One of the remarkable aesthetic features of the Choix de Chansons was that it was entirely engraved, meaning that no moveable type was used. The musical notation, words and images were all created by burin engravers.1 In the case of the text and music, this was achieved by artisans in the very specialized metier of music engraving. It was a field in which French engravers had, by the time of the songbook, established pre-eminence.

It is natural that the skill and invention of the image engravers, particularly Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune, has captured most attention amongst scholars and connoisseurs of the Choix de chansons. However, this essay will dwell on the elegant and consistent music engraving in the work, and on its creators, two renowned music engravers, François Moria and Marie-Charlotte Vendôme, collaborators, business partners and then briefly husband and wife. Mlle Vendôme is of particular interest, both because of the length of her career and pre-eminence, and because she was in the eyes of many scholars, first among equals in a speciality that over the course of the century became the province of several very skilled women engravers. It is worth reflecting that while the music, text and images of the Choix de Chansons are the work almost exclusively of male artists, the engraving of the music is in large part due to one of the more remarkable female artist-artisans of the later eighteenth-century, whose style is one of the ‘constants’ of the songbook.

Elegance and Expediency – the Growth of Music Engraving

The history of music printing parallels, unsurprisingly, the growth of text printing from woodblock in the late fifteenth century to moveable music type in the wake of Gutenberg.2 However, the complex and error-prone methods of wood based moving type proved inadequate to the task of increasingly complex musical manuscripts, and soon ceded place to a more specialist but more reliable, regular, detailed, and clear method. This was intaglio engraving on plates of copper, or more frequently, pewter, a cheaper if less hard-wearing alternative. Music engraving developed a range of its own tools, techniques and specialists.3 Although many of the techniques of music engraving resembled those of burin engraving for images, many specialist tools were developed to enable stave lines to be marked, note heads and later clefs, to be precisely marked and clear and unambiguous markings to be visible to musicians often needing to see the score in difficult light conditions. This was a time-consuming and skilled process, and the effort was increased in the case of lengthy opera scores in which music and text need engraving in reverse and freehand, and in complex and demanding instrumental scores with increasing specificity and variety of marks, lines and other details that required capture. Fournier’s theoretical contribution on engraving to the Receuil des Planches… (the companion project to the Encyclopédie), included precious details and summaries of the music engravers art, with its music engraving example engraved by “Madame de Lusse,” showing, for example, the newly developed specialist tools and punches (poinçons), for engraving clefs (Fig 1).4

Although lithography, photographic, and digital methods have long taken over, copper-plate music engraving survived in certain specialist pockets in the music publishing trade right the way through to the late twentieth century and continues as a specialist practice today, in the German company G. Henle Verlag.5

The complex regulation of printed matter in ancien-régime France was a network of monopolies and privileges, which affected the typographic (letter press) publication of music—a monopoly essentially accorded to Ballard by Henry IV and maintained with some rigour by the Ballard enterprise thereafter. It was a monopoly against which Pierre-Simon Fournier famously campaigned and that was finally weakened, if not entirely overcome, in 1764.6 But after the “arrêt de Saint-Jean de Luz” of 1660, music engraving, along with other types of engraving, escaped this monopoly. It remained subject to other rules of librarie including permissions and approbations, but it was free of Ballard’s stranglehold, of the cumbersome and restrictive practices of the “Maîtrise,” and others of those monopolistic practices that dogged those, including Fournier, who wished to innovate in moving type music printing bodies.7 This allowed enterprising specialist engravers to begin to make a career producing clear and easily reproducible scores to feed the increasing market for music to play and share not only in professional but also in domestic settings. There was no obligatory workshop structure, so while technical expertise in music engraving was sometimes passed down via apprenticeships in workshops, the space of burin engraving was a relatively ‘free’ one to enter and train.

If music engraving was one answer to a movable-type publishing privilege, it was also a practice that began to modify the other very important way music circulated in early modern Europe—that is, in hand-copied manuscripts of scores and parts of scores. Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued in the entry “Copiste” in his Dictionnaire de Musique in 1768 that the traditional hand-copy was more accurate, flexible and practical than any other method including engraving.8 However, even as he made this argument, practice in the era of the Choix de Chansons—the decades of the 1760s and 1770s—demonstrated the opposite. Engraving was flexible, precise, accurate, and less onerous than hand-copy. When Nicolas Framéry later in the century edited the Pancoucke Encyclopédie Methodique he reopened the debate by reprinting Rousseau’s “Copiste” but inserting a counterargument by Pierre-Louis Ginguené arguing for the all-round superiority of engraving.9 Framéry’s later entry in the same dictionary, “Gravée,” summed up his view of music engraving’s utility:

Engraving has some great advantages over movable type printing. It is much neater and easier on the eye. It even has some advantages over hand-copy, in that it is more regular and even. When carried out by a skilled artist it is more regular in its forms. It can also be completely error-free because those mistakes that escape a first proof can be easily corrected, and, lastly, once a plate is made, as many copies can be made as are required.10

The Pre-eminence of Women Music Engravers

Framéry seemed to recognize the prominence of women in the specialist role of music engraving in his entry title “Graveur, Graveuse” (701), giving a rare feminine form to the word. This was perhaps because by the time of his article a considerable number of women specialists had made their mark in the French music engraving trade including Mlle Noël and Louise Roussel, and Mme de Lusse. As Fau Verry explores, the first woman music engraver known to scholarship is Louise Roussel in 1723.11 By the end of the century, women outnumbered men in the profession, engraving roughly 55% of all scores, though the “Professional” class of woman engravers (those with long careers and independent finances) was probably more like 27% of all music engravers. Marie-Charlotte Vendôme was not unique, but one standout among a group of very skilled women engravers to whom music engraving offered a specialist and lengthy career. Framéry further points out that customary practice involved teams, one engraver the job of the notes (with the specialist implements and punches needed) and another principally dedicated to ‘la lettre,’ a more freehand burin task which might include slurs, ornamentation and lettering as well as title pages and longer texts. It may well be that this is how François Moria and Mlle Vendôme carved up the tasks. But the evidence of the many scores engraved solely by Mlle Vendôme early in her career as well as those made entirely by Moria would point to their both being capable across the range of tasks rather than systematically dividing their work on the Choix de Chansons into specific tasks.

