere François Denis Née (1732 –1817) and Louis-Joseph Masquelier (sometimes known as Masquelier the Elder) (1741 –1811).

It is fair to say that with the possible exception of Le Barbier, this group of artists is not familiar to many beyond eighteenth-century specialists, and has not been especially well documented in art historical literature. The painter-designers Le Bouteux and Saint Quentin in particular have disappeared into semi-obscurity. Given the relative neglect of engravers’ lives and contributions in Art History generally, it is perhaps not surprising that we do not have copious literature on Masquelier or Née. But it is notable that those that contributed visually to the bulk of the Chansons remain under-known. In what follows I hope to refresh, where possible, our understandings of the artists and their involvement with the project but also to look again at the designs in volumes two three and four, to revisit their work which has always suffered in comparison to the glories of Moreau’s first volume.[9]

The Designers

All three of the painters whom La Borde enlisted in the wake of Moreau’s departure were ambitious young painters, trained in most cases in exclusive and hard-to-get into schools or with the backing of powerful masters and competing for the prized pathway of entry into the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. They were, in their early career stages, eager to climb to the heights of official patronage and gloire, and they were recruited while they were making their way through the Academy ranks or into public consciousness. As a group they constituted a surprising choice for what amounted to a new and experimental kind of illustration project. There was of course precedent for painters at an early stage of their careers being extensively involved with the print trade—Francois Boucher’s involvement with the Receuil Julienne and the is just one such example. And indeed, involvement in ambitious engraving and illustration projects was not at all unfamiliar territory for aspiring and talented painters throughout the eighteenth century. Besides Boucher, Oudry, Coypel, and Fragonard, to name but a few, lent their considerable design skills to prestigious illustration projects in the course of the century and often enhanced their reputations by doing so.

Joseph-Barthélemy Le Bouteux

So who were La Borde’s chosen painters? Firstly, there was Joseph-Barthélemy Le Bouteux, [1744-after 1777] who remains perhaps the most biographically mysterious of the trio of designers.[10] Le Bouteux was a bright young thing, a likely lad—son of an Academician, (Pierre-Michel Le Bouteux, 1683-1750) born in Lille in 1742, he was by the early 1760s both excelling in the Academy school and in the atelier of Noel Hallé. He won the coveted Grand Prix of the academy school in 1769 for his painting Achille, après avoir traîné le cadavre d’Hector, le dépose aux pieds du lit où repose le corps mort de Patrocle now at the ENSBA in Paris, for which a lively study was recently on the private market.

Figure 2, Joseph-Barthélémy Le Bouteux, The death of Patroclus, with the body of Hector brought by Achilles, 38.7 x 50.1cm, black chalk, pen and brown ink, brown and grey wash heightened with white, Art Market. Photo, Christies.

Figure 3 Joseph-Barthélémy Le Bouteux, The death of Patroclus, with the body of Hector brought by Achilles,1769, 110 x 145cm, Oil on Canvas, Paris ESNBA, Depot du Louvre © 2014 Grand Palais Rmn (musée du Louvre) / Agence photo

This coveted prize would bring Le Bouteux the opportunity of a stay in Rome- which he took up in 1771, and where he was a companion and friend of a very talented generation – including Francois-Andre Vincent – to whom we owe this rather marvellous Portrait-Charge of the student now at the Musée Carnavalet.[11]

Figure 4 François-André Vincent, Portrait Charge du peintre Le Bouteux, Red chalk on Paper, 42 x 34.1 cm, 1772, Paris: Musée Carnvalet: Photo Wikimedia Commons

In Rome, as Raux and others have discussed, he developed a skilled drawing practice and applied it not only to studies of art but also to landscape.

Figure 5 Joseph Barthélémy le Bouteux, Vue animée de Caprarola (c.1774, Sanguine 38,5 x 30,5cm Paris Art Market)

it was indeed while he was in Italy that he took on the project of the designs for the second volume—and this of course raises the question of how he came to La Borde’s attention. This mystery is solved however because we know that La Borde found him in Rome. Careful attention to the correspondence of Natoire, the then Director of the French School in Rome, reveals that Jean-Benjamin de La Borde was out in Rome in 1773, was staying in or around the French Academy, and returned to France somewhere after 15 September that year. [12] Perhaps the fluent, graceful landscape drawings of the young student convinced La Borde that Le Bouteux could fill Moreau’s shoes for his purposes. It is in any case very likely that this Rome meeting is the reason for Le Bouteux’s enlistment to the project, and the obviously cordial relations between La Borde and the Academy hierarchy demonstrated in his appearance in this correspondence points to a network which may have allowed him to enlist other talented young Academy pupils . We know from the Frontispiece dedicated to the Dauphine in Vol 2 that Le Bouteux’s design is signed “Le Bouteux Inv Delin Romae 1774”, so we know he continued to send designs for the engravings for volume 2 from Rome.[13]

It was a tall order, of course, to live up to Moreau’s mastery of the visual registers and idioms that would lend variety, humour, and energy to his illustrations for the first volume. And where Le Bouteux tries to compete too directly on Moreau’s territory, (for example in “L’HYVER”, CDC II, no 4) there is a perhaps inevitable comparative ungainliness. However, I believe former judgements of the volume underestimate the liveliness and humour of Le Bouteux’s drawings (preserved in the Chantilly copy).

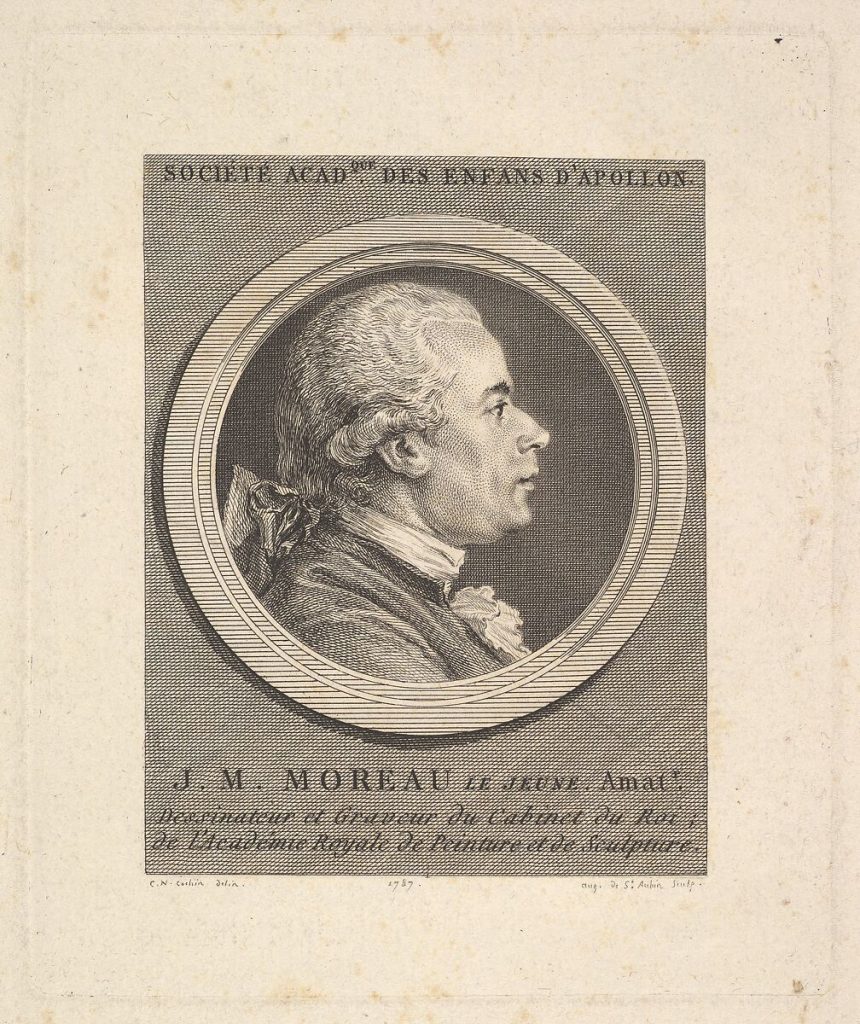

(Firstly, we see how his experience in Rome makes him attentive to the architectural and spatial possibilities offered by such songsets as L’Enlèvement (CDC vol 2, no 58), in which by the light of a moon and a fire we see the escape from a convent of a young woman, the action set against an amalgam of sculptural and architectural detail

Figure 6 Le Bouteux, drawing for L’Enlevement, Choix de Chansons, Chantilly copy, S.2.10.

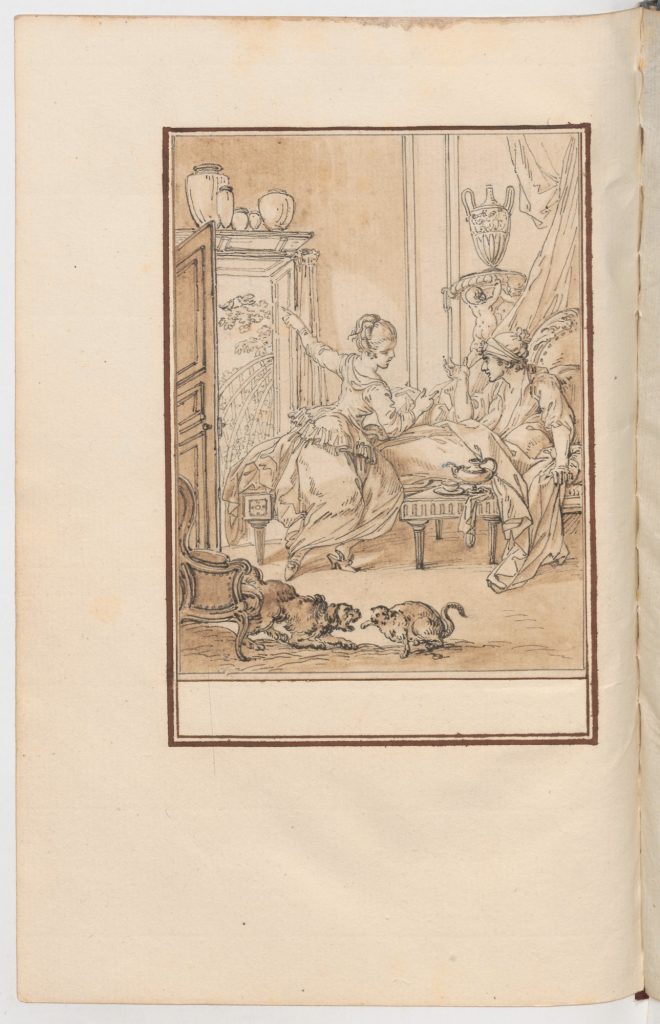

Or again, in Le Clavecin, (CDC II, no 7), the elegance of the young lady’s salon in which the suitor is smuggled in the Harpsichord is noteworthy for its early neo-classical (rather than rococo/pastoral) taste and furnishings, conveyed elegantly through architectural and furniture details, and the scene is enlivened by borrowings from the Greuzian repertoire of deceptions and furious entrances, pointing to a knowing ‘update’ to the aesthetic of the Choix de Chansons.

Figure 7: Le Bouteux, drawing for Le Clavecin, Choix de Chansons, (Chantilly copy), S.2.07.

