Figure 1 J-M Moreau, Le Printems, engraving for vol.1 of the Choix de Chansons, (Library of Congress, Rosenwald collection)

“It gave to the voices of the lovers, in the pastoral of Longus, murmurs of rivulets; to their lips blushes of roses; to their kisses the chastity of angels. In their eyes are their souls reflected, filled with Heaven. They are radiant with beauty and gracefulness, and guarded by their innocence, by their ignorance, by the calm and refreshing nature that surrounds them and that their happiness enchants. It took from the Farmers General, and from the Governor of the Louvre, their fields, their forests, their vines and their prairies, and changed them into the satins, velvets, brocades, silver, and diamonds of incomparable engravings.”

This is the description of the Choix de Chansons given by Henri Pene du Bois in one of the more curious works of nineteenth-century bibliophilia, the “Four Private Libraries of New York”, of 1898.[1]

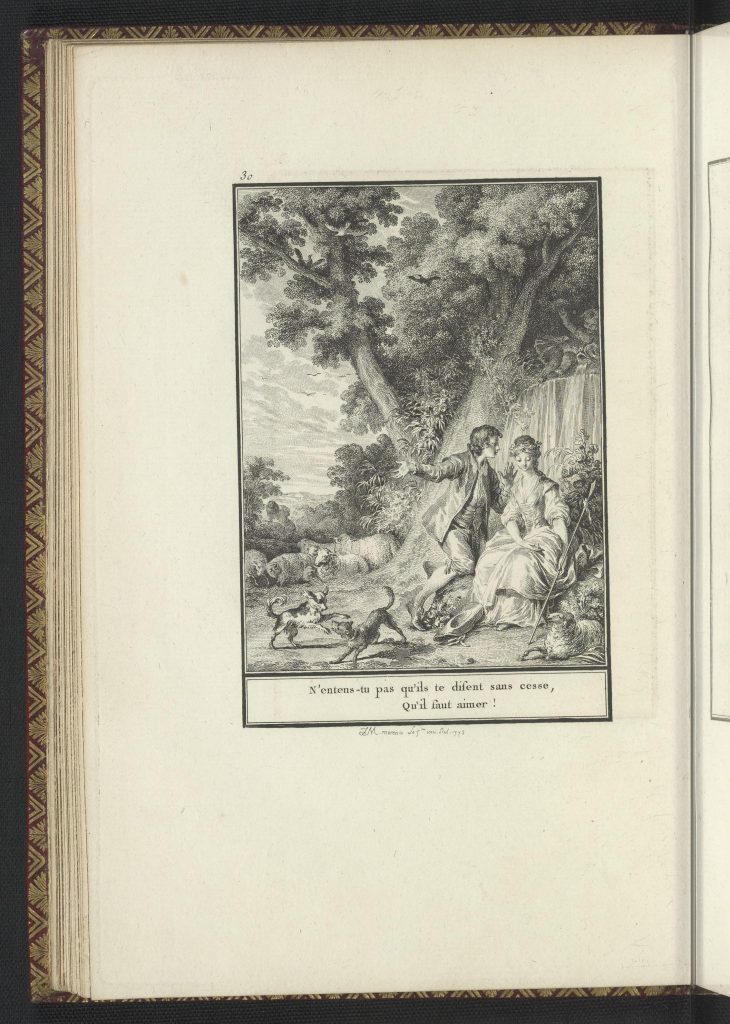

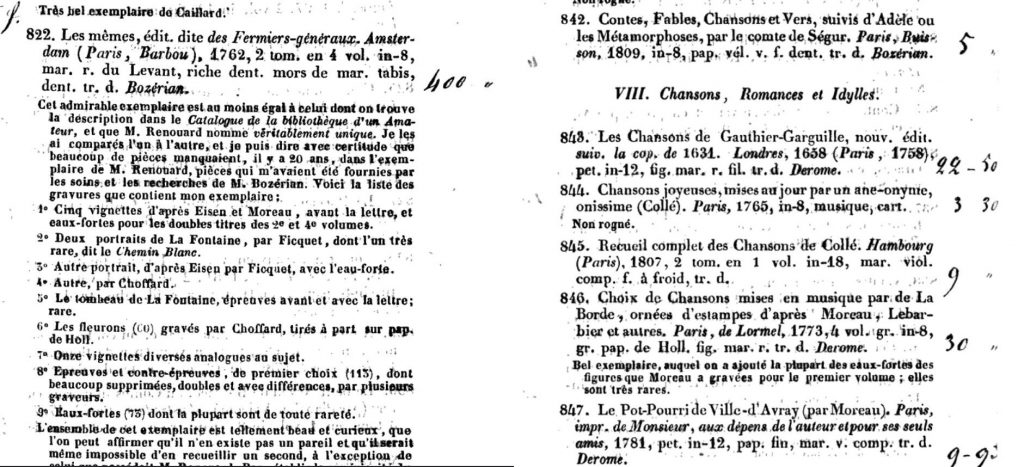

It is perhaps ironic that a project like ours, which seeks to unpack, explore and present the Choix de Chansons in new ways via digital means, has as its object of focus a work that, as a physical entity and as a luxury commodity, in its restrained large octavo physical form, became one of the most coveted and prized books in bibliophile history. Specialist historians of the book have ranked the Chansons among the “masterpieces of French book illustration”, and compared the set to the other cult work among book collectors, the 1762 Fermiers Généraux edition of La Fontaine’s Contes et Nouvelles en vers.[2]

Figure 2: Joconde, from Jean de la Fontaine, Contes et Nouvelles en Vers, ( 2 vols, Amsterdam Barbou, [Paris] 1762, Vol 1 (Paris: BNF)

Most famously, the nineteenth-century bibliophile collectors bible compiled by Henri Cohen, pronounced:

Ce livre, un des plus beaux du xviiie siècle, en est peut-être, avec les Contes de la Fontaine les plus agréable par la grâce des sujets et la variété des costumes qui y sont représentés[3]

(This book, one of the most beautiful of the eighteenth century, is perhaps, with the Contes of La Fontaine, the most pleasing by the grace of its subjects and the variety of costumes it presents)

And as recently as 1991, the catalogue entry for the Choix de Chansons in a celebration of the Rosenwald collection at the Library of Congress, James Pruett wrote

In sheer beauty of musical book production, it far outstrips practically any musical publication of the eighteenth century, in France or elsewhere… a marvel of artistic and technical quality, an achievement of the highest order within the history of French printing,… A jewel within the collection…[4]

Given its chequered publication history, its extravagance and its financial lack of success for Laborde or his collaborators, it is remarkable to chart the fall and rise of the Choix de Chansons as an object of bibliophilia, even bibliomania. This essay will chart some aspects of this journey and analyse what this might tell us about the desires, fantasies, ideas and ideologies that helped maintain the reputation of this modestly sized, but immodestly ambitious, through-engraved four volume gem whose production history was so chequered and whose very existence improbable.

A Non-Commercial Venture

As Robert Wellington has discussed in his article on the prospectus for the Choix de Chansons, Jean-Benjamin de Laborde was ambitious for the scope and quality of his songbook, which was to be both original and luxurious. Laborde chose the engraver of the moment, Jean-Michel Moreau, to create the images, and the duo of Marie-Charlotte Vendôme and François Moria to engrave music and text throughout, the whole to be printed, The various tribulations of the project, (and Laborde) during the last years of the reign of Louis XV, including the still mysterious dispute that severed Laborde’s engraving lynchpin, Moreau from the enterprise early in its life, did nothing to dampen the ambition of Laborde to ensure that his songbook would be an object of beauty, and indeed in its final form it is significantly larger an enterprise than the prospectus announced.

Laborde had, in the years before the Songbook crystalised as an idea, invested heavily in schemes that would bring ‘lustre’ and perhaps lucre, to him, his entourage and to France. It appears, though, that the Choix de Chansons, like many of Jean-Benjamin de Laborde’s other complex and costly ventures in the world of the arts and letters, did not enjoy commercial success and were, ultimately bankrolled by his family interests in the Ferme or (after 1762) his closeness to Pompadour and the King.[5] In fact, it seems to me perfectly reasonable to doubt that Laborde truly ever believed the Chansons would be lucrative, and given that he must have been aware in the early 1770s that his court favour was diminishing with the death of Madame de Pompadour and the ill-health of Louis XV, it might be argued that the subscribers were irrelevant- he came to see the Dauphine as the one true client of the songbook, and the work would be an extravagant gift to the new court that would develop around her.