The social background and networks of music engravers were explored by Fau Verry based on systematic study of marriage contracts of engravers, and she concluded that many music engravers, men and women, emerged from artisan and merchant milieux, and intermarried in their own demographic and networks, “la petite bourgeoisie laborieuse,” not straying far in terms of social ascent or descent.12 However, as the eighteenth century wore on, “Les épouses de musiciens gravent la musique de plus en plus.”13 Musician/engraver partnerships, Fau Verry argues, usually saw the wife of an established musician ‘take up’ the profession.14 She does offer one more interesting example which saw a skilled woman engraver marry and then engage with her husbands’ musical career—the remarkable partnership of Louise Roussel and Jean-Marie Leclair, the violinist. But even among those examples, the circumstances of Marie-Charlotte Vendôme’s partnership with Moria remain unique and indeed, to an extent mysterious. Moria was a musician and maître de musique before he became a music engraver and publisher, but his marriage to Mlle Vendôme happened only after she had become a pre-eminent engraver and had already enjoyed a long career and, we presume, friendship with him. Financially, as Fau Verry so thoroughly documents, Mlle Vendôme was one of the “Professionelles,” those who had already established a major reputation before her marriage, a union to which she contributed disproportionately (in financial terms) as discussed below.

François Moria

In a sense, the continuing ambiguities, and lacunae in the biographies of both Moria and Vendôme attest to the ways in which both their lives as artisans and their specialist skills have been overlooked or at least, under-ranked in the estimation of scholars and historians. To the best of our knowledge, we can say that François Moria, musician, maître de musique and later engraver and publisher, was born around 1720, was married three times, first to Marguerite Ducuir, then Marie-Laurence Trianon, then for a third time in his fifties in 1775 (just a year or so before his death) to his partner in engraving, Marie-Charlotte Vendôme. He had five surviving children by his two previous marriages, including two sons, also named François, one from each marriage, who both became musicians.15 This led George Cucuel to point out: “L’on peut s’imaginer les complications de l’Etat civil et la difficulté des recherches généalogiques, si l’on songe qu’à la même époque il y avait dans la même maison trois François Moria, tous trois musiciens !”16 It is indeed complex to untangle the web of Moria’s multigenerational relations, but it remains of interest that Moria’s family were deeply involved in all aspects of music and music making throughout the moment of the Choix de Chansons and perhaps this might have given him greater understanding of, and sympathy for, Laborde’s ambitions in the songbook, and professional ties to Laborde as a musician. We know little of how our François Moria (senior) changed his path from musician and music teacher to music engraver and publisher. While some scores from the 1750s identify him as a music engraver, others refer to him as ‘éditeur,’ i.e. the publisher and seller, with premises on the Rue des Fosses Saint-Germain next to the (then) Comédie Francaise. This clearly became one of the familiar ‘addresses’ for those seeking to buy music, but was not, it seems, a lucrative enterprise for Moria. Opting, it seems, for the life of a music entrepreneur, Moria shared some of the financial precarity that Robert Wellington describes affecting Jean-Benjamin Laborde in his essay on this site on the “Prospectus” for the Songbook – but at his far less exalted social and financial status, this precarity was more biting. One can even speculate that the Choix de Chansons was a very costly and perhaps even ruinous project for him in terms of his time and lost potential business from other clients. At his marriage to Marie-Charlotte Vendôme, in 1775, Moria had 700 livres in current debts, but these were offset by 1500 livres supplied to him by Vendôme.17 Moria died in 1776, at which point his business was in debt, his net worth even more reduced, he was subletting his lodgings and renting his clothes and linen.18 Consequently his debtors moved in, Vendôme renounced her rights to succession, and his sons who did not deign to be present for the witnessing and signing of his death inventory, also renounced.19

Before this rather ignominious end, François Moria’s involvement with Laborde’s musical output, and specifically his songs, was deep and long-lasting. From the 1750s, he engraved and published at least 6 collections of Laborde’s Chansons set for voice, with accompaniment on Moria’s instrument, the violin and basso continuo.20 And it is significant that among these scores are the first we know that Mlle Vendôme produced for Moria’s publishing enterprise. Moria engraved and published the first collection in his own name, but the deuxième receuil, published in 1757, was engraved by Mlle Vendôme.21 This date seems to mark the beginning of the long working relationship between Moria and Vendôme, for which we might even argue that Laborde’s music was one catalyst.