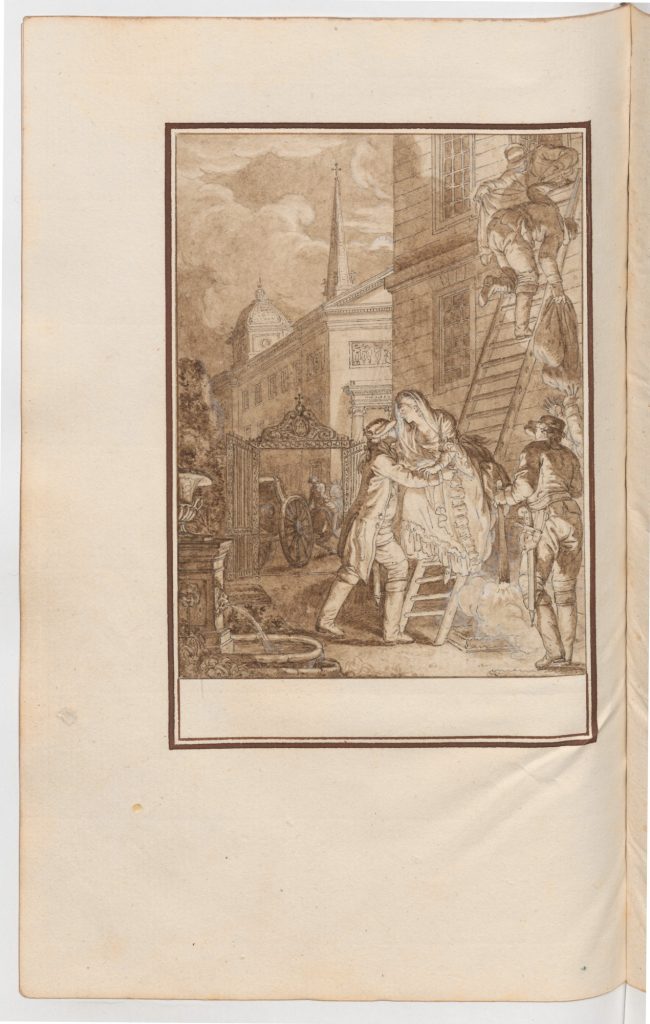

In the very opening design of volume 2, for, Printemps, ou la volière (CDC II, no 1) It is not too fanciful to see in the modelling of the dense flora, the rendering of the statue-strewn garden spaces and even the architecture a hint of the fashionable renderings of Rome and its surrounds that Le Bouteux had come to be known for as well as a more contemporary elegance in the poses and costumes and a nod to new forms of informal garden design.

Figure 8: Le Bouteux, drawing for Le printems ou la volière, Choix de Chansons, Chantilly copy, S.2.01.

Even his attempts here and through the course of the 25 designs of Volume 2 to capture the sometimes-comic animal life of the Chansons owes something to Le Bouteux’s obvious talent for animal depiction, developed during his Roman sojourn

Figure 9 Le Bouteux, Head of a cat, Counterproof of a red chalk drawing, (c.1774, Besancon, Bibliothèque Municipale, P-A Paris Collection)

Le Bouteux’s fertile sojourn in Rome, designed as a prelude to a glorious career, was in fact the last moment of his visibility, and historians lose contact with him after his return from Rome in 1775 (we presume, though we have no specific documentation of any precise departure or return date). He was present at the Academy in 1776 for one session, and I believe that perhaps he might be the Barthelemy-Joseph Le Bouteux who married in Paris in 1777, but I can as yet find no further trace of him –and this disappearance is somewhat surprising in its completeness. One suspects that Le Bouteux’s life was cut short somewhat prematurely– but the lack of notice of his death is a puzzle, as is the complete lack of evidence of work after the 1770s.[14]Certainly he never presented a provisional or full acceptance piece to the Academy, (which would have been the logical and expected step for a painter of his promise). So the Choix de Chansons designs and engravings are in fact Le Bouteux’s most sustained artistic work.

Jacques-Philippe [de] Saint Quentin

Another up-and-coming artist and Rome Prize winner who was brought into the project and worked on the fourth volume was Jacques Philippe Joseph (de) Saint Quentin, another former pupil of the feeder schools to the Academy, and an artist of ambition who had won the Grand Prix in 1762, on the strength of his Death of Socrates.[15]

Figure 10 : Jacques-Philippe Joseph de Saint Quentin, The Death of Socrates (1762, Oil on Canvas, Paris: ENSBA)

For pecuniary reasons, it seems, he had to wait a good couple of years for the actual voyage to Rome, while designing engravings for a number of publications including the second volume of Puget’s Nouveau Receuil de Parures de Joyaillerie in 1764.[16] His Brevet as a pensionnaire to travel was issued in 1765.[17] He arrived in Rome in September 1765[18] and departed for Paris again slightly early in 1769.[19] His sojourn in Rome doesn’t seem to have been an unalloyed success, if we can trust the administrative traces of the Correspondance des Directeurs.[20] He then seems to have encountered further difficulties on return to Paris, and while he continued to produce drawings and other designs and accomplished drawings in Boucher’s manner. After Boucher’s death in 1770, he seems to have made an attempt to establish himself as an academician, according at least to the most notorious ‘resurfacing’ of the artist’s name in the early 1770s, famously fictionalized by Denis Diderot as the acerbic and viciously opinionated interlocutor “Saint Quentin” of the Salon de 1775, a salon critique in the form of a dialogue explored expertly by Bernadette Fort.[21]According to Diderot’s account, “ he had presented three or four paintings in a row to the Academy for his provisional membership and they had all been rejected.”[22] And although the traces of these unsuccessful attempts are rather surprisingly not visible in the Academy minutes, (perhaps because the Academy prefer not to note unsuccessful presentations for agréments, unless in exceptional circumstances), it is perfectly plausible that this is the case; this means that at the very moment Saint Quentin was creating the designs for the Choix de Chansons he was attempting to become a member of the Academy. Perhaps he saw in La Borde’s patronage a useful tool in the network, especially given the death of his former master and protector, François Boucher. The fact that he was rejected by the Academy might also explain why he would eventually exhibit in the short-lived rival exhibition at the Colisée in 1776. His contribution to that exhibition was actually both surprisingly large and diverse in media, including several works in Camaïeu Bleu, the monochrome blue technique used by Pillement and others.[23] So, we can assume that the work for the Chansons was part of his campaign to get himself both noticed and commercially on a decent footing as an artist of flexibility and design talent in the wake of his lack of success with the Academy. The motivation for Saint Quentin to be part of the Chansons project might also have been financial—because, as Courajod notes in his history of theEcole Royale des Elèves Protégés, the school at which Saint Quentin had succeeded was also in deep financial trouble and didn’t pay the promised grants to the students resulting in Saint Quentin’s contracting debts and creating his own system of IOU’s on the promised payment.[24] Saint Quentin cleared these debts, suddenly and all at once, in 1774. It has been assumed that these debts were finally acquitted by the Crown, but it might also be that Saint Quentin actually got paid by La Borde for his contributions to the Choix de Chansons and used his payment to close his debts.

Saint Quentin’s contributions to the Choix de Chansons then, fit into a complex and we must presume somewhat frustrated life as an aspiring but failing academician. Indeed we know that following the exhibition at the Colisée, the artist made a move away from Paris and found himself in the service of a far more commercial and less prestigious operation, in Colmar in Alsace, working as part of a large group of painters from various communities making designs for the commercial enterprises of a wallpaper and printed fabric manufacture set up by Jean Michel Haussman, great uncle of the more famous Baron.[25] In Alsace, it seems, Saint Quentin became an active member of literary and other societies including the Tabagie littéraire, associated with the poet and salonnier Théophile-Conrad Pfeffel .[26] Given his work for Le Mariage de Figaro, (See below) we must presume he returned from Alsace to Paris sometime in the mid 1780s, but we lose track of Saint Quentin and his work after the 1780s, and like Le Bouteux, we have no certain archival trace of any marriage, or his date of death.

Saint Quentin was responsible for only 7 of the 25 designs in volume 4 of the Choix de Chansons. These are (with hyperlinks to the Digital project) S.4.07 Le danger de se deffendre, S.4.12 Dame françoise, S.4.14 La bagatelle, S.4.15 L’heureux songe, S.4.17 Le sommeil de l’amour, S.4.18 L’amour vainqueur de la raison, S.4.03 Les vendanges de Cythere

Saint Quentin’s contributions are of a lively, ludic tone, demonstrating his grasp of the comic and erotic underpinnings of many of the songs – in 4.14, La Bagatelle, in which the song tells of a young bride married to an older man who vainly attempts to remind her husband of the joys of physical love by pointing to the mating sparrows outside, and is spurned as flighty and superficial. The game of contrasts, in décor, body, even cat and dog in eternal conflict in the foreground, the young lady’s hopeful gesture towards the outside and its freedoms and desires, is a comic improvisation on the themes of the short ‘chanson’ it partners.

Figure 11: J-P de Saint Quentin, drawing for La Bagatelle, Choix de Chansons, Chantilly Copy, S.4.14.

Saint Quentin’s visual inventiveness is also evidenced in his response to the ‘dream’ narrative of 4.15, l’heureux Songe in which he figures the dream via a vaporous vision of a sleeping young man, an unusual enough composition to have attracted some scholarly attention recently. [27]

Figure 12: J-P de Saint Quentin, drawing for L’Heureux Songe, Choix de Chansons, Chantilly Copy, S.4.15.

One of the other lively, comic toned songsets that Saint Quentin created images for was 4.12, La Dame Françoise which I will illustrate with the Chantilly drawing; The lively and loose creation of ducks and animals, rustic detail, etc., is a response to a chanson, “A dieu donc la dame Françoise”, which itself is a gentle re-worked parody of the famous Epigram attributed to Racine and Boileau on the failure of Fontenelle’s Aspare,

Adieu, ville peu courtoise,

Où je crus être adoré.

Aspar est désespéré.

Le poulailler de Pontoise

Me doit ramener demain

Voir ma famille bourgeoise,

Me doit ramener demain,

Un bâton blanc à la main [28]

Figure 13: J-P de Saint Quentin, drawing for Dame Françoise, Choix de Chansons, Chantilly Copy, S.4.12.

This is clearly the source of a parodic song which Saint Quentin captures in its comic tone and enjoys the rustic comedown of the dismissed lover and the paraphernalia of the chook-transporting market wagon. There is an irony though that this song dwelling on a frustrated and ignominious departure, based on an episode of artistic failure, plotted a course for the designer himself, who would leave Paris for province and commercial employment in the wake of his lack of academic success.

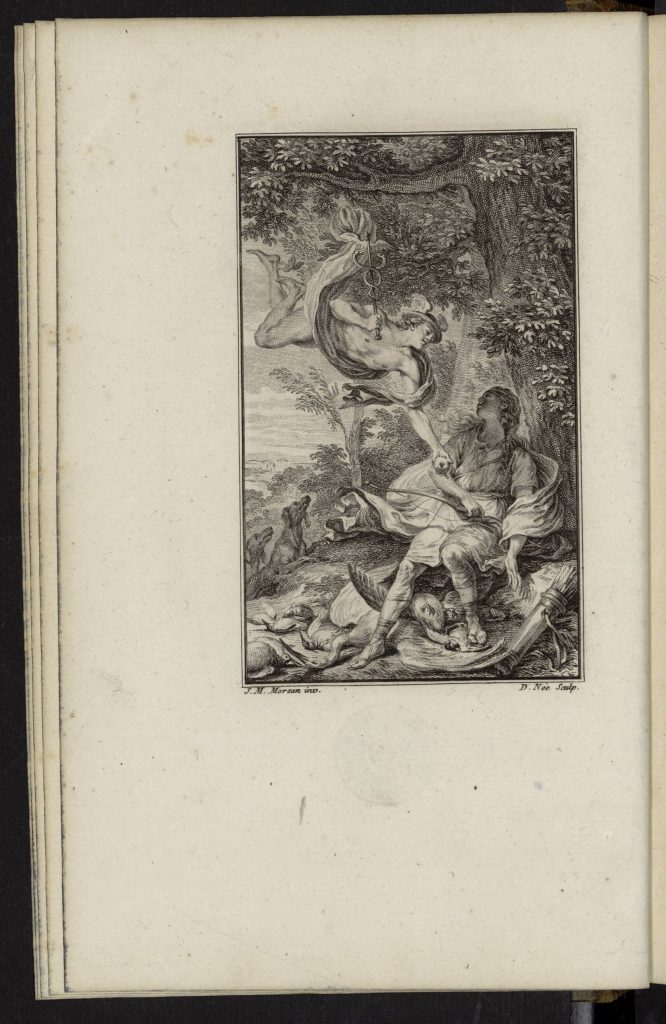

Another of Saint Quentin’s contributions foregrounds his practice and experience with explicitly eroticized imagery, S.4.18 L’amour vainqueur de la raison where he takes the song’s renunciation of reason for passion and love in sculptural and explicitly erotic directions in his juxtaposing of a toppled statue of a demure maiden of reason (leaving only the shoes on the plinth) with the carnal approach of the naked young woman to the statue of Amour, all set in a somewhat improbably neo-classical salon.