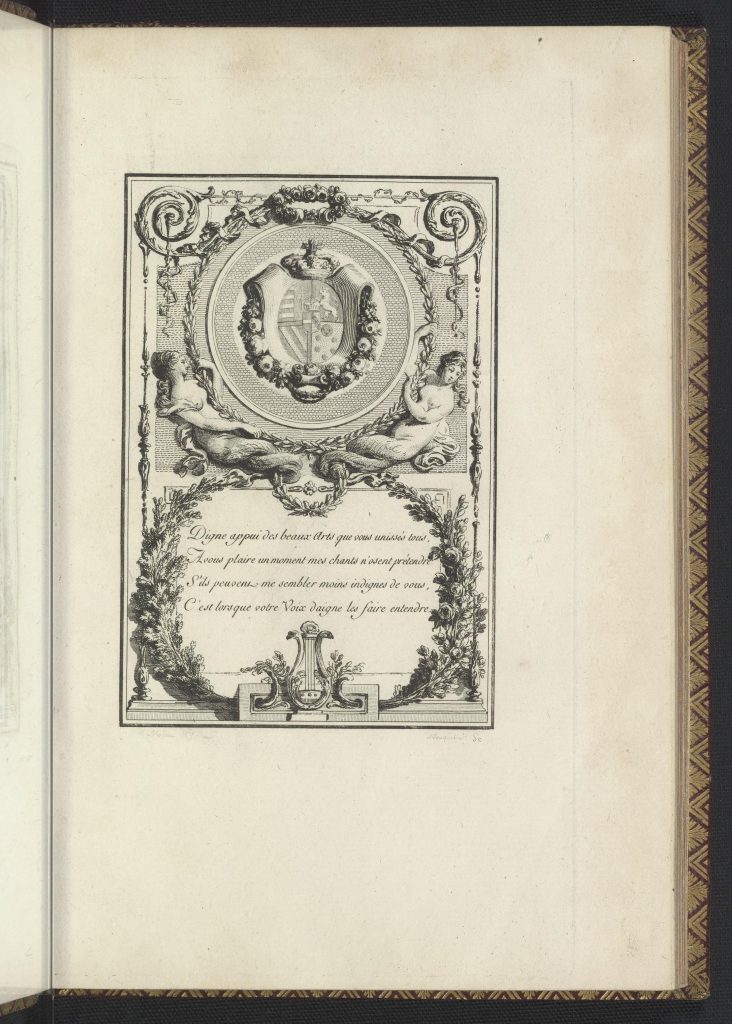

Figure 3: Dedication to the Arms of Marie-Antoinette, Choix de Chansons, vol. 1: Library of Congress, Rosenwald Collection

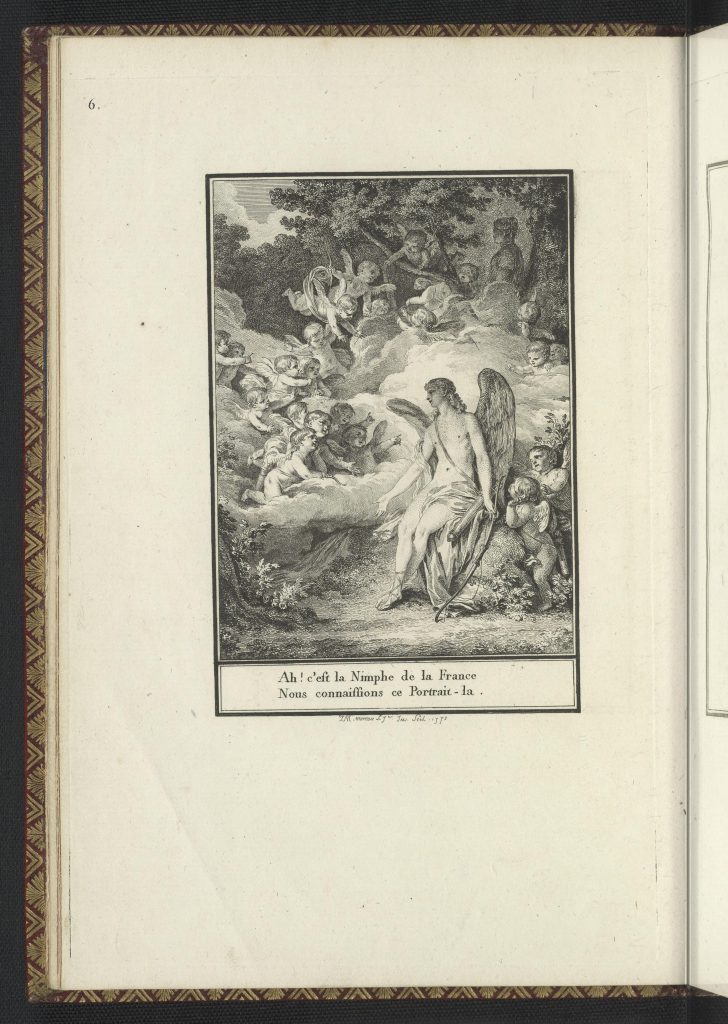

Figure 4: Le Nimphe de la France from Choix de Chansons, Vol. 1, (Library of Congress, Rosenwald collection)

In other words, the Choix de Chansons was never meant to be commercially lucrative or even break even, but instead become part of an economy of luxury and distinction.[6] It was a precious and somewhat exclusive little gem, something of a (less practical) “Birkin Bag” for the Dauphine and her entourage, exclusive, difficult to reproduce, sought after, as well as (I would contend) a nostalgic token of a passing aesthetic moment of pastoral song and gallant humour.[7]

The Choix de Chansons was indeed likely to have been part of a gift economy at court, with multiple copies circulating in Marie-Antoinette’s circle. Sarah Grant has discussed the Princesse de Lamballe’s copy of the Choix de Chansons, which may well have been a gift from the Queen or from Laborde himself; In the Rothschild library at Waddesdon is a rare small quarto printing of the Choix de Chansons which bears the inscription “Donné par Sa Majesté la Reine de France, Marie Antoinette, à Mademoiselle Charlotte de Villette, alors agée de Six ans” What a six-year old would make of some of the content of the songs is anyone’s guess, but Charlotte’s mother was the close confidante of Marie-Antoinette, Reine-Philiberte Rouph de Varicourt, marquise de Villette (1757-1822), and her uncle François had died trying to prevent the October 1789 assault on Versailles, and it seems this gift was given by the imprisoned Marie-Antoinette in 1792.[8] We know of copies that were in possession of other members of the court and a number have the arms of Marie Antoinette including the one in Rouen.[9] This kind of penetration and circulation of the Choix de Chansons in the highest echelons of the new court, was we suspect, the real aim of the volume, and of some comfort to Jean-Benjamin de Laborde as he settled into a life of post-court semi-exiled domesticity and scholarly research in the 1780s.

Revolutionary Fortune

Not unexpectedly, the fortunes of the songbook rapidly declined during the Revolutionary ruptures and the violent end of the court culture that had spawned and nourished it. We do find the work being among official Royal lottery prizes offered in 1790, indicating its continuing ‘luxury object’ status.[10] However, in the years that followed, the wholesale confiscations, and forced sales of emigrés make it difficult to track with any certainty the relative or absolute value of the Choix de Chansons as an object. However, we might see the relatively low price paid for the Choix de Chansons in the sale of Mirabeau’s collection in 1792 an indication that in the heat of the Revolutionary moment the songbook struck the wrong note.[11]