Marie-Charlotte Vendôme

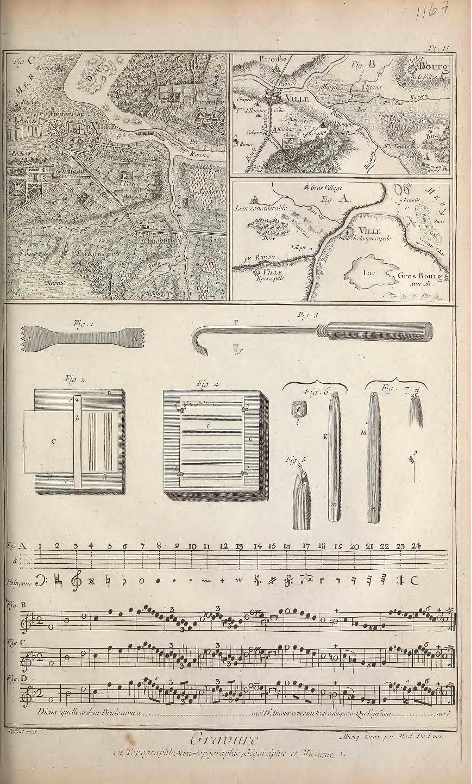

His partner on Laborde’s deuxième receuil, and on a host of other scores right up until the Choix de Chansons project, Marie-Charlotte Vendôme, is one of the most important figures in music engraving of the eighteenth-century. She was born around 1732 (at her 1782 second marriage her age was given as “Environ cinquante ans”) into a family of upper-artisan status.22 Her parents were Marcelin Vandôme, a maître-tapissier, and his wife Rénée Gueraud, [both names subject to the variants of spelling common in the eighteenth-century]. Thus, she came from what might be called skilled-artisan roots, and she probably worked at first from the family home on the Rue Saint-Jacques, where she was one of three surviving sisters.23 Quite how Marie-Charlotte became involved in music engraving has been unclear to scholars. My argument in this article, based on some new archival evidence, is that she may have learned from and with her older sister, Marguerite Vendôme. I contend that it was Marguerite who, on marriage to Jacques-Adrian DeLusse, the musician, became known first as “Mme Vendôme” and then as “Mme Delusse (or De Lusse).” Thus, Marguerite Vendôme is the engraver of the illustration in the planches discussed earlier and the Madame De Lusse who has remained otherwise obscure to scholarship though her production is well known in the 1760s and 1770s.24 We do know that Marguerite Vendôme would not have used the title “Mlle” after 1753. We should now re-attribute scores engraved before the mid 1740s to Marguerite, and we can’t now be sure whether any score signed “Mlle Vendôme” between this time and 1753 is by Marguerite or Marie-Charlotte. This would be the case with this marvellous but irregularly spaced title page of the score for Fouquet’s Les caractères de la paix in 1752 (Fig 2), with its splendid title page with hand-engraved flourishes on the name, and a real sense of occasion.

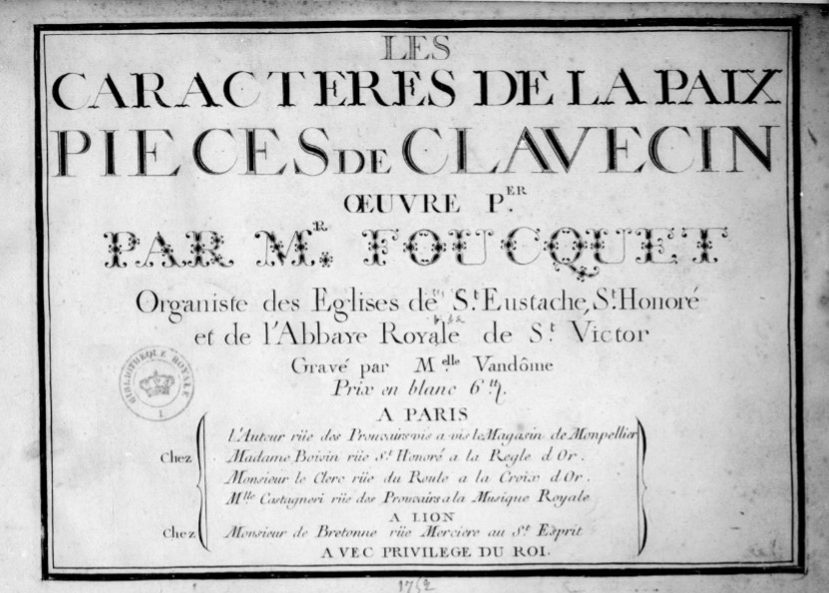

By 1753, though, we can be more certain that Marie-Charlotte is “Mlle Vendôme,” including on this contribution (the first fifty pages) to the engraving of the music for Rousseau’s celebrated Le Devin au Village in 1753 (Fig 3).25

Thereafter, Marie-Charlotte Vendôme (still spelling her name with an ‘a’ at this point) was clearly busy and sought-after, especially for music and text settings, such as Philidor’s mini-cantata l’Eté in 1755.26 By the end of the decade, she enjoyed a high reputation. An article in the Année Littéraire in 1759 notes Mlle Vendôme as “cette célèbre graveuse de musique.”27