Figure 14: J-P de Saint Quentin, L’amour vainqueur de la raison, Choix de Chansons, Chantilly Copy, S.4.18.

Saint Quentin’s single most public contribution in the 1770s immediately after the publication of the Chansons was his somewhat clumsy print dedicated to the newly crowned Louis XVI and his queen, Marie Antoinette, Les Garants de la félicité publique (1774) for which his design survives in the BNF. Some of the energy of the Choix de Chansons designs permeates this allegory but its odd perspectives and lack of total coherence as a design perhaps point to the problems Saint Quentin encountered tackling the noblest themes and allegories expected of a history painter. The finished engraving, was published with a flourish of a dedication to the King in 1774 by the same team that worked on the Chansons, (Nee and Masquelier) and it seems to me that this allegory was a response, perhaps encouraged by La Borde himself, to the transition to Louis XVI which actually, for La Borde, wasn’t a guarantee of his own felicity, given his closeness to the regime of Louis XV.

Figure 15: J-P de Saint Quentin, Les Garants de la Félicité, Black chalk and red chalk, c.1775, Paris, BNF.

Figure 16: Née and Masquelier, after Saint Quentin, Les Garants de la Félicité Publique, Etching and Engraving, 1775, Paris: BNF.

Where the allegory perhaps showed Saint Quentin as a less secure draftsman than either Moreau or Le Bouteux, his spirit and comic talent is obvious in the limited amount of illustrations he created for the Choix de Chansons. We are aware of his and indeed, that comic talent was even more evident in the spectacular return to public notice enjoyed briefly by Saint Quentin in the mid 1780s, in the form of his contributions to an illustrated edition of the wildly popular play by Beaumarchais, Le Mariage de Figaro. Saint Quentin’s illustrations have become familiar to all those interested in this epoch-making drama

Figure 17: Claude Nicolas Malapeau after J-P de Saint Quentin, Illustration for Act IV of Le Mariage de Figaro (Etching and Engraving, 1784, New York, Metropolitan Museum)

We should only note here though that the composition and details of these illustrations for Beaumarchais’ drama are indebted to the decors, costumes and gestures of Saint Quentin’s Chansons work, (in contradiction to the actual visual vocabulary of the play’s stage directions which ask for a much more markedly retrograde ‘espagnole’ style). We should also note that, decades after his return from Rome, and perhaps bitterly, the illustration to act IV bears a legend making it clear that Saint Quentin was conscious of the importance of having once been a ‘Prix de Rome’ winner and pensionnaire- he signs the print ‘Dessin par Saint Quentin Ancien Pensionnaire du Roi’.

After 1785, scholarship again loses track of Saint Quentin, which is again surprising, but we can hope that archival research might finally chronicle his fate after 1785.

Jean-Jacques François Le Barbier

Le Bouteux, most probably, died prematurely, Saint Quentin never had the career he had hoped for, and seems also to have died in obscurity, but the artist who contributed the single largest amount of designs to the Chansons project as a whole did go on to a more distinguished and better chronicled career.

Jean-Jacques François Le Barbier, or Lebarbier, (1738-1826), supplied 53 designs to the project, across volume 3 (which he entirely created) and volume 4, for which he supplied 18 of the 25 designs.

Figure 18 Jacques-Antoine-Marie Lemoine, Profile Portrait of Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier, Black and red chalk, and watercolor on cream antique laid paper, laid down, framing lines in black ink, c. 1775? Harvard Art Museums.

Le Barbier, perhaps, is the most evidently talented of the three artist designers who took over from Moreau, and the artist would continue to juggle a career as a history painter with extensive involvement in design and illustration projects, in particular being closely associated with La Borde in other projects, including the equally ambitious and financially fraught collaboration between La Borde and Beat Fidel Zurlauben (1720-1799) the“Tableaux de la Suisse” (1780-6), again working with Née and Masquelier, among others.

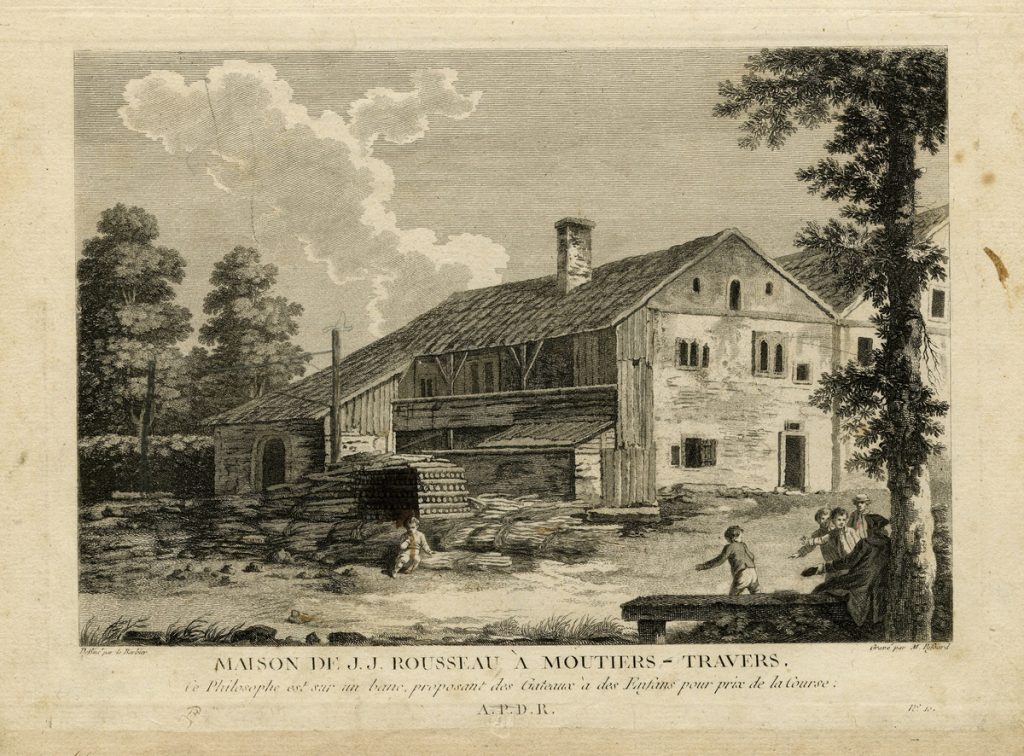

Figure 19: Etienne Fessard after JJF Le Barbier, Maison de J-J Rousseau A Moutiers-Travers (from Tableaux de la Suisse), 1780-86, Geneva, Municipal Library.

Perhaps more importantly for his career, Le Barbier also embarked after the Chansons upon a set of engravings illustrating the fable-like moral tales of Salomon Gessner, whose enormous popularity is now forgotten but who was a sensation in later eighteenth-century Europe. Le Barbier seems to have made a special effort not just to understand and transmit Gessner’s morals and sentiment in an ambitious project inspired by his encounter with Gessner’s work, but to publicize and use his personal engagement with Gessner to bring his work to the attention of authorities, and help get the edition published. This is visible in the minutes of the French Royal Academy of Painting, where we note a number of exchanges between Le Barbier and the academy. Firstly, on 29 April 1780, the Academy note receiving a letter from Le Barbier announcing and sending an advanced copy of volume 1 of his edition [29]; gifts of further volumes would arrive regularly thereafter, although the edition was not finally published until 1786, and on completion became a posthumous edition as Gessner died in 1788.[30] But perhaps more significantly, the gift and the project seemed to have propelled Le Barbier up the pecking order. Only a couple of months after the initial letter and gift, Le Barbier, who, unlike Saint Quentin and Le Bouteux, was not a Grand Prix winner, was presented for and achieved provisional membership of the Academy. [31] His academic career began then, and he pursued a career as a History painter alongside his work for various design and illustration projects. So it might be said that while for Le Bouteux and Saint Quentin, the Chansons marked a high point, for Le Barbier the project was more of a launching pad, and even something he needed to ‘counter’ through a much more serious-toned and morally tuned project for the Gessner engravings.

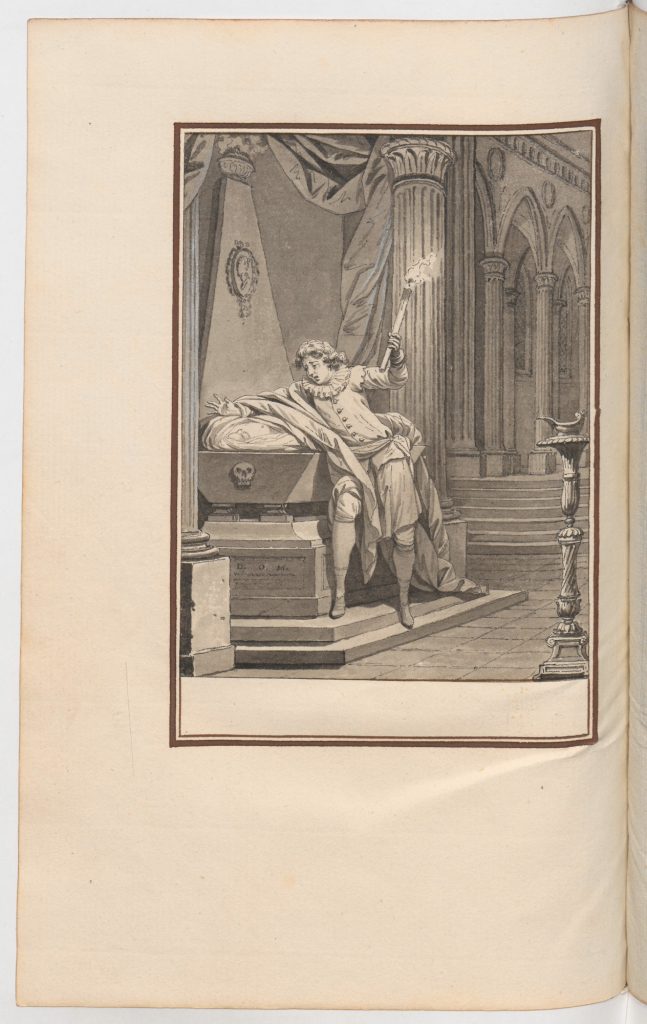

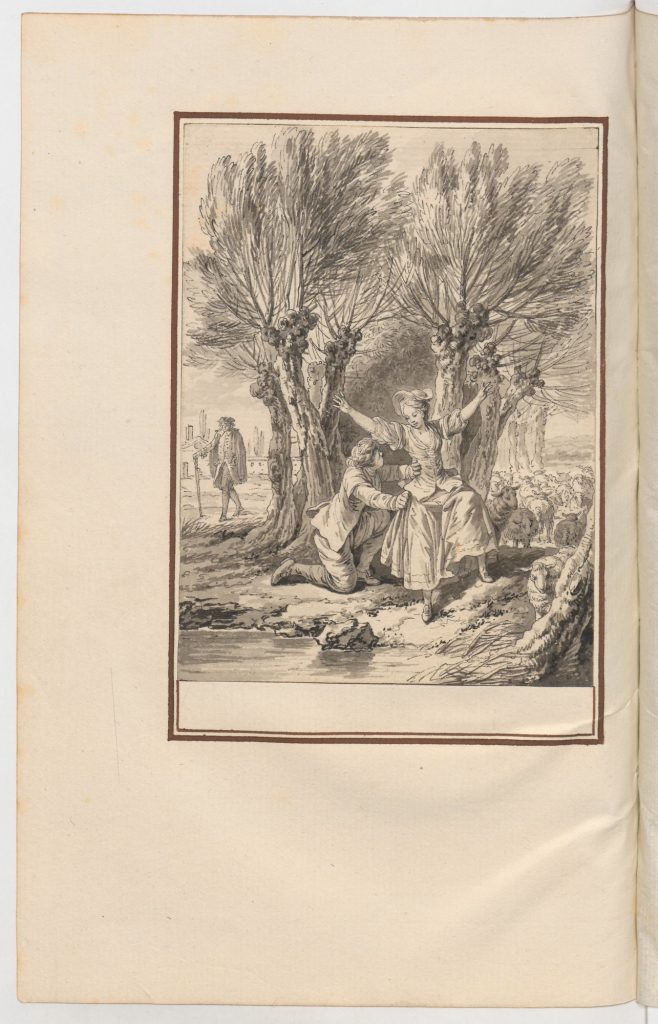

Across the we are witness to his fluency and familiarity in a variety of idioms, tones and styles. Certainly, his work demonstrates a painter’s knowledge of various historicizing as well as pastoral and classicizing idioms. Take for example his interpretation of the slightly strange song 3.19, where his familiarity with the ‘medievalizing’ trend of the 1770s as well as the sepulchral architecture, etc, shows him to be an artist transitioning away from the World of Boucher but in tune with painting’s current fashions.