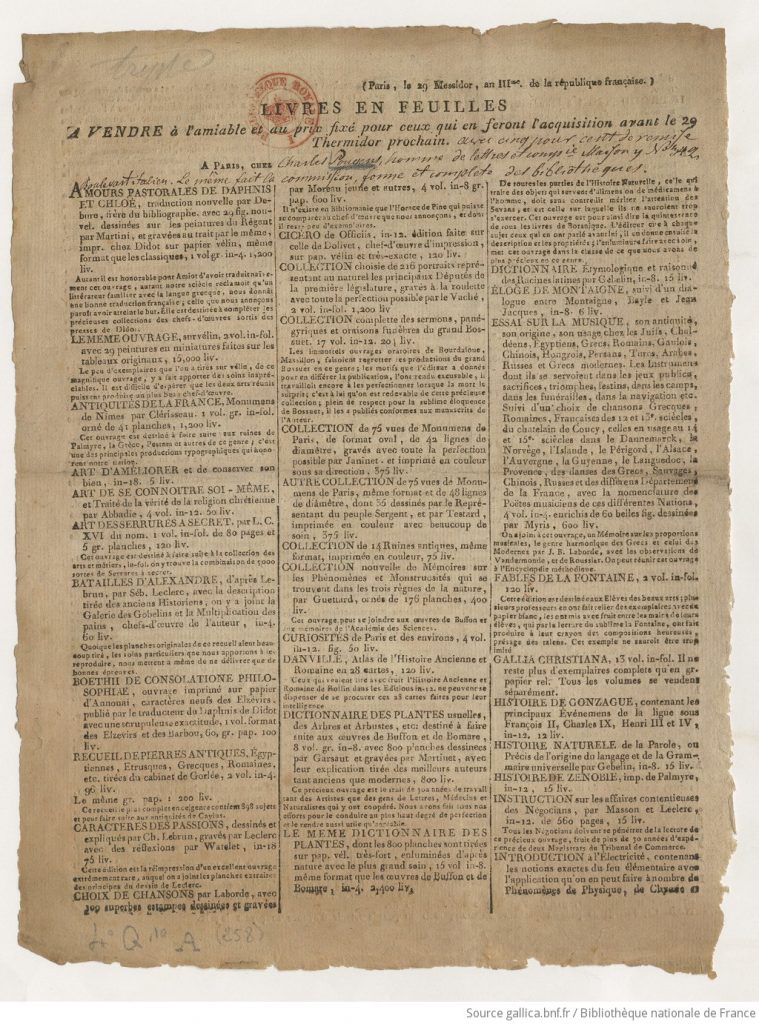

There is some evidence, however, that for the aristocratic collectors whose funds and energies survived and even benefited from the ruptures and seismic changes that affected the whole of Europe in the Revolutionary decades, the Choix de Chansons regained a place in the pantheon of bibliophile gems. A loose-leaf advertisement now in the BNF, advertises the wares of the aristocratic survivor of the Revolution turned Bookseller, Charles de Pougens, who lists for sale in 1795 among a series of desirable books, the Choix de Chansons, and proudly proclaims:

Il n’existe en Bibliomanie que l’Horace de Pine qui puisse se comparer au chef-d’œuvre que nous annonçons, et donc il reste peu d’exemplaires.[12]

[As far as bibliomania goes, only Pine’s Horace can be compared to the masterpiece we’re advertising and only a few copies of it remain]

Figure 5: Livres En Feuilles à Vendre à l’amiable et Au Prix Fixé Pour Ceux Qui En Feront l’acquisition Avant Le 29 Thermidor Prochain., 1795, Paris: BNF (Gallica).

Clearly this is a precious indication that, booksellers patter or not, the Choix de Chansons retained a place in the bibliophile imagination in the 1790s, and was beginning to be harder to find, though here the copy was for sale for a relatively modest 400 liv. (compared to, say, the Didot “Amours Pastorales de Daphnis et Chloe” which was priced at 1200 liv).

The bookseller Keck in Strasbourg had a copy of the Choix de Chansons for sale in 1797 for 168 ff, an elevated sum but not as elevated as that for, say, the grandly illustrated folio edition of Gessner’s Contes illustrated by Le Barbier among others.[13] But it is clear that as the bibliophile networks gathered again in the wake of the most intense years of the Revolution, the songbook regained some lustre with collectors. At the sale of the Montpelier scientist Jean-Jacques Brunet, in 1800, the Choix de Chansons was priced at a respectable 60 francs, but prices for the La Fontaine fermiers-généraux contes were higher.[14]

One example ended up in the library of the is the Russian Count and bibliophile, Dimitriĩ Petrovich Buturlin, (1763-1829), whose catalogue calls it a “Superb work”, and makes explicit in the introduction that the troubles of the Revolution and wars allowed precious books to find their way north.[15] An irony is that this whole library was destroyed in Napoleon’s burning of Moscow only a few years after this catalogue was compiled. Other prominent bibliophiles who ensured they had a copy of the Choix de Chansons in their collection was the diplomat and survivor Antoine-Bernard Caillard, whose extensive library was famous for its rare texts on ancient history and literature, but which also included the Choix.[16]

Changing Tastes

As luxury book production resumed after Thermidor, we can track during the Consulate and Empire the story of a developing “Didot” taste, for grander and larger scale publications of ancient texts in a neo-classical idiom, and this trend does certainly seem to have dented for a while the relative desirability of the Choix de Chansons among collectors. We also know that as far as actually being the basis of any real domestic musical activity, the Choix de Chansons’ collection of songs, already a little backward looking in 1773, had succumbed to waves of new song and new taste in the intervening years. As tastes in music and in domestic music making changed, as the fortepiano replaced the harp and harpsichord, so the musical idiom and arrangements contained in the choix de chansons must have seemed even more distant, and those men and women who had participated or felt nostalgia for the court culture that produced it were now thinner on the ground.[17] By this time then, the Choix de Chansons now only had an existence as a luxury object of a particular kind, and as such a luxury object, its stock fell during the Consulate and Empire. We can track this in the auction records and other data: At the 1812 Nardot sale, the Choix de Chansons fetched a respectable but not astonishing sum of 29.50 Francs, paling in comparison to illustrated works of the Didots published in the 1790s with a different aesthetic.[18]

The Restoration of the Bourbons in 1815 may have seen an attempt at revival of court culture, but didn’t seem to help the Choix de Chansons achieve new prominence. In the 1820 sale of Bayard de Plainville, the Choix fetched a comparatively underwhelming 10 Francs, failing to compete with some fairly modest editions of eighteenth-century authors.[19] In the same year the Choix de Chansons fared better at the Despreaux sale, sold for 25 Francs, but its price was dwarfed by that paid for the 1767 illustrated Metamorphoses.[20]

The real dip for the Chansons, though seems to begin only after the end of the Restoration. In the sale of the writer, collector and teacher Pierre de la Messagère, in 1831, for example, the Choix de Chansons was sold for a very modest sum of 12.95 l, whereas enthusiasm was much greater for more recent productions such as the collection of newly fashionable troubadour poetry edited by Reynouard, which fetched nearly five times as much.[21]

The Nadir: The Pixérécourt Sale

This dip in the fortunes of the Choix de Chansons was chronicled (in retrospect) by Henry Cohen and his successor Seymour Ricci’s bibliophile bible, the Guide de l’amateur de livres à gravures du XVIIIe Siècle, sixth edition, and the low point Cohen pointed to account of the fluctuation of fortunes in the Choix de Chansons story was the sale in 1838 of the astonishing library of one of the Revolutionary generations great writer-bibliophiles, the dramatist Rene-Guibert de Pixérécourt (1773-1844). In this annotated copy of the Pixérécourt sale, we see that indeed, as Cohen had noted, the fine copy owned by the author was sold at the most underwhelming price of just 30 Francs.

Figure 6: Pages from an annotated copy of Catalogue des livres rares et precieux et de la plus belle condition composant la bibliotheque de M.G. de Pixerecourt,.. (Paris J. Crozet, 1838) Digitized by Google and at Archive.org.

This wasn’t some generalized trough for all ancien-regime books – in the same sale, the very special “Fermiers -Généraux” edition of La Fontaine’s contes from 1762 sold for the much riper sum of 400 Francs plus premium.[22]

However, we might argue that there was something new in the bibliophile air: a new vogue for decorated and highly tooled bindings, as well as the power of new literary movements in force in 1838, – the Romantic wave that Pixérécourt had himself had a hand in creating, and which when it looked back admired most of all older literatures including that of medieval France, probably did account for some of the Songbook’s slide into disfavour. Indeed the comparison with the La Fontaine Contes at Pixérecourt’s sale is instructive here. Jean de la Fontaine, and his idioms of the fable and the tale, had managed to retain their interest for the Romantic generation, an interest galvanized by the revival of the Fairy tale and the fable, and thus La Fontaine remained a touchstone for literary creators and readers even of the new generation. On the other hand, the assorted authors and particular pastoral idiom of the Choix de Chansons might exactly have fallen into the category described by Stendhal in his polemical “Racine et Shakespeare” of 1823/5, about classicism in general:

Romanticism is the art of presenting people with literary works which, given the current state of their social customs and beliefs, are susceptible of arousing the most possible pleasure. Classicism, on the contrary, offers them that literature which gave the greatest possible pleasure to their great-grandfathers.[23]

While far from what we think of as ‘classical’, we might argue that the Choix de Chansons was born old, being already in 1773 slightly backward looking in its nostalgic repertoire of pastoral and gallant music and imagery, must have made it seem to the generation of 1830 very antiquated.