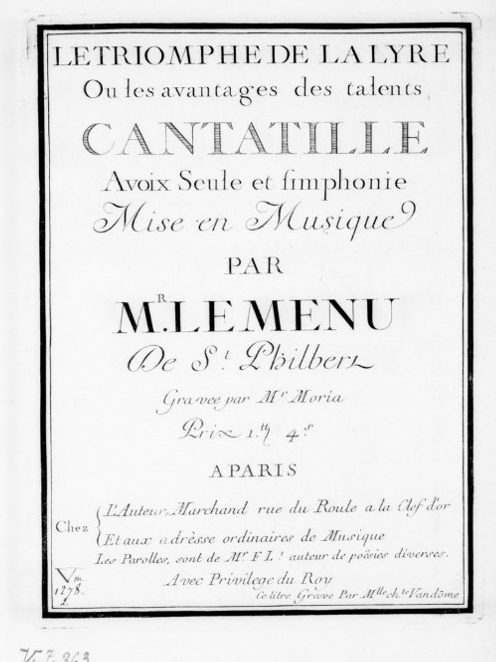

We might certainly ask how and why Moria, an engraver himself, came to seek out and rely more and more on his prodigious and talented collaborator. Fau Verry and others consider Moria to be an inferior engraver, only “assez habile,” but this seems a little unjust a judgement when one looks across a range of his output, and he certainly was both competent and busy in the 1750s.28 There is no doubt that Mlle Vendôme had already proved herself an exceptional talent by the late 1750s and perhaps Moria felt himself in need of superior, or more particular skills to meet new demands for both quantity and quality. One title page of a score of Christophe Le Menu de Saint Philibert’s Le Triomphe de la Lyre in 1761 might hint at an answer (Fig 4). While it has François Moria named as an engraver, we note the detail at bottom left: “Ce titre gravé par Mlle Chte Vandôme.”29 This may be an early hint that Moria needed the specialist freehand engraving skills of Marie Charlotte Vendôme to supplement his own talents on complex tasks, and in particular to address lettering, including title page, titles, script, numbers and other freehand elements. It also might be a rare occasion on which Marie-Charlotte Vendôme’s name is used to distinguish her from her elder sister.

While this remains speculation, this particular title page bears some hallmarks of what would become Marie-Charlotte Vendôme’s signature style, including the flourish and variety of the fonts and layout, sometimes fancifully contrasted (as in the two parts of Le Menu de St Philibert’s name). The attractive and dynamic general effect is, however, also marked by grammatical inconsistencies and ‘freedoms’ in orthographic issues (spacing issues, misuse of accents and noun-adjective agreements, occasional spacing irregularities, the lack of space between A and voix on line 4, and so on) that also would be characteristic of Mlle Vendôme’s work right up to the Choix de Chansons.30