Figure 20: Jean-Jacques François Le Barbier, Le Regrets de Petrarque, Choix de Chansons, Chantilly Copy, S.3.19.

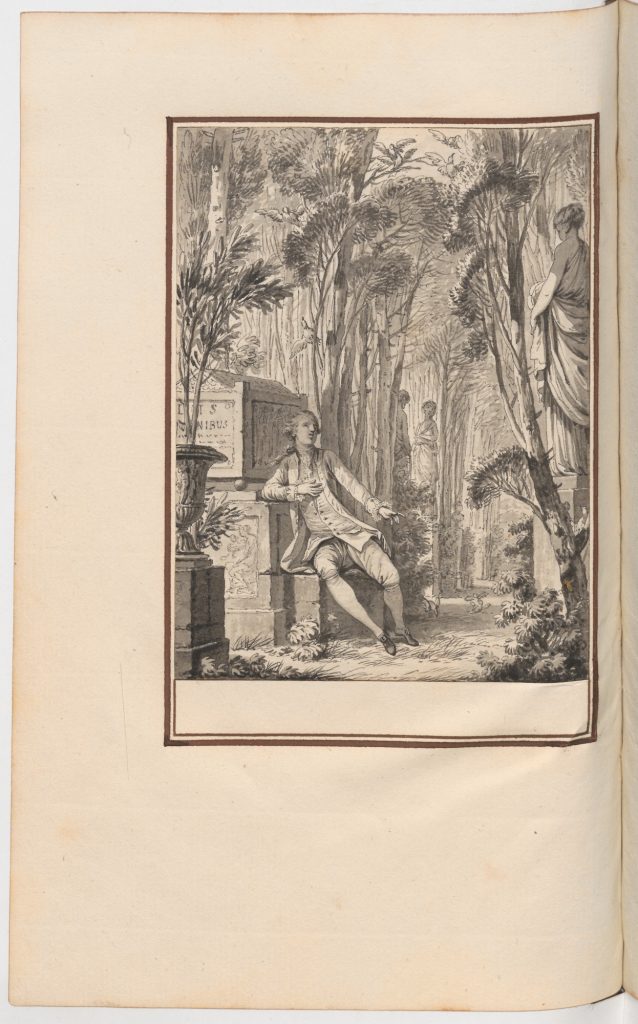

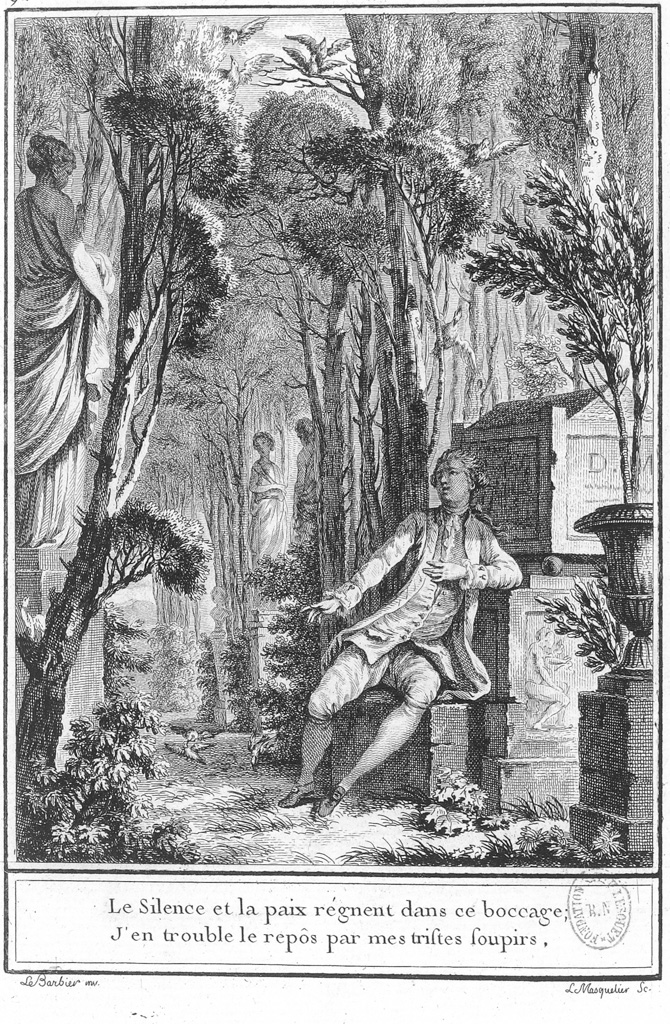

And in 3.16, Le Berger amoureux this tendency is even more deeply entrenched – his pining shepherd is more like an antiquarian or grand tourist, suffering among the statues of a formal garden rather than in a Boucher-like bosquet.

Figure 21: J-J-F Le Barbier, drawing for Le Barbier Amoureux, 3.16, Choix de Chansons, Chantilly Copy

Figure 22 Masquelier after Le Barbier, Le Berger Amoureux, Choix de Chansons, S.3.16

Other designs echo the grandeur and formality of this setting and feature elegant and well-dressed characters in delicate and polite relations – for example 3.15 La Vengeance Impossible However in other designs like that for he shows more acuity for the older pastoral and pseudo-pastoral imagery, picking up perhaps on the salacious humour of the song itself.

Figure 23: Le Barbier, drawing for Le danger de tomber, Choix de Chansons, Chantilly copy, S.4.21.

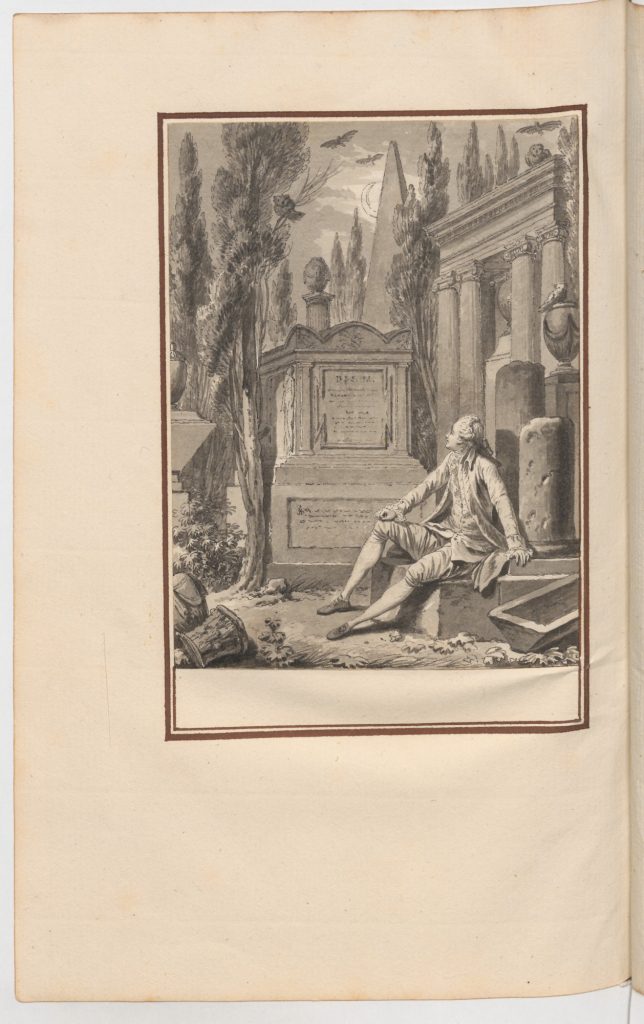

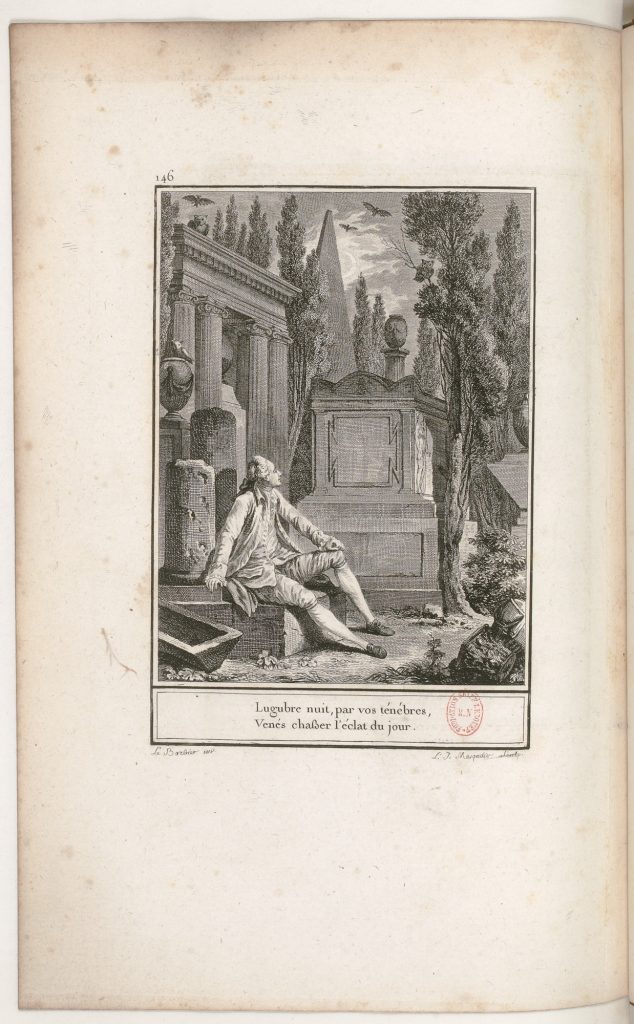

And again, in other songsets we see a different register and tone, like the striking pre-Romantic moonlit contemplation and architectural ensemble of S3.15, Le Mélancolique

Figure 24: J-J-F Le Barbier, drawing for Le Melancolique, Choix de Chansons, Chantilly copy, S.3.25.

Figure 25 Masquelier after Le Barbier, Le Melancolique, Choix de Chansons, S.3.25.