Moreover, perhaps there was a lingering after-effect in the 1830s sales, among the circles of the highly educated and often liberal-leaning bibliomanes, of the disgust with the much-hated Charles X, (1825-1830) whose ultra policies had provoked the 1830 Revolution. He was none other than the reactionary, widely despised and thoroughly implicated Comte d’Artois, Louis XVI’s brother, who had been so intimate a part of Marie-Antoinette’s theatre and music circles, and whose shadow might have been detected in the tone and make-up of the Choix de Chansons.[24] Certainly, we no longer get so many vivid and positive descriptions of the work in sales catalogues. In the Bulletin du bibliophile in 1838, edited by Charles Nodier on behalf of the bookseller Techener to highlight his stock, little fuss is made of the Choix de Chansons on sale at 65 l., which was far cheaper than, say, the complete and highly contemporary works of Schiller in 1824 edition.[25]

Whatever the reason, there is further evidence in the salerooms of the 1840s and 1850s that the Choix de Chansons fall from favour was persisting, even when much else related to the literary past was proving interesting once again. In one prominent sale, the Choix fetched only 50 ff, where other receuils of songs fetched 90, and a marked preference was shown for seventeenth century works at the sale in general.[26] Some unusual and rare variants did still appear, for example one of the small quarto printings (rather than the standard large octavo) was offered at the Crozet sale in 1841.[27] But they were never the stars of the show, and often fetched disappointing prices, as for example in the Clicquot sale in 1843, where the Choix de Chansons fetched a modest 25 ff.[28]

The ruptures and regime change of 1848-51 unsurprisingly didn’t help the fortunes of the work, from the evidence of sales like that of “M. E.B” in 1850, at which the 80ff paid for the Chansons didn’t compare favourably to, say, Ravrio’s Mes délassements, (1812) also in some ways a songbook but seemingly with greater appeal to contemporary bibliophiles, or to Lord Byron in translation.[29]

Rococo Revivals

Only in the 1860s do we begin a new chapter in the story, and it is indeed from this moment that the ascendancy of the Choix de Chansons as an object of bibliophile desire begins. One catalyst for this new phase might be found in the literary sphere rather than the auction room. The Goncourt Brothers, Edmond and Jules, began their series of archival and literary engagements with the culture of the eighteenth century with publications on the Revolution and the Directory in the 1850s, but at the end of that decade their research and writing focused more on the culture of the court before the Revolution, in a series of books emerging in succession between 1857 and 1862, books with focus on the great actress, wit and sexual adventuress, Sophie Arnould (1857); They then turned to Marie Antoinette (1858); then flowed biographies fuelled with new archives and anecdotes relating to Pompadour and Du Barry, (those only completed in the 1870s but trailed by their Maitresses de Louis XV in 1860. In the guise of new histories of the eighteenth-century, their biographies were new fountains of myth and new re-imaginings, sympathetic and engaged, of the years of court culture so explicitly captured in the Choix de Chansons. No wonder, then, that in their odd but highly influential La Femme aux dix-hutième siècle of 1862 they explicitly mention and quote Laborde’s songbook.[30]

The Goncourts, of course, were not the only artists and writers finding new interest and engagement with the ancien régime, partly in reaction to a present, the regime of Louis Napoleon, that seemed both so parodic and destructive. But they were influential, well-published and deeply connected with the curators, antiquarians, bibliophiles and collectors who were increasingly turning their faces back to pastoral, rococo aesthetics and the craft and creativity of a certain, mythic, ancien régime.[31] Everything about the Choix de Chansons, its origins, its luxury, its permissiveness, its entanglement with Marie-Antoinette, perfectly mapped onto this mythic vision of the eighteenth century. Now, to collect the Choix de Chansons was to become a connoisseur in the know.

The Radziwill Moment

Aside from this change in taste and perception, there was probably a more direct catalyst for the remarkable rise of the Choix de Chansons after 1860, that can be pinpointed to a day and an event. The most famous copy of the Choix de Chansons, the ur-copy, so to speak, and the one we’ve used as one of our bases for our entire project, with the full sets of preparatory drawings, various states and eaux-fortes, connections to Marie-Antoinette and so much more, had been in the collection Prince Michael Radziwill, Palatine of Vilna, who lived in Paris at the moment of the outbreak of Revolution and had taken advantage of distressed emigré sales to become a major acquirer of rare books and other material at (for example) the sales of Soubise, and La Vallière, where precious collections were dispersed. When the Radziwill collection itself came to be sold to help the descendants then in financial distress, an extraordinary opportunity presented itself to Bibliophiles. As the catalogue introduction made clear:

Ce qui distingue surtout cette collection de toutes celles que nous voyons passer en vente, c’est que, telle elle a été formée il y a près de quatre-vingts ans, telle, malgré ce long espace de temps, nous la voyons reparaître dans tout son éclat primitif.[32]

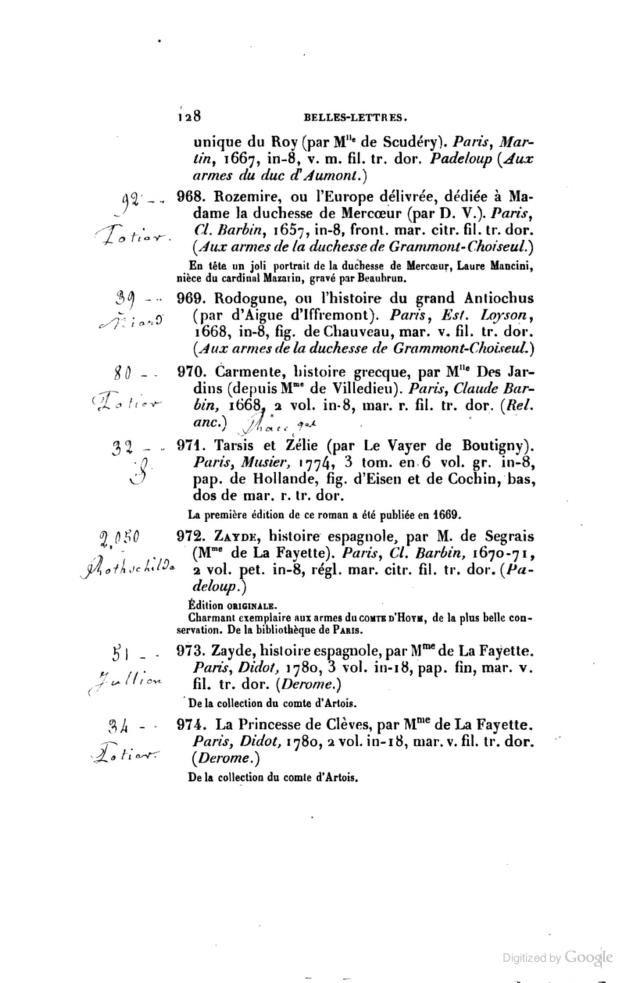

[What distinguishes this collection most from those we see coming for sale is that we are seeing it now reappearing, despite the long passage of time, just as it was when it was formed nearly eighty years ago]The collection was a precious time-capsule assembled from great and noble families, including the King’s own, and resurfacing precious and intact. The introduction, which calls attention to some of the highlights, specifically mentions the Choix de chansons among these treasures.[33] The catalogue, published in 1865, whet the appetites of bibliomanes, and when it came to the sale itself in January 1866, many major collectors were present either in person or by proxy, including famously active buyers of French rococo and ancien régime objects like the Rothschilds.

The uniquely rich copy of the Choix de Chansons, a copy rumoured to have been owned by Marie-Antoinette herself, was (I believe) the target of a bidding war in that sale, and its eventual buyer was one of the great bibliophiles of the century, and one with a particular interest in the pristinely preserved culture that the Radziwill sale presented. This was Henri Eugène Philippe Louis d’Orléans, Le Duc d’Aumale,, who, inheritor of the Condés, but exiled by Louis-Napoleon, was at the time of the sale living in London and making concerted efforts to re-assemble many of the precious collections of his royal ancestors, many of which had of course been dispersed by the Revolution. He would eventually recreate and lavishly endow the domaine de Chantilly, which he inherited from his Godfather, the last of the Condés, but at the time of the sale he could only buy through an agent (in this case Potier himself).[34]

As part of his remarkable interventions into both the art and the book markets during the sixties and seventies, the Duke purchased liberally at the Radziwill sale. But even among his other purchases, the price he paid for the remarkable, unique copy on vellum of the Choix de Chansons, with its accompanying design drawings, was extraordinary. He paid 7050 francs (which on gold comparisons, is about 70,000 euros today)

The sale contained many rare and wonderful volumes, including like first edition Montaigne, or Rabelais, or books of hours, and a magnificent example of the by then highly sought after 10 volume Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux, by Buffon et al, (which was sold for 700 ff, a tenth of the price of the Chansons.). A very fine copy of our constant ‘comparator’, the Fermiers généraux 1762 edition of La Fontaine’s contes fetched 340ff. The extreme price of the Chansons then was an absolute marker, and the result of all kinds of historical, cultural and personal desires on the part of more than one bidder -and the presence of the Rothschilds as rival bidders in the same sale might have been of significance in the final price.[35](FIGS)

Figure 7 , Catalogue des livres…de M. Le Prince de Radziwill (Paris, Potier, 1865) p.110, 824, Details of Choix de Chansons.

Figure 8: Catalogue des Livres…de M Le Prince de Radziwill, (Paris, Potier: 1865), p 128, Details of Rothschild Purchase.