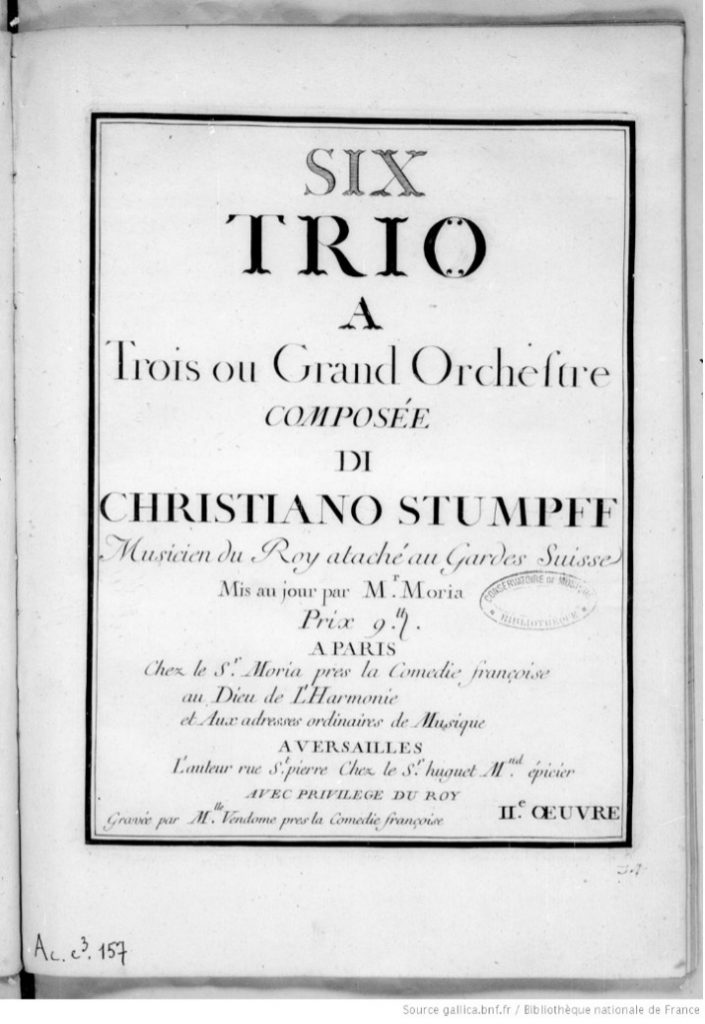

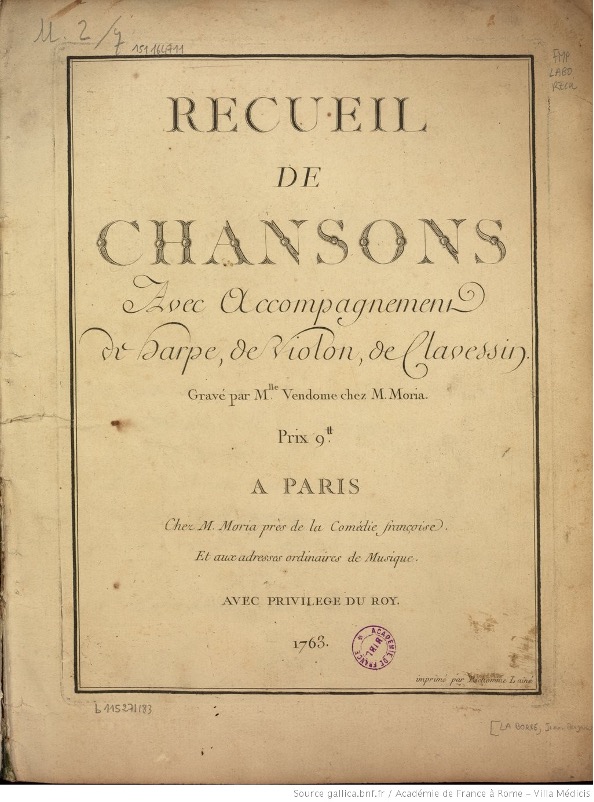

In a few short years, Marie-Charlotte Vendôme’s style seems to have become more confident, lively, and even more firmly associated with Moria’s enterprise, as this title page for the 1763 score of one set of Stumpf’s trios shows Mlle Vendôme listed as the engraver, working in Moria’s premises but acknowledged as the sole engraver of the entire work, with Moria listed as the publisher.31 By this time, Mlle Vendôme’s copperplate flourishes are more confident, and the title pages become an exhibition of mixtures of cursive and block, italicisation, and other forms of emphasis (Fig 5).

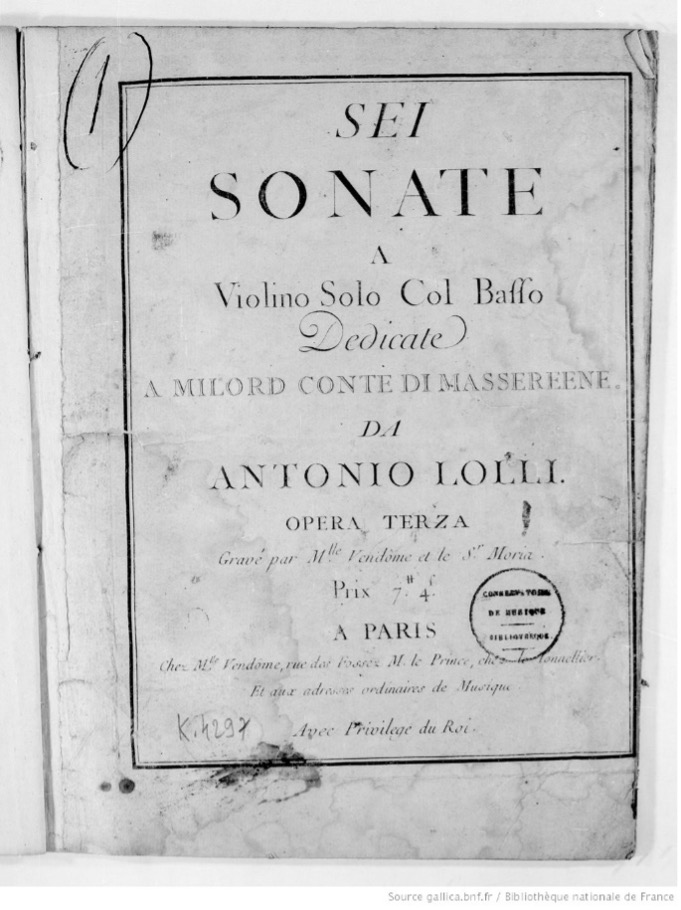

Intriguingly, in the course of the 1760s, the decade of the most intense and productive period of their collaboration, we occasionally see various other configurations of their collaboration: on the title page of Lolli’s Violin Sonatas, we read “Gravé Par Melle Vendôme et Le Sr Moria.”32 This indicates a joint endeavour led by Vendôme. The location of sale is now described as “Chez Mlle Vendôme,” (Fig 6) giving a sense of Marie-Charlotte’s primacy and centrality to Moria’s enterprise.

More certainly, and more frequently, in the mid 1760s we start to see the formulation “Gravées par Melle Vendôme, chez M. Moria,” on title pages, implying that under the aegis of Moria’s enterprise, Mlle Vendôme was chiefly responsible for the entire engraving process.33 In a more banal way it implies too that Marie-Charlotte Vendôme was living at the same address as Moria, and indeed, at their marriage in 1775, the address of both of them is given as Moria’s then address on the rue Fosses Saint-Germain. One might speculate that over and above their professional partnership, an intimate relationship, a friendship or quasi-familial relation existed between Vendôme and the extensive Moria household from the mid 1760s.34