Le Barbier, while lacking the deftness of Moreau was clearly an artist of fecundity, variety and energy, and this energy and nimbleness across registers would translate later into his career as a history painter.

his reception piece at the Academy in 1785 would be a seduction narrative with deep implications- Juno’s hypnotic seduction of Jupiter on Mount Ida.

Figure 26 Jean-Jacques Francois Le Barbier, Jupiter endormi sur le Mont Ida. 1785,Oil on Canvas, Paris, ENSBA.

However, only a matter of a few years later, he would be fully embracing a new and much sterner idiom made current by David and his pupils in the mid 1780s, and indeed Le Barbier took up the theme of the Horaces in a couple of paintings in 1787 that we know from prints or recent resurfacings.

Figure 27: J-J Avril after JJF Le Barbier, Le Combat des Horaces…ou le Dévouement pour la Patrie, 1787, Geneva, Musée d’art et histoire.

A recently resurfaced painting in this series, sold for multiple of its estimate at Christies was his 1791 Salon entry, The Magnanimity of Lycurgus which demonstrates clearly the transformation of the painterly style of Le Barbier in the light of new aesthetic and social priorities.

Figure 28: JJF Le Barbier, The Magnanimity of Lycurgus, 1791, oil on Canvas, Art Market: Photo, Christies.

Le Barbier, in fact, had become enthused by Revolutionary politics in the years after 1789, and this painting became part of a print project opposite in tone and substance to the Choix de Chansons. The printmaker and publisher Jean-Jacques Avril seems to have owned the Lycurgus and published a suite of prints after it and other works of Le Barbier, designed to highlight patriotic and Revolutionary virtues. However, undoubtedly Le Barbier’s most striking contribution to these Revolutionary years was his painted design for the text of the Declaration of the Rights of Man, created in the wake of the extraordinary sessions of August 1789 and then printed by Laurent and still recognizable today across prints and other visual media. [32]

Figure 29: J-J F. Le Barbier, Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, 1789, Oil on wood panel, Paris: Musée Carnavalet.

Le Barbier became involved in the circle of the ‘reformists’ in the dying years of the Académie Royale and then in the projects of Jacques-Louis David for the renovation or replacement of the Academy during the high Republican moments of the Revolution, but after the winds changed post Thermidor, Le Barbier continued to contribute to the Paris Salon, and to produce ambitious illustrations, including those for the translation of Thompson’s Seasons in 1795. [33] Later under the empire Le Barbier got involved once again in ambitious illustration and design projects, most notably the ambitious publication of the works of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, published by Gay in Paris in 1806. Le Barbier’s drawings for this project survive and are currently at the Morgan Library. [34]

For Le Barbier then, the Choix de Chansons really did provide one important springboard to a career in which the business of design for illustration remained entirely compatible with a career in the noblest genre of painting, and we might him as one of the few creatives involved with the project who emerged unscathed and enhanced by the Choix de Chansons in the decades that followed.

The Engravers: Masquelier and Née

In that category too belong the two most prolific ‘workhorses’ of the project whose signature (along with that of Moria and Mlle Vendome) is most evident all across the Choix de Chansons. These are the engravers Francois Denis Née (1732 –1817) and Louis-Joseph Masquelier, (the Elder), 1741 – 1811.

Née and Masquelier were contemporaries and fellow ‘students’ in the probably the single most influential print-shop of the mid-eighteenth century, that of Jacques Le Bas. [35] Indeed in Masquelier’s case Le Bas was happy to co-sign engravings with him in the early 1770s, notably engravings after Flemish and Dutch landscapes (fig.)

Figure 30: Jacques Le Bas and Louis Joseph Masquelier after Ruisdael, Landscape, Etching and Engraving, 1772, London, British Museum.

Née, too, participated in these and other major projects of the Le Bas print shop, including complex and prestigious projects like Les Conquêtes de l’empereur de la Chine which involved complex diplomatic as well as aesthetic challenges. [36] Clearly adaptable, rapid-working and competent, Masquelier and Née clearly went into business together, (perhaps as a result of their collaboration on the Choix de Chansons, as we note on the legend of their celebratory allegorical engraving after Monnet on the new reign of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, that they are already established in business at “à “Rue des francs-bourgeois Saint Michel”. This is also made clear by the Prospectus for Laborde’s Tableaux de la Suisse in 1777 which mentions their joint premises on the Rue des Francs-bourgeois Saint Michel (now the Rue Monsieur le Prince) and makes clear that they were jointly responsible for the administration of the Tableaux de la Suisse, as well as the choosing of proofs for subscribers, etc.[37] Before working together for La Borde, they had worked on a number of projects together including contributions to the ambitious edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in Latin and French published between 1767 and 1771, in which Moreau also took part and which might have drawn them to the attention of La Borde as substitutes for Moreau the engraver. [38]Although they were to an extent a double act, they do not co-sign engravings (unlike Mlle Vendome and Moria, for example) and it is clear that they were individually both deft and adaptable engravers of some great skill in their own right, and thus it is worth dwelling on their contributions and careers as individual engravers.

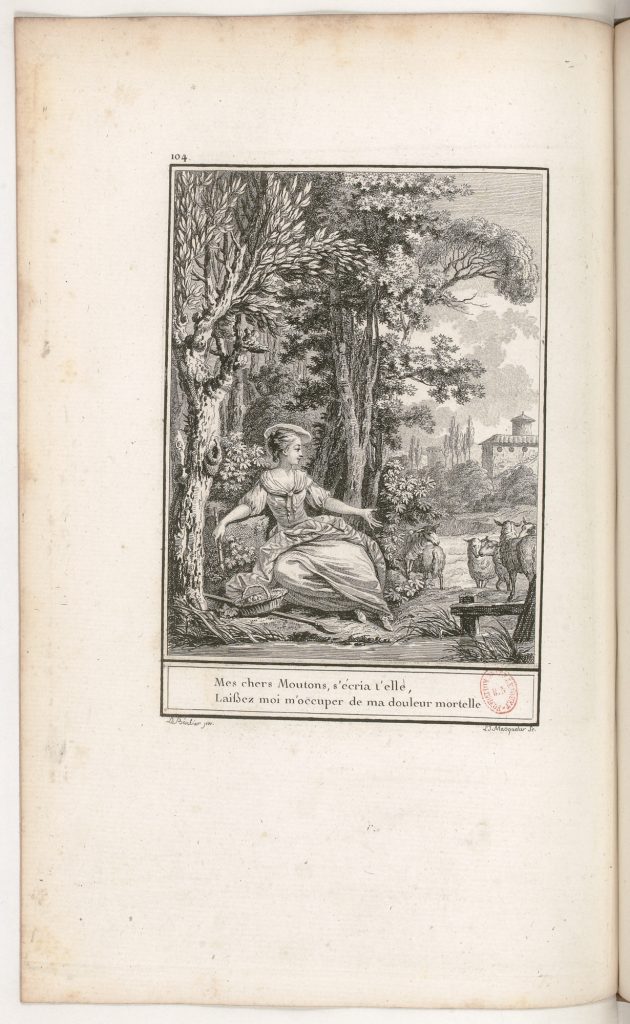

Masquelier, in particular, had shown his flair for ‘erotica’ (or perhaps his lack of fear of taking on such material) in his very successful collaboration with Charles Eisen (and many other engravers) to produce the engravings for Dorat’s Les Baisers. [39] This gift for the subtle innuendo and not-so subtle erotic overtone translated into visual form via the language of the burin is clearly an advantage in Masquelier’s ability to capture with the Burin the comedy and energy of the designs of the artists in what was a rapid-turn around situation in the 39 engravings he created is notable. He is fluent across genres and enhances and develops the designs—see for example his treatment of the floral décor and dress of the heroine of S3.18, La Douleur de l’absence that develops le Barbier’s plainer design.

Figure 31: L-J Masquelier after Le Barbier, La douleur de l’absence, Choix de Chansons. S.3.18.

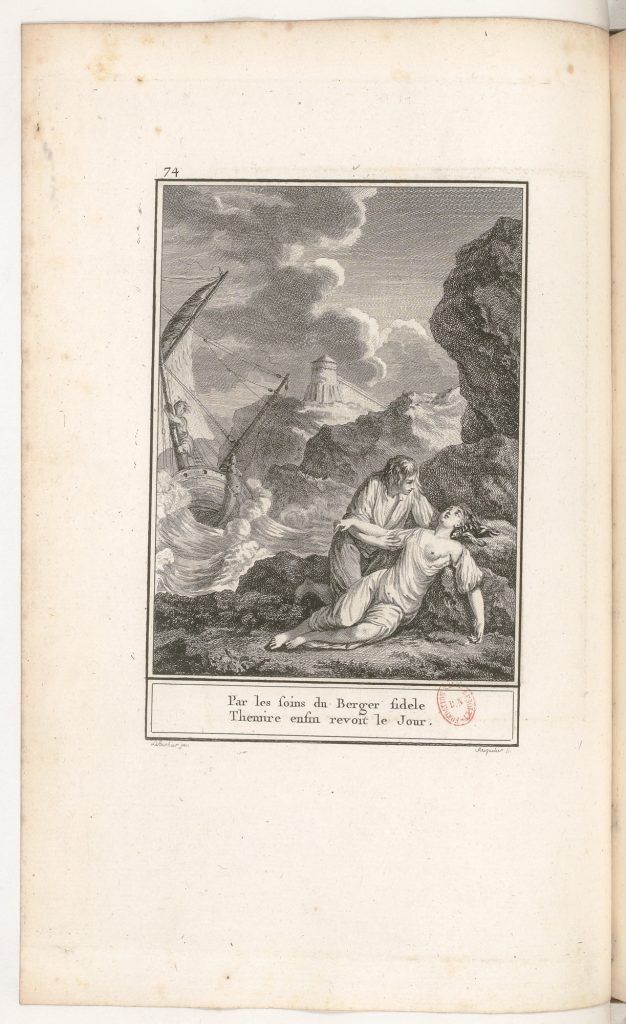

Or again, his dramatic darkening and use of etching techniques to enhance the drama of sea and sky in S.4.13, l’heureux naufrage.

Figure 32: L-J. Masquelier after Le Barbier, L’Heureux Naufrage, Choix de Chansons, S.4.13.

And his response to Saint Quentin’s lively grapple in S.4.07 Le danger de se deffendre creates a darkened sky and increases the dynamism of the plate. In all theses subtle ways, Masquelier proves an ingenious interpreter and often improver of the designs he received for the Choix de Chansons.

Masquelier would remain in great demand as an engraver and illustrator in the years that followed the Choix de Chansons. In particular, and as we can predict from his ease with the shipwreck scene in l’heureux nauvrage and imitation of wash-like techniques in Le Danger de se deffendre, Masquelier became well- known for capturing the drama of the currently fashionable Vernet idiom of shipwrecks through subtle use of etching and engraving techniques to imitate wash and other painterly techniques.

Figure 33: Louis Joseph Masquelier after Claude Joseph Vernet, Le Debris du Naufrage, c.1778, New York, Metropolitan Museum.