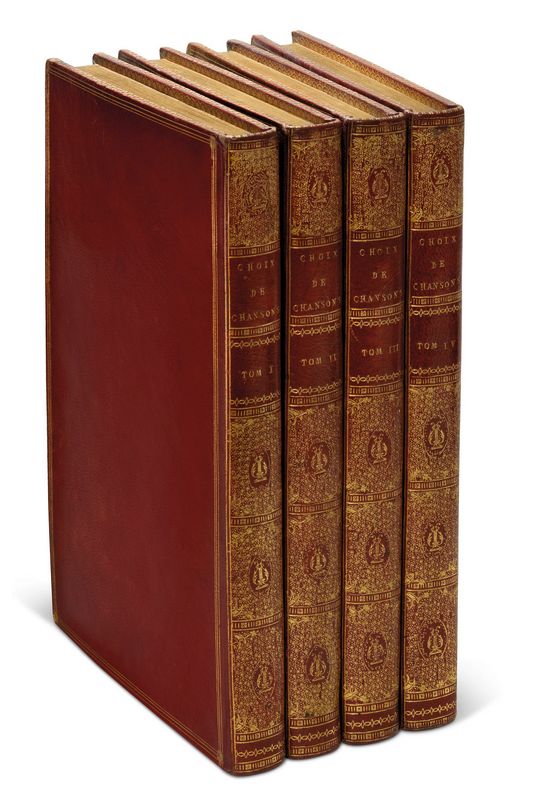

The D’Aumale Effect

This sale made the Choix de Chansons more desirable than ever, ( a second much less remarkable copy of the Choix de Chansons fetched 360ff, as the illustration shows) and its stock rose further, paradoxically, because of the violent unrest and war that marked the end of Louis Napoleon and the birth of the Third Republic. As many scholars have noted, almost as soon as peace was restored to France in the Third republic, a powerful confluence of writers, collectors and amateurs, doubled down on the revival of rococo taste, and their buying and publishing would have lasting effects on museums, collecting and taste.[36]

Under the third republic the interest in a wide range of aspects of ancien régime life, including the revived cult of Marie-Antoinette and the love of Rococo illustration, etc., continued its resurgence, as the Goncourts wrote and amplified their key studies, and collectors internationally rushed to compete for Greuze, Fragonard and others.[37] This tide of money, this wave of desire and competition for the rarest and most elegant of eighteenth-century creations, created the conditions of enthusiasm for the Choix de Chansons that would last at least until the second world war.

We can find evidence of this in the book sales records and catalogues of the 1870s and 1880s in France, Britain and the United States. The Repertoire of the Booksellers Morgand et Fatout published in Paris in 1878, (one of the first, it seems to use colour illustrations to promote its wares), featured a copy of the Choix de Chansons with an elegant binding by Lortic for 4000 fr., a very demanding price far bigger than those in the same catalogue for other sought-after works, like the 1762 Fermiers Généraux Contes et Nouvelles of La Fontaine, priced at 1, 200 fr.[38] The Chansons was in fact one of the most expensive of the items in the whole stock. Similarly, the Catalogue of the Librairie La Fontaine, in had three copies with provenances and fine bindings, all at 4000 Francs or above.[39] Such elevated prices began to create their own feedback loop of desirability, and collectors across Europe and the United States competed for this elegant and unusual time-capsule.

One sign of the new prominence of the Choix de Chansons in the culture of the Third Republic was the appearance of a very elegant and craftsmanlike facsimile, published by Lemonnyer in Rouen in 1881. Some collectors worried that the “Facsimile boom” might damage sales and reputations in the book market, as the Gentleman’s Magazine complained in 1887:

The price of books, qua books, is diminishing: Reprinting in facsimile, the multiplication of handsome editions of works once almost inaccessible, and other similar causes explain this.[40]

However, the prize value of the original seemed instead to rise. Sales in the 1880s saw the continued ascendancy of the Choix de Chansons and as far as we can tell from the data available from sales catalogues and auction prices, the Choix de Chansons remained sought-after for nearly five decades, part of the persistent demand for ancien régime culture as a marker of distinction among both British aristocratic elites and in particular the new industrial wealthy.

Gentleman’s prize

Early waves of British enthusiasm included those of the ill-fated Lord Carnarvon, bibliophile and unfortunate mosquito-bitten Eygptian adventurer, who bought a fine copy from Maggs Brothers in London, who, along with Bernard Quaritch, charged elevated prices for the Choix de Chansons in their London boutiques in the early decades of the twentieth century.[41]

Quaritch and Maggs could now rely on the ‘bible’ of the collectors, the Cohen/De Ricci Guide de l’amateur…. and its assessment of the Choix de Chansons as one of the great eighteenth century books, and this reputation was reinforced by the appearance of the songbook in exhibitions of book masterpieces, most notably the one organized by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in 1924, Choix de Chefs-d’oeuvre Du XVème Au XIXème Siècle, where it was described as one of the most famous of all eighteenth century illustrated books.[42]

Prices remained high right through the 1930s in London, in the Maggs Brothers’ catalogue in 1930, we note a fine copy of Laborde’s Choix de Chansons described now as “Moreau’s masterpiece” and “The finest of the French illustrated books of the eighteenth century”, and listed at 350 pounds, whereas the 1762 Fermiers Généraux Contes et Nouvelles of La Fontaine was priced at 110 pounds, and the magnificent Fables of La Fontaine by Oudry and others was on sale at 52 pounds 10 shillings.[43]

This early twentieth century wave provoked another, larger, transatlantic one, as newly enriched American industrialists and moguls, the Walters, the Carnegies, the Mellons and the Fricks, and others of their ilk, began to compete in a race for the exquisite, the rare and specifically, the ancien-régime in their efforts to establish themselves. We note from the account of the continuers of Henry Cohen in the Guide de l’amateur sixth edition of 1912 the westward drift of the buying trend including notable copies owned by Pierrepont Morgan, Mortimer Schiff and others.[44]

The Aesthete’s part

The endearingly strange, certainly cultish publication, Four Private Libraries of New York, with which I began, by Henri Pène du Bois, is worth returning to here to consider that perhaps the cult of the Choix de Chansons was not entirely fuelled by a conservative nostalgia for the ancien régime. Its preface was by the French bibliophile dandy, Octave Uzanne, a friend and correspondent of Pène du Bois who had become famous for his contempt for ‘investors’ in books and love of the ‘art’of the book, and collaborations with contemporary artists and printmakers like Whistler, Rops and others. Uzanne’s polemical preface sets the Francophile and craft tone. Then Pène du Bois, himself a collector and journalist, and major bibliophile, sets about a stream-of-consciousness ride through the division between real book lovers and acquirers, and also makes clear his aversion to the Didots, and the neo-classical school.[45] After this, the description of four private libraries becomes a free-form slightly dizzying trip through beautiful books and their stories and heroes, from Hugo and Baudelaire to Burty. In the third section of a decidedly non-chronological work, Pène du Bois engages poetically with eighteenth-century illustration – and his account reaches a crescendo as he frames the world of the Choix de Chansons and its companions with the description with which I began this essay. But immediately preceding this purple prose, a more ironic, even snobby tone is struck as he describes the portrait of Laborde “à la lyre” (which he himself owned as we know from his catalogue).

The portrait of Laborde ornamented with a lyre, which Masquelier engraved a

year after the work was published. All the art of the eighteenth century is represented in this gift of a lyre to Laborde, this attribution of the symbol of the divine and immortal in man, made of clay but animated with celestial fire, to an uninspired, illyrical musician ! The art of the eighteenth century gave its charm unreservedly.[46]

The admiration of Pène du Bois for the work combined a modern’s distaste for Laborde’s music (something against which our own project is pushing back) but recognized it as an ode to an enchanted, lost world and admired its craft, from which he felt modern culture could benefit. For Pène du Bois, the fantastic reconstruction of the ‘fantasy world’ of the Rococo is a necessary step for collectors, artists, aesthetes who would deploy a certain spirit, a certain freedom, and a certain aesthetic borrowed from this time to fuel the powerful fin-de siècle forms that re-deployed the skills of the craftsman and the extravagance of the luxury object., This book, with its through-engraved lighteness, its specific aesthetics might be seen to inspire the extraordinary experiments of the art nouveau boom in print, illustrated books and craft revivals. There is a through line to Arthur Rackham and the illustration boom, to the private press and bookbinding revival, to the hand-crafted, the wood-engraving revival and mezzotint revivals of the later nineteenth century.[47] Perhaps then, the very fact that this wasn’t an overwhelming elephant folio, but a craft-scale project, a domestic scale luxury, and testament to a craft combination of engraver, artist and text in a kind of harmonic gesamtkunstwerk, in which a pervasive, permissive erotic frisson was everywhere detectable, gave the Choix de Chansons a special place for the aesthetes and decadents of the yellow book generation. – we know that owners of the Choix included notable French decadents like Jean de Tinan.