Laborde, Moria and Vendôme

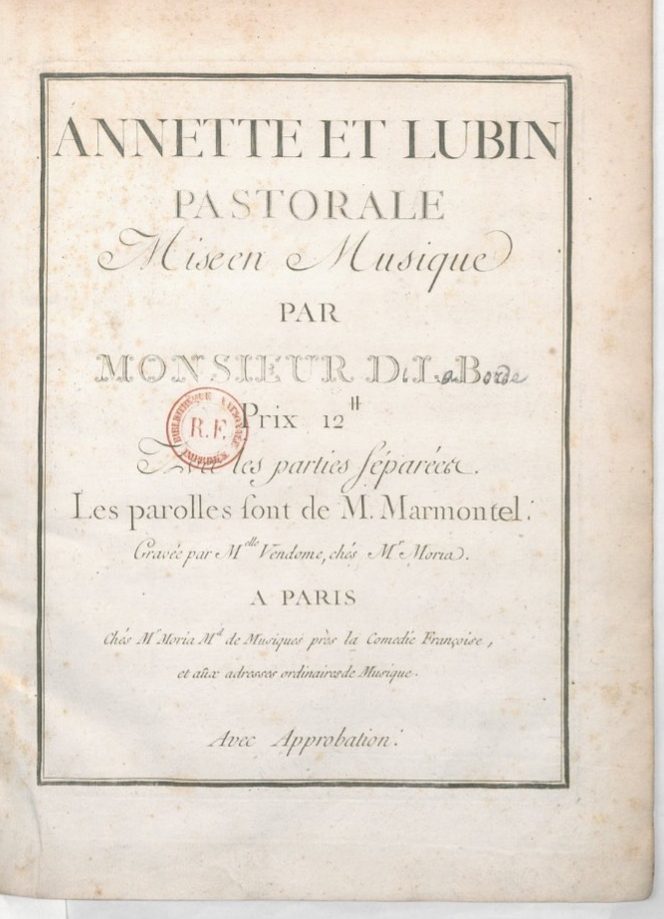

It was likely through the series of collections of songs for violin, voice, and basso continuo published in the late 1750s, that Laborde came into contact with Marie-Charlotte Vendôme and François Moria and that the pair established their working relationship with the musician and Fermier-Général. The pair became further involved with Laborde when they engraved the music for the score of his pastoral comedy, Annette et Lubin from Jean-Francois Marmontel’s freshly written version of the tale, published in 1762 (Fig 7).35 Laborde’s work was given a private performance at the Duc de Richelieu’s theatre in 1762, but was not much performed afterwards, as it suffered from emerging at the very same time as the runaway success of Charles Simon Favart and Marie Justine Favart’s Annette et Lubin, derived from the same material, on the stage of the Italiens.36 Nevertheless, the complex score of Laborde’s pastoraleis one of the largest-scale engraving enterprises in music-drama that the Moria/Vendôme partnership had taken on up to that point.

It is also worth noting that they continued to make a name as engravers of music drama thereafter, engraving notably Laborde’s own Le Chat Perdu, Monsigny and Collé’s L’Isle Sonnante and the smash hit of the late 1760s, Monsigny and Sedaine’s Le Déserteur, a complex and lengthy full score.37

However, it is another of the collaborations of Mlle Vendôme “Chez M. Moria” in 1763 (Fig 8) that is most notable in the context of our project on the Choix de Chansons:

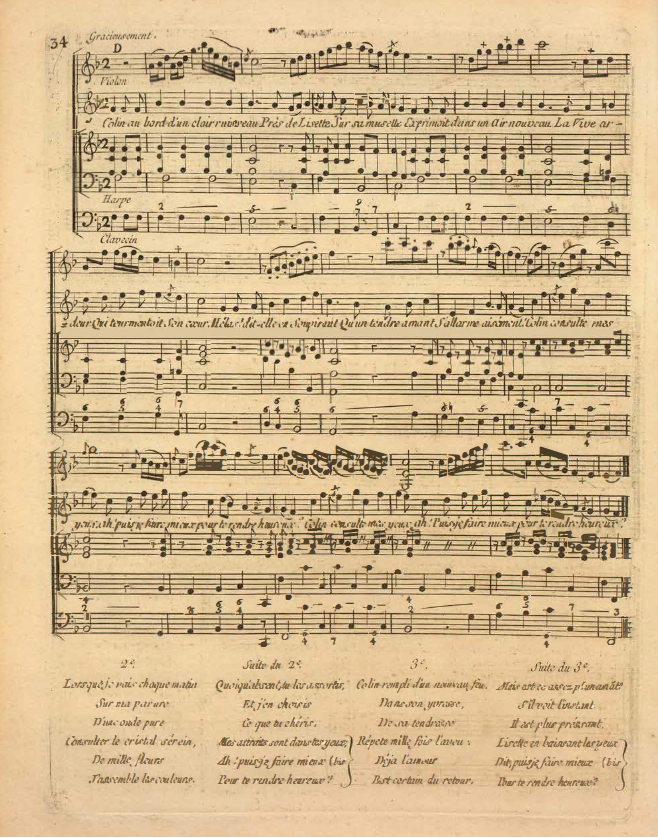

This “anonymous” collection of Chansons is by Jean-Benjamin de Laborde and contains songs and music that in some cases were re-used in the Choix de Chansons. They were scored for an unusual group of instruments which move us from the early collections of songs for voice and violin towards the scoring of the Choix de Chansons of 1773 (principally for harp and voice). Surely, this collaboration in 1763 might have sown the seeds of the later more elaborate and ambitious collaboration between Moria, Vendôme and Laborde.38 Certainly, it brought them once again into close contact with him as a musician. Incidentally the fact that it was printed by Jacques-Nicolas Richomme l’ainé, is a hint that the relations binding Moria and Vendôme with the Richomme family date from this moment. This Richomme’s son, Antoine-Jacques Richomme, the great French music engraver and publisher of the end of the century became an apprentice to Mlle Vendome in 1766, according to his notes in his Receuil d’echantillons de musique gravée of 1825.39 Given the already confident handling of complex musical notation and integration of a great deal of text both into the score lines and written out on pages facing the music, this must be regarded as a first test of Mlle Vendôme’s response to some of the challenges of the later, Choix de Chansons, though it clearly shows signs of being a less expansive and less luxurious enterprise, as this page (Fig 9) shows:

This song is one of those that, in simplified setting shorn of the complex violin part, would be included in the Choix de Chansons.This page also seems to have been following the penchant for ‘dark’ printing (a variance in the amount of ink and pressure in the actual printing process), discussed by Fau Verry as one of the ‘variations’ in fashion. By the time of “our” Choix de Chansons, we witness a lighter and more ‘distinct’ print allowing for more distinct semi-quaver lines, etc.