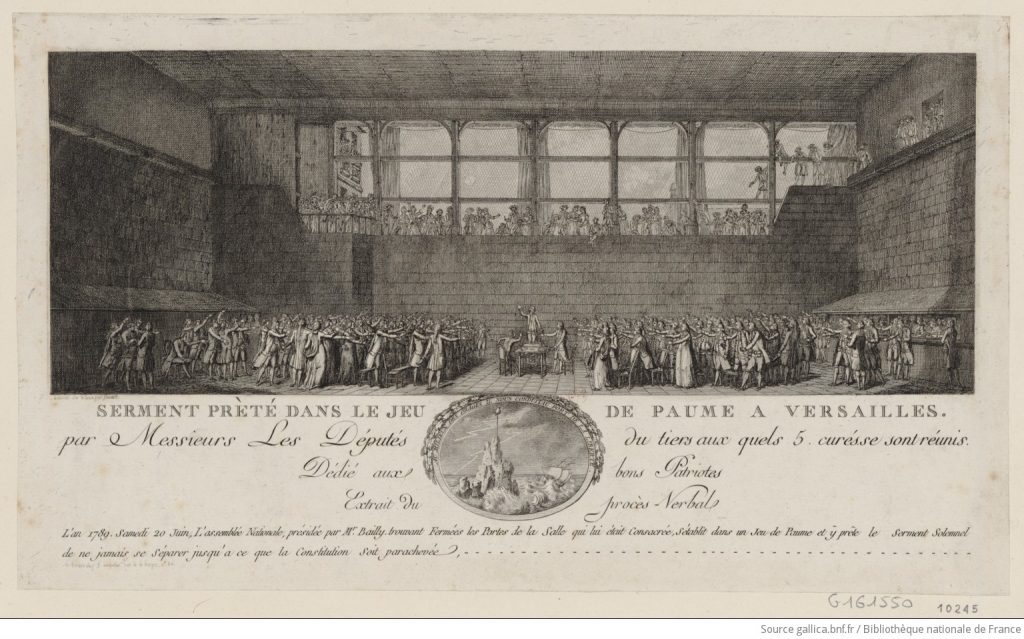

Although he would cooperate with Saint Quentin once again on headpieces and other work including the author portrait for a very luxurious edition of Pierre-Fulcrand de Rosset’s L’Agriculture (1774-82), and other high-luxe products, Masquelier, Like Le Barbier, seems to have been drawn away on the political tide later in the century from the luxuries of the Fermiers-Généraux and the celebration of the qualities of Louis XVI and his court, and towards sympathy with the cause of the Revolution in the 1780s. Indeed one of his most striking works of this period is his engraving after Flouest’s eyewitness design of the Serment du Jeu de Paume in the Tennis Court at Versailles—his is one of the more detailed and rapid chronicles of the events of 20 June 1789.

Figure 34 Marie-Joseph Flouest after L. J. Masquelier, Serment preté dans le Jeu de Paume à Versailles: par Messieurs les députés du Tiers aux quels 5 curés se sont réunis, dédié aux bons patriotes, estampe, dessiné sur le lieux par Flouest, grav. par Masquelier, etching and Engraving, c.1789, BNF: Gallica.

Masquelier would continue to be engaged in printing scenes from the lives of Revolutionary government, as testified by a rare drawing survival, his sketch of the Legislative Assembly on the 10th August 1792 now at the Carnavalet Museum.

Masquelier and his enterprise with Née survived the Revolution, and he then worked in service of the Consulate and Empire. Le Barbier, returned to literary works relatively late in life in a series of illustrations to the edition of Racine’s works produced in 1808 with new commentaries by the critic Julien Louis Geoffroy, as the publishing industry recovered from the market losses of the Revolution and the Didot firm and others embarked on ambitious publication projects. [40]

François-Denis Née’s copious illustrative endeavours likewise deserve more attention than has been granted him, and his skill too as a burin engraver and entrepreneur is equally uncharted in the literature. He, like Masquelier, had been involved in ambitious literary and dramatic illustration projects, most notably working with Moreau, Masquelier and others on the very elegant prints included in Antoine Bret’s ambitious new edition of Molière’s works. [41] He had also been a fluent and effective interpreter of Moreau’s designs for Imbert’s Le Jugement de Paris, in 1772. [42]

Figure 35: François-Denis Née after Moreau le Jeune, Illustration for Imbert, Le Jugement de Paris, Chant 1, etching and engraving 1772: Paris, BNF.

Née was the perfect partner for Masquelier in the creation of the engravings- his experience with specific formats and with illustration projects meant he had a clear understanding of how to make the engravings as impactful as possible in their relatively restrained format. Née engraved 36 of the plates for volumes 2-4, (an almost equal split with Masquelier of the 75 plates in the three final volumes) and focusing on a few will demonstrate a range of his talents as an interpreter.

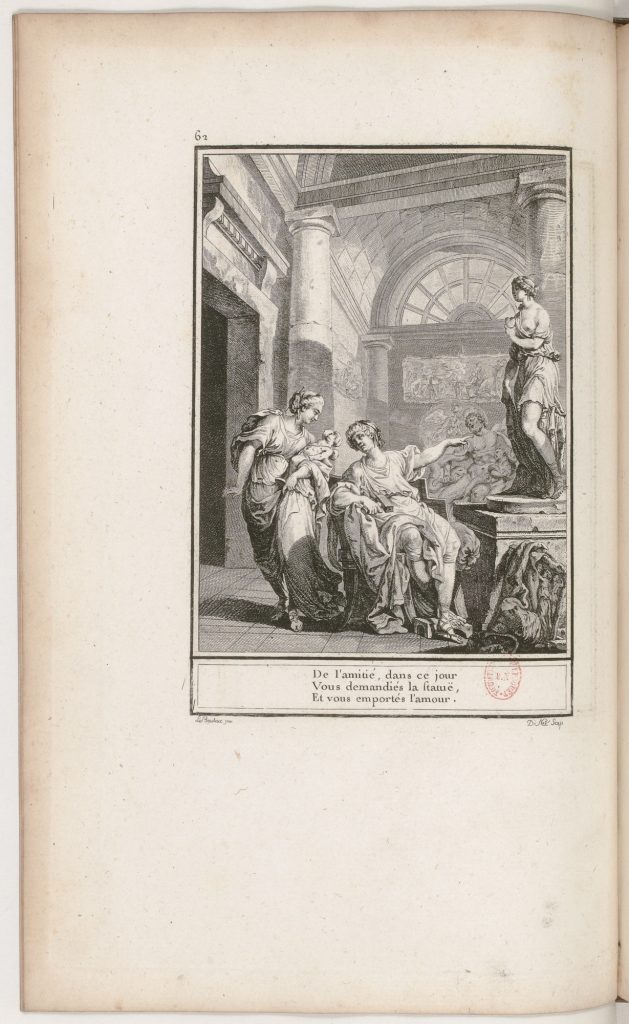

In 2.11 La Statue de l’Amitié, he puts his skill with dynamic and fluid representations of drapery to good work in interpreting Le Bouteux’s design, and even corrects or improves perspective as he responds to the song’s play of humans and statues, friendship and love.

Figure 36 F-D. Née after Le Bouteux, La Statue de l’amitié, Choix de Chansons, S.2.11

And again, with subtle adjustments to the size and perspective of figures, as well as lively capturing of the pastoral setting, Née assures balance and humour in his interpretation of Le Barbier’s design for S.3.23 Le soupçon injuste

And his comfort with large scale architectural scenes and multi-figure work also makes him surefooted in adapting the strange dream scene in S4.11, Le Mécontent in which surrounded by a hostile crowd, the ruler prepares for his fate as his mistress hands his best friend the executioner’s blade

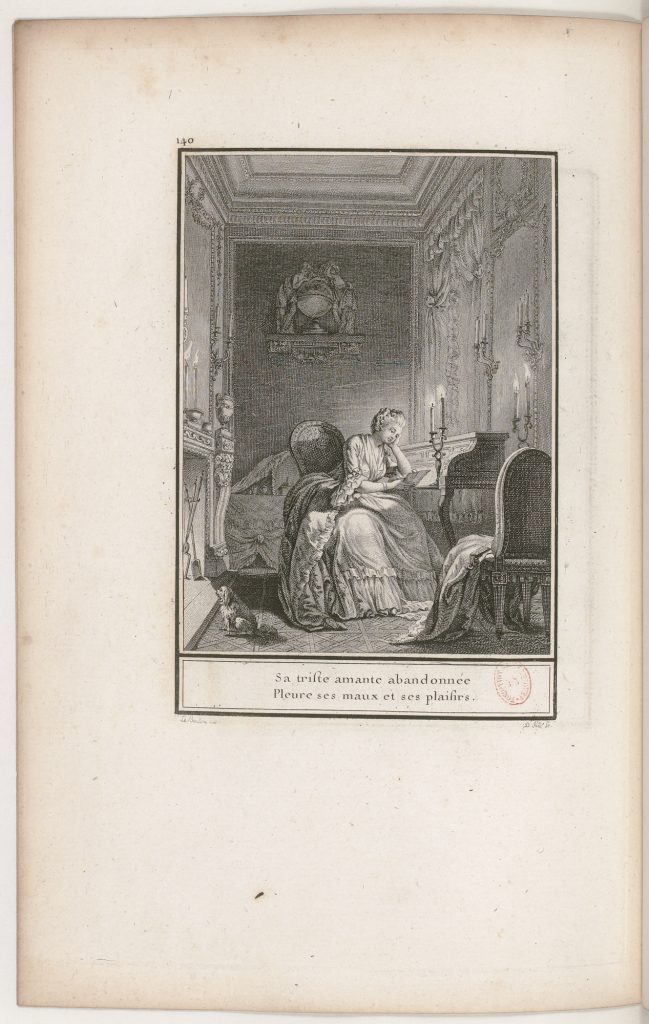

He is comfortable too rendering the subtle and elegant interior worlds of many chansons in the collection. Le Bouteux’s rather marvellous atmospheric design for 2.24, Conseils aux femmes, set the engraver a real challenge of hue and detail, but Née rose to it.

Figure 37 F-D Née after Le Bouteux, Conseils aux Femmes, Choix de Chansons, S.2.24.

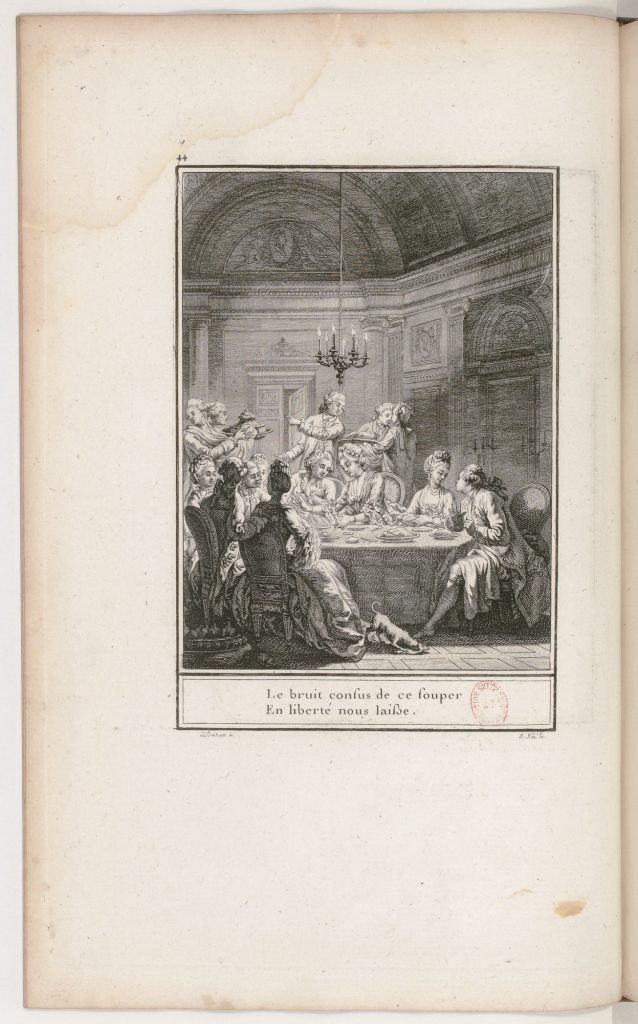

Even where Née has a huge amount of detail to fit in to a composition, such as in the crowded supper scene of Le Souper, he manages to keep the idea of both the busy and noisy supper and the intimacy of the two lovers in balance, providing a fitting visual corollary to the chanson’s music and text.