Magnates and Humanists

If the aesthetes and craftsmen in Europe and in the United States at the turn of the century were responsible in part for the revival of the Choix de Chansons, Other collectors in the early decades of the twentieth century came from very different spheres, and these more collectors seem to have been responsible for the maintenance of its monetary value. One example is the prodigious book collector General Brayton Ives, decorated veteran of the US Civil War, turned industrial and financial magnate, with interests in railroads, banks and the Stock exchange. Ives collected incunabula, and rare and precious books of all kinds and at his death sale in 1914, his copy of Choix de Chansons fetched a sum of US $390 (around $16000 now).[48] Ives was no dandy, and indeed his seems a classic case of the book collection acting to create a new kind of of conoisseurial cultural capital in a whole generation of American collectors, a phenomenon best known through the enthusiastic purchase of fine and decorative arts that has recently been the subject of a major exhibition and publication by Yuriko Jackall and her team.[49]

I think we might nuance this familiar story a little, though, especially should we be tempted to see it only as the guilt-washing of old industrial and banking monopolies by cultural acquisition. I would point to the continuing enthusiasm for rare books and the continued and scholarly interest in the tradition of illustrated books that drove the next ( post-Great Depression ) generation of collectors, among whom one of the most assiduous and brilliant was Lessing Rosenwald, (of the Sears Roebuck company) who collected with great vigour in the 1930s and then made one of the most important of all book donations in the world—the gift of his collection to the Library of Congress, one of America’s great public institutions. Rosenwald’s philanthropic urge and unashamed humanism was an early example of an impulse contrary to the snobbery and studied intellectual elitism of Pène du Bois or the hoarding of some of his contemporaries. Rosenwald sought out a special, beautifully preserved, bound and tooled copy of the Choix de Chansons which, thanks to his gift, is now in the Library of Congress.[50] Whether we can truly say this is already an impulse to democratize the access to the kinds of taste and beauty that were previously only available to the rich is perhaps debateable, but Rosenwald’s gift was part of a pattern by which great private collections found themselves transferred to, or transformed into, public museums and libraries.

Other progressive humanist collectors of Laborde’s songbook included Dannie Heinemann, whose 2 copies of the Choix de Chansons are among 4 copies currently in the Morgan Library in New York– one of which is indeed the copy that belonged to the decadent, revivalist siren of the Belle Epoque, Jean de Tinan. Heinemann, a scientist and engineer who had helped Jewish families escape through Luxembourg during world war 2, was a passionate collector of music history, and his interest in Laborde’s songbook was driven at least as much by his interest in the musical idiom as by its luxury.[51] Another copy in the Morgan had belonged to the great Salonnière and Music connoisseur, Madame Talien, Princesse de Chimay.[52] In a way the great collectors of the mid twentieth century were buying something that even Laborde couldn’t have foreseen – the successive histories of books that had passed through noble, artistic, notorious and culturally significant French hands down generations. The association now wasn’t just with the nostalgia for a former and grand collection and time, as it had been for the Duc D’Aumale, but a culture seen to be experimental, essential, exquisite and important to an understanding of post war humanism, as part of a wider history of how books and arts made us all, a story that also propelled the humanities boom through colleges and campuses in the post WW2 world.[53]

Another of the copies in the Morgan Library tells a similar story, it comes from the book collector, professor of English and Thackaray scholar Gordon Norton Ray, whose copy was exhibited and described by the owner himself in his The Art of the French Illustrated Book, 1700 to 1914 (exhibited in 1982) at the Morgan.[54] Ray was a WW2 veteran, professor of English at Illinois and New York Universities, and President of the Guggenheim Foundation. His interest in the Choix de Chansons exemplifies what I’d see as a brand of humanist connoisseurship that was deeply historically informed but was not particularly dewy eyed about the ancien-regime, instead was already concerned about the loss of the kind of physical, aesthetic, craft and artistic merits bound up in the extraordinary octavo of the Choix de Chansons. His concern was for the complexity and beauty, and the historical and human effort, of designers, engravers, printers, binders as well as authors, that made such endeavours possible, despite his skepticism about Laborde’s own talents.[55]

Fin de Partie? The Choix de Chansons today

As the humanities consensus erodes, and the ancien régime’s disparities of wealth and opportunity are surprisingly recreated in the wealth transfers of the 21st, it is difficult to chart where the Choix de Chansons stands now. The luxury boom of the past thirty years, that has seen the creation of new empires and brands, might have been an incentive for a new spike in the prices of such ‘gems’ as the Choix de Chansons. But against that, the funds of the super-rich now have many other distractions and targets, and bibliophilia does not have the same place in elite spending and collecting habits as it did a century ago. Even amongst bibliomanes, the modern first and the rare or anomalous volume holds more attention. Even amongst its ancien regime peers, though, it seems though, that the songbook may have dropped down a tier in desirability, especially if we maintain its comparison with the 1762 Fermiers Généraux edition of La Fontaine’s Contes et Nouvelles en vers.

As a sample, let us explore the records of sales of the Choix de Chansons at one international auction house, Christies, over the past twenty years and compare them with those of the La Fontaine Contes et Nouvelles at the same auction house. Of course, this kind of comparison is subject to many a caveat—the condition, provenance and other factors make each sale different, and of course, now many of the more spectacular, or notably-provenanced copies and those with accompanying proofs, etc, are in public collections, so others circulating may not be of equal quality, or be restored, and thus the chances that they ever achieve the dizzy heights of a century ago are diminished. With all that said, however, we note in Christies sales database that the Choix de Chansons has had a chequered and inglorious history in the thirty years between 1990 and 2020 – during which time the highest price recorded for a full and complete copy (without premium) was the 4,600 ukp paid at a sale in May 1995, a sum at the low end of estimates.[56] A copy with major restorations sold for only ukp 863 in 1998, again at the bottom of estimates.[57] The only notably high price in the years before 2020 was in fact for a copy only of the first (Moreau) volume, bought in Paris in 2003 for 5,288 euros, a sign that the engravings, and the name Moreau, was more of a magnet than the entirety of the work.[58] Overall, the Songbook found little love among the auction-going elites in those thirty years.

By comparison, the Contes et Nouvelles en Vers from 1762, held up well, with many of the copies, even those in less than perfect condition, selling for above estimates, and two copies in particular reaching stellar prices. These were beautiful copies: one, in May 2007, had the illustrious provenance of the Marquis de Marigny and sold for 24000 euros against an estimate of 6-9000 euros.[59] Two years later, another copy, with all the right naughty plates ‘uncovered’ sold for the even greater sum of 27400 euros.[60] In general then, even from this admittedly small sample, we can see that the Contesmarket value in this period was well and truly now ahead of the Chansons.

We might speculate that in the later twentieth century the end of the road was reached for the particular and intense interest in the Choix de Chansons as luxury object for several reasons. Laborde’s name is nowhere in the canon, and he can’t compete with the enduring popularity of La Fontaine. Further, the decline of a certain kind of Franco-American humanism’s sway over our sense of what’s special and refined has also contributed. But perhaps, too, because it is now so difficult to actually peruse any copy of the Chansons to get a sense of its physical or material reality, its adventurous abandonment of letter press in favour of an all-engraved aesthetic, a celebration of the Burin as multimedia tool and of the constrained, connected, improvised visual, verbal and musical rhyming across the pages. We seem to have moved too far from the kinds of connoisseurship needed to understand why this book was special, as well as distanced ourselves from the prizing of exquisite, (and elitist) materiality.

Revival?

This demise, though, might have an optimistic footnote. In the last couple of years, the years of course, in which our own project has begun to draw attention to the work again, there is some (again, scanty) evidence in the same databases of a beginning of revived enthusiasm. At Christies, since 2020, two copies of the Choix de Chansons have beaten estimates comfortably. One, not in very good condition, but with a provenance from Victorien Sardou’s library, sold well above its estimate for 5,625 Euros in 2021.[61] But most spectacularly, the copy in beautiful condition, with spectacular bindings by Bradel, from the library of Prince C. Sczaniecki, sold in 2020 for an eyebrow-raising 18,750 ukp in London.[62]

Figure 9: LA BORDE, Jean Benjamin de (1734-1794). Choix de Chansons mises en musique. Paris: de Lormel, 1773, Lot 167 from Valuable Books and Manuscripts, Christies, London, 09 December 2020: Photo from Christies Website.