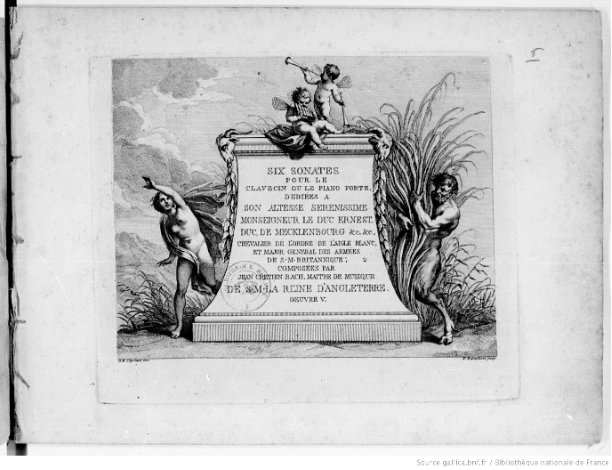

There is also some evidence that Moria and Vendôme were comfortable working with image engravers. An edition of Johan Christoph Bach’s violin sonatas engraved by the duo in the 1760s shows them working with an existing engraved title by esteemed engravers Giovanni Battista Cipriani and Francesco Bartolozzi to create the lettering and music for a French edition (Fig 10).40

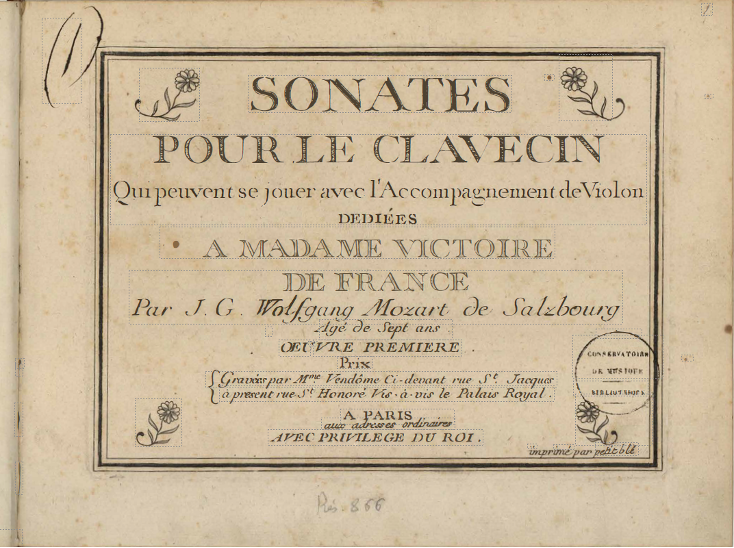

We might also speculate that the “Mme Vandomme” who engraved the first ever published work by Mozart (Fig 11), the two sonatas for harpsichord and violin (KV 6-7) in 1764 is not Marie-Charlotte, as has been widely understood, but her sister Marguerite. The latter not yet using her husband’s name but giving herself a married title and establishing herself on the newly fashionable ‘right bank.’

This might explain why there are stylistic and typographical traits we see on this score that we don’t encounter in Marie-Charlotte’s work, and the fact we do not see Marie-Charlotte’s name associated with the “Rue St Honoré” subsequently.

Moria, Vendôme and the Choix de Chansons

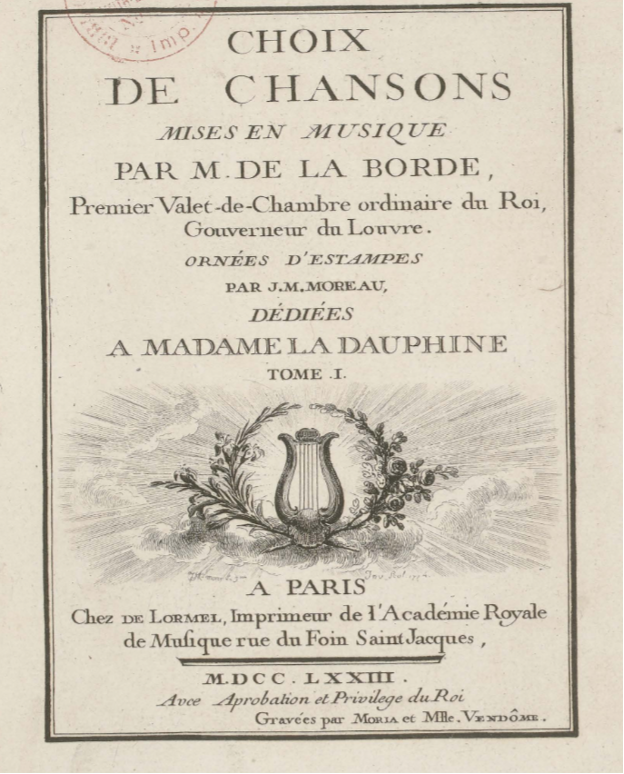

Laborde’s relations with his key image engraver, Jean-Michel Moreau, were notoriously to sour during the Choix de Chansons project, and this led to changes and inconsistencies in the quality of engravings. His trusting collaboration with Moria and Mlle Vendôme, on the other hand, remained solid throughout the four volumes of the songbook. Certainly the ‘signature’ and style of Moria and Vendôme is more present in the Choix de Chansons than that of any other engraver of any type. Their particular quirks, including the fancy song titles opposite the engravings, the various levels of text and music engraving and the mise-en-page of the songs are their distinctive and renowned handiwork, particularly that of Marie-Charlotte Vendôme. The Choix de Chansons title page (Fig 12) “Gravées par Moria et Mlle. Vendôme” indicates full collaboration, rather than Vendôme working for Moria at his premises or under his supervision. It is likely that by this time Marie-Charlotte Vendôme was the senior partner.41

The texts on this title page from the first volume hints in every way that Vendôme’s particular style and ‘tics’ were pre-eminent. Though this is disciplined, ordered and careful than the more extravagant titles of some of the couple’s earlier scores, it is to be noted that “Approbation” is misspelt, and the c and e of “avec’ are reversed. These errors are somewhat surprising given the prestige and importance of the publication. But this page would have required a particular ‘va-et-vient’ with the image engraving team to ensure the integration of visual motifs and text, and perhaps this caused the rush that led to the mistakes.