Figure 38 F-D Née after Le Bouteux, Le Souper, Choix de Chansons, S.2.08

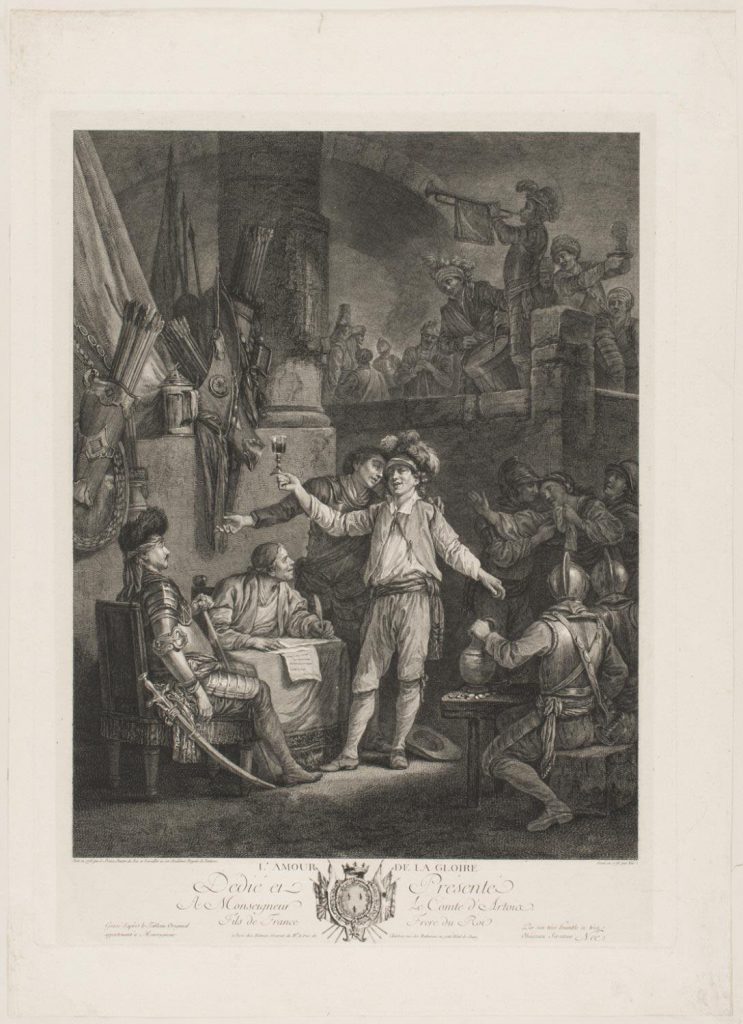

Née’s work on the Choix de Chansons not only assured him further work for La Borde on the Tableaux de la Suisse with Masquelier; he developed skills in landscape, topographical and architectural engraving and also produced reproductive engravings of some quality and originality, perhaps most notably his energetic and interpretative engraving after Jean Baptiste Le Prince’s Le Corps de Garde ou l’amour de la gloire in 1778, dedicated to the Comte d’Artois.

Figure 39: F-D Née after J-B Le Prince, L’Amour de La Gloire, etching and engraving, 1778, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

He also engraved portraits of various luminaries of the 1770s and 1780s, including (with Masquelier) publishing the intimate, ludic meeting of Jean-Benjamin de la Borde and Voltaire at Ferney in 1775, after the drawing by Vivant Denon, in the engraving Le Déjeuner de Ferney (an encounter that Nicolas Cronk has discussed on this site)

Figure 40: F-D Née and Masquelier, after D Vivant Denon, Le Déjeuner de Ferney, 1775: BNF.

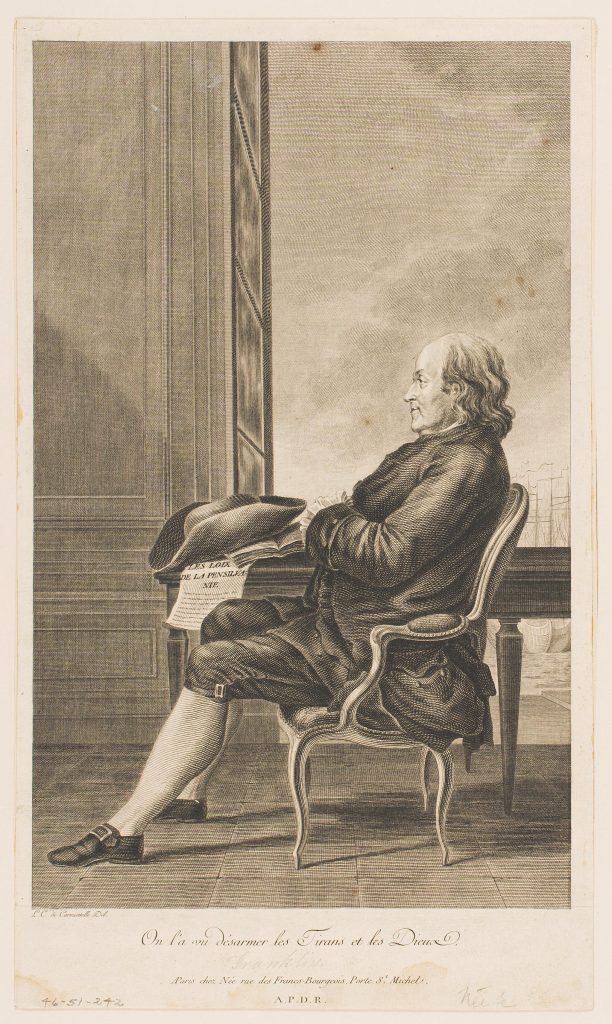

He also engraved Carmontelle’s famous profile image of Benjamin Franklin.

Figure 41: F-D Née after Louis Carrogis dit Carmontelle, Benjamin Franklin, c1781, etching and engraving, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

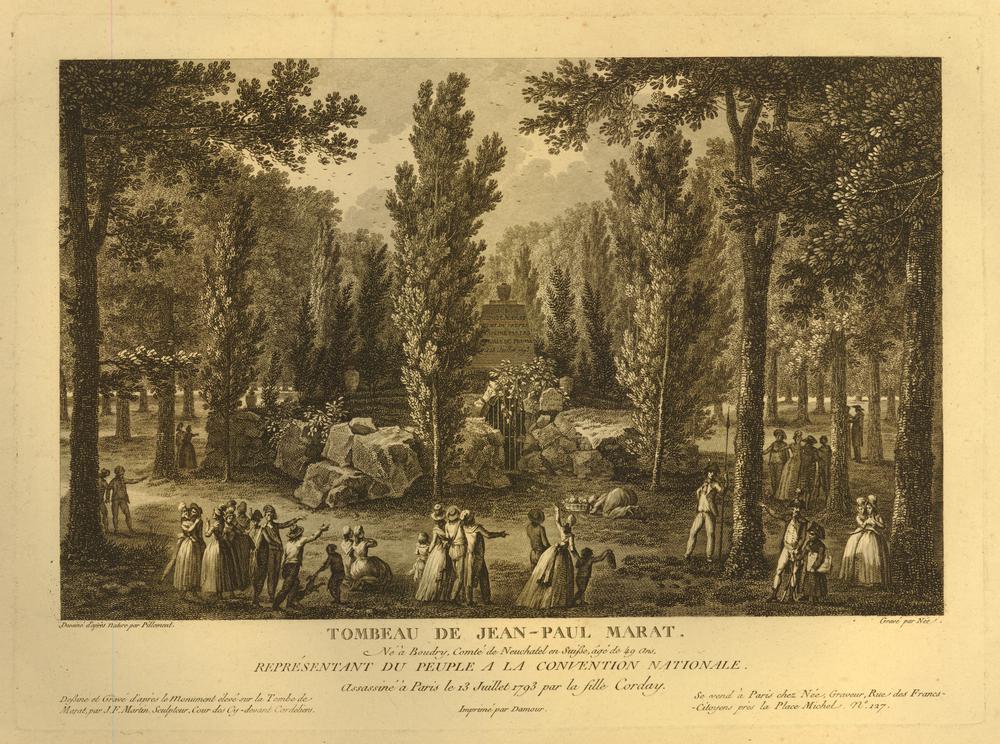

Like Masquelier, Née clearly took up new kinds of business and imagery during the Revolution, including creating engravings celebrating or commemorating Revolutionary heroes. One of the most intriguing of these was his depiction of the tomb of Marat in the garden of the Former Cordeliers convent.

Figure 42: F-D Née after Pillement, Tombeau de Jean Paul Marat, 1794, etching and engraving, London, British Museum.

Née, too, proved adapt at surviving the rapidly changing political times, (his enterprise at 127 Rue des Francs Bourgeois saint Michel (or Francs-Citoyens Saint Michel as it was renamed briefly in the Terror as the above engraving shows, or the Rue Monsieur Le Prince as it is now called) remained a place of business well into the Empire, and his work adapted to new trends and demands. In the 1790s he would become associated with many of the important voyages of exploration undertaken in the 1790s and 1800s, becoming associated especially at the end of his life as the director of the engraving for the highly ambitious Voyage pittoresque de Constantinople et des rives du Bosphore planned and organized in 1804, but which he unfortunately did not see finally published, as it emerged only after his death in 1819. [43] A letter preserved in the INHA library in Paris is a rare testament to Née’s continuing commitment to engraving at the end of his life He writes in 1815, in his eighties, deaf, but determined to further the fortunes of ..“la gravure, qui, comme vous le savés aussi, est l’art conservateur de tous les autres par son procéde Multiplicatif”. (engraving, which, as you know, is the art that preserves all the others by its reproductive techniques)

He is in this letter proud to call himself “Le Doyen de cet art [engraving] dans le genre pittoresque” and expresses his concern to ensure that French superiority in engraving is maintained. [44]

Née’s use of the term Pittoresque to describe his idiom is a reminder that “Chansons Pittoresques” was the description used by La Borde in his prospectus to lure subscribers to his innovative, ambitious and luxurious Choix de Chansons and that despite the violent and unexpectedly turbulent years that followed and the multiple changes of regime, Née retained his hunger for the ambitious, multipart, luxurious print project model that would bring particular glory to the engraver’s art.

All Downhill?

Of course, the loss of such a talented engraver as Moreau le Jeune meant that there will always be a counterfactual question for the Choix de Chansons – what would it have looked like if he alone had been responsible? Would the miraculous and deft consistency of his design and engraving style have carried through 100 engravings? There will always be those who see everything after the heights of Volume 1 as all downhill. But this essay has tried to show the many ways in which Moreau’s departure made the project expand—taking in some of the best of young talents in painting and design, highlighting the many skills of Le Bas’s other great pupils, and allowing different tones and registers in the response to the varied collection of songs. My aim has been to probe the unknown or understudied lives of those who contributed to the other 75% of the collective project of the Chansons, exploring the ways the project crowned or launched their careers. Much remains to be known, and it remains frustrating not to know anything of the fate of two of the principal designers after the 1780s. But this essay, I hope, might open the door for a more collective and generous understanding of the achievement of the project after Moreau.

Mark Ledbury, University of Sydney, 2024

I wish to thank Ana-Sofia Petrovic for her assistance in the research for this article.

[2] Choix de Chansons, Tirées Des Recueils de Chansons de M. de La Borde, Premier Valet de Chambre Ordinaire Du Roi. Dédiées à Madame La Dauphine (Paris, 1772), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k15032215.,3 : « elles ont fourni à un Artiste ingénieux divers sujets de tableaux, qu’il a destinés & gravés avec le plus grand soin ; ce Recueil aura donc le triple avantage d’amuser l’esprit, par des couplets gais & intéressants, de flatter

l’oreille par un chant facile & agréable ; enfin d’attacher les yeux par des tableaux rendus avec toute la

perfection dont M. Moreau le jeune est capable ». The Prospectus was first republished in the modern literature in the Annuaire of the Société des amis des livres, 1881, 91-105. http://archive.org/details/annuaire01livrgoog.