And away from Christies, well-provenanced copies do occasionally break out. An example is the copy sold in 2011 by Gros et Delettrez, for 18000 euros (without premium). [63] This copy, with spectacular bindings, had the ex-libris of the the Chevalier de Fleurieu, a military man, naval expert and governor, who remained close to the Royal Family and miraculously escaped execution in the terror (though suffered imprisonment and loss of all his property) then regained status to serve the directory and consulate and empire, and was given a state funeral by Napoleon. The lot description stressed its continuing specialness for collectors: « Cet ouvrage, dans cet état exceptionnel, peut être considéré à juste titre comme le «merle blanc» par les collectionneurs de livres à figures du XVIIIe siècle. ».[64]

[This work, in this exceptional condition, might be considered the one-in-a million by collectors of illustrated editions of the eighteenth century]Conclusion

Perhaps this nomenclature, merle blanc, (literally, the “White Blackbird”) is an unexpectedly apt description for this odd, rare, one-of-a-kind, experimental, and indeed genetically unsuccessful work.[65] In tracing the fluctuations of the Choix de Chansons, its moments of glory and its rockier times, I hope to have suggested the ways in which this unusual, dense and moving object has made a surprising impact, one that was surely never foreseen by its creators, on collectors, creators, writers and artists, over the 250 years of its existence. Our project aims to unpack, explain and analyze the Choix de Chansons, in music, text and image, but I hope to have shown that its ‘object biography’ continues and develops as it finds passionate owners and new homes. With the rises and falls of this time-traveling luxury tardis, we can chart the complex history of bibliophilia, luxury and even of cultural capital, from Marie-Antoinette to our own day.

Mark Ledbury, University of Sydney, 2024

[1] Henri Pène du Bois, Four Private Libraries of New York; a Contribution to the History of Bibliophilism in America. First Series (New York: Duprat, 1892), 90-1.

[2] See for example Owen E. Holloway, French Rococo Book Illustration (New York: Transatlantic Arts, 1969), 1; Archibald Younger, French Engravers of the Eighteenth Century (London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton Kent, 1913); Henri Pène du Bois, Four Private Libraries of New York; a Contribution to the History of Bibliophilism in America. First Series (New York: Duprat, 1892), 90, where Choix de Chansons is described as the “Mate of the “Contes” of the Fermiers-Généraux” (90).

[3]Henry Cohen, Guide de l’amateur de Livres à Vignettes Du XVIIIe Siècle (Paris: Rouquette, 1870), 65 https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k54894663. This work, in its revised and continued forms, would be the key work for bibliophiles with an interest in the eighteenth century and retains its usefulness to the present day. For the expanded entry on the Choix de Chansons with de Ricci’s additions see also Henry Cohen, Guide de l’amateur de Livres à Gravures Du XVIIIe Siècle (6e Édition); [Corr., ed., Seymour de Ricci,], (Paris: Rouquette, 1912), 533-538

[4] Vision of a Collector: The Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection in the Library of Congress (Washington: Library of Congress, 1991), cat. 60. 280-1.

[5] See Mathieu Couty, Jean-Benjamin de Laborde, ou, Le bonheur d’être fermier-général (Paris: Michel de Maule, 2001), and see also the review of this book by Reynald Abad, ‘Mathieu Couty, Jean-Benjamin de La- borde ou le bonheur d’être fermier- général’, Histoire, économie & société 23, no. 1 (2004): 146–47. Abad gives the best pithy description of Laborde’s financial dealings: «courtisan dépensier, joueur invétéré, investisseur mal avisé, il vit constamment à crédit, son expérience de manieur d’argent ne lui servant qu’à pratiquer la cavalerie la plus effrénée.»

[6] On luxury and court culture, see Charissa Bremer-David and J. Paul Getty Museum, Paris: Life & Luxury in the Eighteenth Century (Getty Publications, 2011); on the influence of court culture on consumption see William H. Sewell, ‘The Empire of Fashion and the Rise of Capitalism in Eighteenth-Century France’, Past & Present, no. 206 (2010): 81–120.

[7] https://www.harpersbazaar.com/uk/fashion/a43020862/hermes-birkin-bag/

[8] See Catalogue des livres français du Baron F. de Rothschild (London: Dryden Press, 1897), 40. An identical inscription exists on a copy of the Oudry Fables of La Fontaine sold in the 1880s. see Wilkinson and Hodge Sotheby, La Bibliothèque de Mello. Catalogue of an Important Portion of the Very Choice Library of the Late Baron Seillière (Sotheby: Wilkinson and Hodge, 1887). Charlotte de Villette was the daughter of the notorious Marquis de Villette, born in 1786, this indicates the gift was made in 1792, with the Royal Family effectively prisoners. Charlotte (full name Amable-Prosper-Charlotte-Philiberte-Marie de Villette) died in 1802, and Chateaubriand records the sadness of her loss in his mémoires. See François-René de ChateaubriandMémoires d’outre Tombe: V,” accessed September 12, 2024, https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Chateaubriand/ChateaubriandMemoirsBookV.php#BkVCh15Sec1.

[9] Rouen, Bibliothèque Municipale, mm608.

[10] See Affiches, annonces et avis divers, ou Journal général de France, I July 1790, 2338

[11] Catalogue Des Livres de La Bibliothèque de Feu M. Mirabeau l’aîné,… Dont La Vente Se Fera… Le Lundi 9 Janvier 1792… (Paris: Rozet, 1791), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k15130381, 71, no 470: sold for 52 liv. 1 sol., the Choix did not command even the same sum as more orthodox chanson collections, and did not match in any way prices paid for less aesthetically eminent editions of literature and drama.

[12] Livres En Feuilles à Vendre à l’amiable et Au Prix Fixé Pour Ceux Qui En Feront l’acquisition Avant Le 29 Thermidor Prochain., (Paris, 1795), n.p.: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9800076w. Manuscript markings make clear these works are for sale by Pougens.

[13] Catalogue Des Livres Qui Se Trouvent Chez J. J. Keck, Libraire à Strasbourg., (Strasbourg: Sociète des deux ponts, An II [1797]), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9819291b., 76 for the Choix de Chansons

[14] Catalogue des livres de la bibliothèque de feu le citoyen J.J. Brunet. (Montpellier: Chez Renaud…, 1800), http://archive.org/details/cataloguedeslivr00brun_0., 161 no 1278.

[15] Charles (Pougens and Antoine-Alexandre Barbier, Catalogue Des Livres de La Bibliothèque de S. E. M. Le Cte de Boutourlin, Revu Par MM. Ant.-Alex. Barbier,… et Charles Pougens,…, (Paris: Pougens, 1805), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1513114z., no 1756, 269-70, « Superbe Ouvrage » ; see also intro, VI, for remarks on the transfer of work from France to Russia.

[16] Aubin-Louis Millin, Catalogue Des Livres, Rares et Précieux de La Bibliothèque de Feu M. Ant. Bern. Caillard,…, (Paris: De Bure, 1808), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bd6t5396973r.

[17] On changes in music and music-making in the Revolution and Romantic eras, see Malcolm Boyd, (ed.), Music and the French Revolution (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008); James H. Johnson, Listening in Paris – A Cultural History: (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995); Benedict Taylor, The Cambridge Companion to Music and Romanticism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

[18] Catalogue Des Livres de La Bibliothèque de Feu M. Nardot,… Dont La Vente Se Fera Le Mercredi 16 Décembre 1812… (Paris: De Bure, 1812), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k55097116., 21, no 258.

[19] Notice Des Principaux Articles de La Bibliothèque de Feu M. Bayard de Plainville,… Dont La Vente Se Fera Le Lundi 17 Avril 1820… (Paris: De Bure, 1820), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5523461r., p.6 annotations show the prices and the Choix de Chansons seems to have failed to attract an initial bid and sold for the lower price of 10 francs.

[20] Notice des livres de la bibliothèque de feu M. J-E Despréaux (Paris: Olivier, Royer, and Brunet, 1820): Choix de Chansons is no. 73, (p.7), sold for 25 francs; the 1767 bilingual Ovid is no 42, p.5, sold for 69 Francs 25.

[21] Catalogue Des Livres de La Bibliothèque de Feu M. de La Mésangère,… Dont La Vente Se Fera Le… 14 Novembre 1831… (Paris: De Bure,1831) ,https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5506421m. Laborde is 69. No 743; the Reynouard Troubadours is 59, no 627. (Sold for 61 Francs).

[22] Catalogue des livres rares et precieux et de la plus belle condition composant la bibliotheque de M.G. de Pixerecourt,.. (Paris: J. Crozet, 1838), http://archive.org/details/bub_gb_CV3molNjhvUC., 107, 110.

[23] Stendhal, Stendhal Racine And Shakespeare, trans Guy Daniels (New York: Crowell-Crollier Press, 1962), 38 http://archive.org/details/stendhal-racine-and-shakespeare.

[24] On the politics and culture of the period, see Philip Mansel, Paris Between Empires 1814-1852: Monarchy and Revolution, 1st edition (London: Phoenix Press, 2003).

[25] Bulletin du bibliophile, publiée par Techener avec notes… et notices bibliographiques, philologiques et littéraires par Ch. Nodier (Paris: Techener, 1838), 472, no 1200 (Laborde) and 479, no 1246 for Schiller.