[3] On Moreau le Jeune, see Marie Joseph François Mahérault, L’œuvre gravé de Jean-Michel Moreau le jeune (Amsterdam: G.W. Hissink, 1979) ; Edmond de Goncourt and Jules de Goncourt, L’art Du Dix-Huitième Siècle. Gravelot. Cochin. Eisen. Moreau. Debucourt. Fragonard. Prudhon / Par Edmond et Jules de Goncourt (Paris: Quantin, 1880), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3412690x.

[4]. Ovid, Les metamorphoses d’Ovide : en Latin et en François (A Paris: Chez Pissot, quai de Conti, à la Croix-d’or, 1767-1771), See the edition at http://archive.org/details/lesmetamorphoses01ovid.

[5] Adrien Moreau, Les Moreau (Paris: G. Pierson, 1893), 59-60: http://archive.org/details/lesmoreau00more,

[6] See my discussion on this site of the Music Engravers, https://choixdechansons.cdhr.anu.edu.au/marie-charlotte-vendome-francois-moria-and-music-engraving-in-the-choix-de-chansons/

[7] The astonishing profligacy of Jean-Benjamin de La Borde is one major narrative running through the only modern biography of La Borde, Mathieu Couty, Jean-Benjamin de Laborde, ou, Le bonheur d’être fermier-général (Paris: Michel de Maule, 2001).

[8] See Mark Ledbury, « l’opéra-comique et la culture visuelle à la fin du dix-huitième siècle » in Fréderique Dassas and Barthemely Jobert, (eds.) De la rhétorique des passions à l’expression du sentiment: Actes du colloque des 14, 15 et 16 mai 2002. (Paris: Cité de la Musique, 2003)

[9] Most influentially this opinion was expressed by Henri Cohen, Guide de l’amateur de livres à gravures du XVIIIe siècle (6e édition) / Henri Cohen ; [préface par R. Portalis] (Paris: Rouquette, 1912), http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5767383t., 293-4, Entry « La Borde ».

[10] See our short biography at https://choixdechansons.cdhr.anu.edu.au/le-bouteux-joseph-barthelemy-1742-1775/ The most detailed discussion of Le Bouteux is Sophie Raux, « Joseph Barthelemy Le Bouteux: Contribution à l’étude de l’œuvre dessiné », Dessins francais aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siecles: Actes du colloque, Ecole du Louvre, 24 et 25 juin 1999, Paris, 2003, 416-30; See also exh. cat., Rouen (France). Musée des beaux arts, La Donation Suzanne et Henri Baderou au musée de Rouen : peintures et dessins de l’École française (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1980), http://archive.org/details/ladonationsuzann0000roue., 86-88. On his academician father, see also Sophie Raux-Carpentier, Pierre-Michel Le Bouteux, un académicien méconnu à Lille au XVIIIe siècle,” in Jean-Pierre Lethuillier (ed), La Peintre en Province : de la fin du moyen age au début de XXe siècle (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2002), 113-125.

[11] On this caricature see Jessica Fripp, Jessica L. Fripp, ‘Caricature, Pedagogy, and Camaraderie at the French Academy in Rome, 1770–1775’, Eighteenth-Century Studies 53, no. 1 (2019): 43–67, https://doi.org/10.1353/ecs.2019.0041., 46, 50, 59.

[12] Académie de France à Rome et al., Correspondance des directeurs de l’Académie de France à Rome, avec les surintendants des Bâtiments, 1666-[1804] (ed. Anatole de Montaiglon, (Paris Charavay frères, 1887), vol xii, 447 : « Le s’ Sénéchal, sculpteur, ayant fini sa pension, profitte de l’occasion du départ de M. de la Borde, un des premiers valet de chambre du Roy, pour s’en retourner en France ». (Natoire-Terray, letter dated 15 September 1773) The mention of « Valet de chambre du Roy” allows us to identify Jean-Benjamin.

[13] See also the proof before the “Tome II” addition in the Smithsonian American Art Museum: https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/untitled-16407

[14] Archives Nationales, Registers of Minutier Central, RE/X/14, mariage of a certain “Bathélemy Joseph Le Bouteux » to Marie Louise Basse, 9 June 1777. We also know (or think we can assume) that Le Bouteux was present at the Academy for the belated ceremony of award of his “Grand Prix” medal for his first prize of 1769 that took place on 13 April 1776, Procès-verbaux de l’Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, 1648-1793. (Paris J. Baur, 1875), 20-1 for the announcement of his winning of the prize in August 1769 and and 215-17 for the belated ceremony. Although some authorities give 1791 as a date he was alive this seems not to be backed up by any documentary evidence.

[15] Montaiglon et al, eds, Procès-verbaux de l’Académie Royale de peinture et de sculpture (1648-1793), publiés pour la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art Français d’après les registres originaux conservés à l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts : par M. Anatole de Montaiglon. (Paris: Collin, 1911-26), vol. 7: 200-1.

[16] This rare volume is bound in a ‘receuil factice’ at the Bibliotheque Nationale, see Nouveau Recueil de parures de joyailleriehttps://bibliotheque-numerique.inha.fr/viewer/49346 =

[17] Correspondance des Directeurs de l’Académie de France à Rome… (Paris: Charavay, 1887-1912), Vol 12: 93, no 5586, 20 September 1765, (Brevet)

[18] Corr. Dir, 12, 89, no 5860.

[19] Corr. Dir, 12, 246, no 6105, Natoire to Marigny, 6 August 1769: « Le sieur Saint Quentin vient de partir pour s’en retourner en France, voulant proffiter d’un bâtiment [sic for ‘bateau ?’] qui partoit pour Marseille. Cela l’a déterminé à s’en aller sans attendre le pensionnaire qui doit le remplasser ».

[20] See Corr. Dir., 12, 191, Natoire to Marigny, 23 March 1768 about the delay in Saint Quentin sending an “Académie peinte” back to Paris.

[21] Bernadette Fort, ‘Intertextuality and Iconoclasm: Diderot’s “Salon of 1775”’, Diderot Studies 30 (2007): 209–45.

[22] Denis Diderot, Salon de 1775, in Salons ed Jean Seznec, (Oxford 1967), IV, 275: « Il avait présenté à l’Académie successivement trois ou quatre tableaux d’agrément et ils avaient été tous rejettés”.

[23] J.-J. Guiffrey, ed., Livret de l’exposition Du Colisée (1776) ; Suivi de l’Analyse de l’exposition Ouverte à l’Elisée En 1797 ; et Précédé d’une Histoire Du Colisée (Paris: Bauer, 1875), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k56775431., 35-6 and 47, nos 106-117 and 210 of the catalogue.

[24] Louis Courajod, L’École Royale des Élèves Protégés: précédée d’une étude sur le caractère de l’enseignement de l’art français aux différentes époques de son histoire et suivie de documents sur l’école Royale Gratuite de dessin fondée par Bachelier (Paris: J.-B. Dumoulin, 1874), 162-3.

[25] J.-M. Schmitt, « Les artistes à la fabrique : graveurs et dessinateurs au service des établissements Haussmann du Logelbach à la fin du XVIIIe siècle », Annuaire de la Société d’histoire et d’archéologie de Colmar, 1980-1981, esp. 107-9, 122 ; claims he worked there from 1778 « aux alentours de 1785 ». https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9752014j/f134.image.r=Quentin See also

[26] Lina Beck-Bernard, Théophile-Conrad Pfeffel de Colmar: souvenirs biographiques (Lausanne: Chez Delafontaine & Rouge, 1866).

[27] Florence Fesneau, ‘L’identité Du Dormeur En Question: De l’expérience Du Sensible à La Représentation Du Cauchemar’, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 45, no. 2 (2022): 189–206, https://doi.org/10.1111/1754-0208.12793.

[28] Jean Racine, Œuvres complètes, avec des examens sur chaque pièce, précédées de sa vie et de son éloge, par Laharpe (Paris: Sautelet, 1829, vol 3, 304-7.

[29] Procès-verbaux, 9, (1780-1788), 22 (29 April, 1782) « Envoi d’une edition nouvelle de Gessner d’après M Le Barbier, peintre …etc. ». From Le Barbier’s enthusiastic dedicatory words in the first published volume in 1786, it’s clear that he wanted readers and viewers to know he was morally and emotionally in tune with Gessner’s tales.

[30] Salomon Gessner, Œuvres, Paris: l’auteur des estampes, veuve Herissant, et Barrois l’ainé [1786-1793], see Dedication. See Cohen/De Ricci, 433.

[31] Procès verbaux, 9 (1780-1788), 29, 29 July 1782.

[32] On Le Barbier’s Revolutionary career see Standen, Edith A. “Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier and Two Revolutions.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 24 (1989): 255–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/1512884. On the Declaration, see Caroline Warman, ed. “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, 1789.” In Tolerance: The Beacon of the Enlightenment, 1st ed., 3:11–13 (London: Open Book Publishers, 2016). http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt19b9jvh.6.

[33] On Le Barbier’s illustrations for this project see Kwinten Van De Walle,. “The French Translations of Thomson’s The Seasons, 1754–1818.” Translation and Literature 27, no. 2 (2018): 141–64. [154-5] https://www.jstor.org/stable/26540394.

[34] Morgan Library 2006.43:1-107; See Cara D Denison, French Drawings, 1550-1825. New York : Pierpont Morgan Library, 1984, no. 121

[35] Le Bas surprisingly lacks a modern biographer; for an account of his work, see Roger Portalis and Henri Béraldi, Les graveurs du dix-huitième siècle (Paris: D. Morgand et C. Fatout, 1880), http://archive.org/details/p2lesgraveursdud02portuoft., 564-592; Edmond de Goncourt and Jules de Goncourt, Portraits intimes du dix-huitième siècle (Paris: Bibliothéque-Charpentier, 1903), 289-314.

[36] See Pascal Torres, Les Batailles de l’empereur de Chine. La gloire de Qianlong célébrée par Louis XV, une commande royale d’estampes (Paris: Musée du Louvre/Éditions Le Passage, 2009).

[37] Jean-Benjamin de La Borde and Beat Fidel Zurlauben, Tableaux Topographiques, Pittoresques, Physiques, Historiques, Moraux, Politiques, Littéraires de La Suisse. Tome 1er : “Tableaux de La Suisse, Ou Voyage Pittoresque Fait Dans Les Treize Cantons et États Alliés Du Corps Helvétique…. (Paris : 1780), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1033019, prospectus, « Noms des Souscripteurs », n.p.

[38]. Ovid, Les metamorphoses d’Ovide : en Latin et en François (A Paris : Chez Pissot, quai de Conti, à la Croix-d’or, 1767-1771), http://archive.org/details/lesmetamorphoses03ovid.

[39] Claude-Joseph Dorat, Les Baisers, Précédés Du Mois de Mai, Poëme, 1770, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k10568480.

[40] Jean Racine, Oeuvres. Avec des commentaires par J.L. Geoffroy (Paris: Le Normant, 1808), http://archive.org/details/oeuvresraci01raci.

[41] Antoine Bret, ed, Oeuvres de Molière, Avec Des Remarques Grammaticales ; Des Avertissemens et Des Observations Sur Chaque Pièce, Par M. Bret.. (Paris: Lambert, 1773-81).

[42] Barthélemy Imbert, Le Jugement de Pâris. Poëme En IV. Chants (Amsterdam: n.p., 1772), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1095052x.

[43] For Née’s position as director of the engraving for the project, see the Prospectus, Voyage Pittoresque de Constantinople et Des Rives Du Bosphore, d’après Les Dessins de M. Melling, Dessinateur et Architecte de Hadidgé-Sultane, Soeur de l’empereur. Un Volume in-Folio, Format Atlantique. Prospectus (Paris, n.p., 1804), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k850779t.

[44] F-D Née to Charles Gilbert Terray Morel-Vindé, 22 September 1815, INHA, Autographes 035