[26] Bibliothèque de M. E. B… : Maison Silvestre, 28 Rue Des Bons-Enfants, 10 Avril 1850, Me Boulouze, 1850, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bd6t5404338w, 50, n 746. Annotated with price, 50ff.

[27] Catalogue Des Livres Composant Le Fonds de Librairie de Feu M. Crozet,… Seconde Partie Contenant Les Raretés Bibliographiques et Les Belles Reliures (Paris: Colomb, 1841), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5838915s, 90, no 744.

[28] Bibliothèque de F. Clicquot Autogr., Mss à Peintures, Livres Précieux : Paris, Salle Silvestre, Rue Des Bons-Enfants, 22 Avril 1843 / Com. Pris. : Lenormand de Villeneuve (Paris: Techener, 1843), 47, no 277, annotation on BNF copy.

[29] Bibliothèque de M. E. B… : Maison Silvestre, 28 Rue Des Bons-Enfants, 10 Avril 1850, Me Boulouze (Paris: Potier, 1850), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bd6t5404338w, Choix de Chansons is 746, sold for 50ff, whereas Byron’s works (no 778) went for 62ff, and Ravrio’s délassemens fetched 94ff (no 759 bis).

[30] Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, La Femme Au XVIIIe Siècle, (Paris: Didot, 1862), 133. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bd6t5372197w.

[31] On the Goncourt’s influence over taste, and their shaping of a new eighteenth-century, see Jennifer Forrest, “Nineteenth-Century Nostalgia for Eighteenth-Century Wit, Style, and Aesthetic Disengagement: The Goncourt Brothers Histories of Eighteenth-Century Art and Women,” Nineteenth-Century French Studies 34 (September 1, 2005): 44–62, https://doi.org/10.1353/ncf.2005.0054 and this talk by Yuriko Jackall. https://www.frick.org/interact/goncourt_brothers_taste_for_eighteenth_century.

[32] Sigismond prince Radziwill, Catalogue des livres rares et précieux composant la bibliothèque de M. le prince Sigismond Radziwill (Paris: L. Potier, 1865), v.

[33] Ibid, xi.

[34] For a recent discussion of the Duke’s collecting, see Tom Stammers, “Materializing France in Exile: Henri, Duc d’Aumale, the Orléans Family and the Transnational Politics of Collecting c. 1848–80,” French History 37, no. 4 (December 1, 2023): 442–67, https://doi.org/10.1093/fh/crad048.

[35] All the price information from this sale, plus the fact that Potier, the bookseller and auction organizer, was the agent for the Duke in the sale, is revealed in the marked up copy of the catalogue in the Biblioteca in Florence, digitized by Google. https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/Catalogue_des_livres_rares_et_pr%C3%A9cieux/Yj7ys3r4oeoC?hl=en

[36] See Debora L. Silverman, ‘Rococo Revival and Craft Modernism: Third Republic Art Nouveau’, in Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siecle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style (University of California Press, 2023), 107–314, https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520913288-006. See also the essays in Yuriko Jackall, Philippe Bordes et al., (Eds.) America Collects Eighteenth-Century French Painting (Washington : London: Lund Humphries, 2017).

[37] See Suzanne Higgott, Sir Richard Wallace: Connoisseur, Collector & Philanthropist: “The Most Fortunate Man of His Day”: (Pallas Athene, 2023); see also Yuriko Jackall et al., America Collects Eighteenth-Century French Painting (Washington : London: Lund Humphries, 2017).

[38] Librairie Morgand et Fatout, Répertoire de la librairie Morgand et Fatout (Paris : D. Morgand et Ch. Fatout, 1878), http://archive.org/details/rpertoiredelal00libr., 161, no 1338. “Très-bel exemplaire de ce superbe livre” for the La Fontaine Contes, 141, no 1171.

[39] Librairie Auguste Fontaine, Catalogue de livres anciens et modernes, rares et curieux de la Librairie Auguste Fontaine 1878/79 (Paris: Fontaine, 1879), 187-8, nos 731-2. https://api.digitale-sammlungen.de/iiif/presentation/v2/bsb10536892/manifest Here, too an excellent copy of the 1762 Fermiers-Généraux La Fontaine was priced at 1500fr, 179, no 697.

[40] David Henry John Nichols, The Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol 1 (1887), 416 http://archive.org/details/gentlemansmagaz178unkngoog. Copies of this facsimile have been accessioned into museums and libraries and are themselves fairly rare: see https://collections.mfa.org/objects/250781.

[41] I am very grateful to Ana-Sofia Petrovic for her research and compilation of book sales data from Auctions and Book dealers’ files, which charts the steady rise in prices through the 1890s and into the 1900s in the English speaking world. The figures that follow in these and other notes are the result of her excellent research assistance.

[42] Philippe Pétain and Théodore Mortreuil, Choix de Chefs-d’oeuvre Du XVème Au XIXème Siècle : Exposition, [Paris], Bibliothèque Nationale, 19 Mai-1er Août 1924 / [Présentation Théodore Mortreuil] (Paris: Albert Morance, 1924), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k64568539, Cat.85, «l’un des plus célèbres parmi les livres illustrés du XVIIIe siècle.»

[43] Sales Catalogue 535: Maggs Bros (London, Maggs, 1930), http://archive.org/details/b31811590, 29, no 127 for Laborde; 30-31, nos 132 and 133 for the La Fontaine.

[44] See Henry Cohen, Guide de l’amateur de Livres à Gravures Du XVIIIe Siècle (6e Édition) / Henri Cohen ; [Préface Par R. Portalis], 1912, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5767383t., esp. 536-8, mentioning copies held by Pierrepont Morgan, Mortimer Schiff and others.

[45] See Pène du Bois, Four Private Libraries (as in n.1), Préface, 5-8, and “The art of the decade”, 15-19. For Henri Pène du Bois’ own library, see Henri Pène du Bois, The Library & Art Collection of Henry de Pene Du Bois, of New York. (New York: Leavitt, 1887).

[46] Pène du Bois, Four Private Libraries, 90-91.

[47] Britany Salsbury, “The Etching Revival in Nineteenth-Century France | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History,” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, accessed September 14, 2024, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/etre/hd_etre.htm.; David Alexander, “14 Raeburn and the Revival of Mezzotint Portraiture, 1890–1930,” in Henry Raeburn: Context, Reception and Reputation (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022), 351–66, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474465847-018; on Arthur Rackham, see the classic account by Derek Hudson, Arthur Rackham: His Life and Work (London: Heinemann, 1960).

[48] American Art Association, The Literary Treasures Forming the Library of… Gen. B. Ives (New York: American Art Association, 1915), http://archive.org/details/literarytreasure00amer., no 555, sold for $390.

[49] Exh. Cat., America Collects Eighteenth-Century French Painting ( ed. Yuriko Jackall et. Al, Washington : London: Lund Humphries, 2017).

[50] See Library of Congress, The Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection: A Catalog of the Gifts of Lessing J. Rosenwald to the Library of Congress, 1943 to 1975; Vision of a Collector: The Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection in the Library of Congress (Washington: Library of Congress, 1991), especially cat.60, 280-1.

[51] Morgan Library, Heineman 275 and 276

[52] Morgan Library, PML 2376-79.

[53] Some reflections on this Humanities boom in American Universities are in David A. Hollinger, (ed.) The Humanities and the Dynamics of Inclusion since World War II (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), https://doi.org/10.1353/book.3273.

[54] Gordon N. Ray, Art of the French Illustrated Book, 1700-1914 (New York, N.Y.: Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1982). For the Ray copy, see Morgan, PML 140136.

[55] On Gordon Norton Ray’s life see the obituary in the NY Times, Wolfgang Saxon, “DR. GORDON NORTON RAY, SCHOLAR AND AUTHOR,” The New York Times, December 16, 1986, sec. Obituaries, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/12/16/obituaries/dr-gordon-norton-ray-scholar-and-author.html.

[56] https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-253234

[57] https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-1374485

[58] https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4203943

[59] https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4907624

[60] https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5220908

[61] https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6345409

[62] https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6296987

[63] Gros et Delettrez, Ancienne collection Paul-Louis Weiller – Vente IV Livres, Autographes et Manuscrits, 5,6,7 et 8 april 2011, lot 684. https://www.gros-delettrez.com/lot/9489/1759611-jean-benjamin-de-laborde-1734-1794-compositeur-de-musique-il?search=chansons&sort=num&

[64] Lot essay, lot 684, https://www.gros-delettrez.com/lot/9489/1759611-jean-benjamin-de-laborde-1734-1794-compositeur-de-musique-il?search=chansons&sort=num&. Even this copy, though, had seen better days in the sale room. As the same lot text makes clear, it was sold in 1930 for 30000 francs, which if we use the gold equivalent basis is something like 60000 Euros today

[65] For discussion of the phrase merle blanc with examples, see the online version of the Dictionnaire Littré, https://www.littre.org/definition/merle