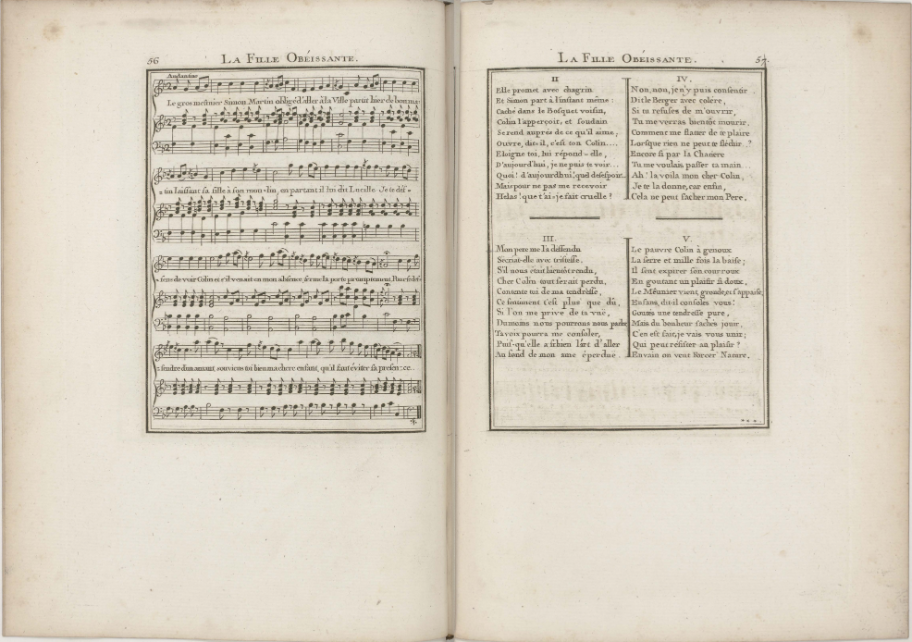

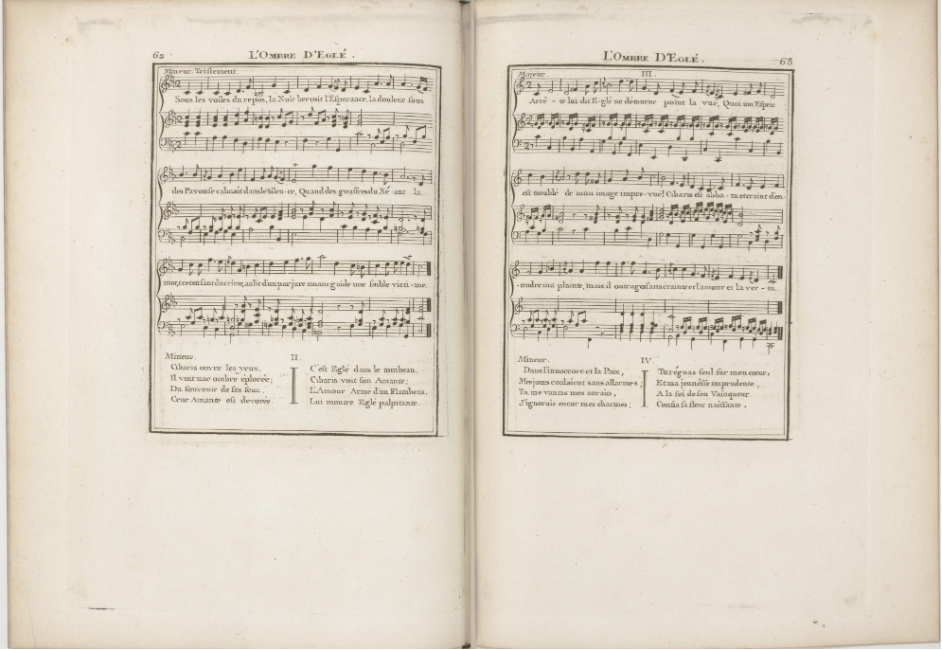

The ‘ensemble’ project of the Choix de chansons imposed specific tests on Vendôme and Moria because ‘their’ music and text blocks were standardised in size to fit the same dimensions of plate as the image engravings. Thus, the need for absolute legibility of both text and music within these relatively small spaces was even greater in comparison to other scores with larger space for staves and text and, we imagine, greater visibility for anyone actually trying to sing from the score. This we can see in the following two examples from the first volume one (Fig 13.) La Fille obéissante which takes the most familiar tactic in the songbook, writing text of the first stanza of the song into the music stave and then writing out the text of the following stanzas on a facing page. (In this page you can see how tight the fit of text to margins becomes, in the line Le Meunier vient, gronde et s’appaise in the fifth stanza, for example). Another solution adopted where songs have fewer total words, such as L’Ombre d’Eglé (Fig 14),is to try to keep texts proximate to the music stave.

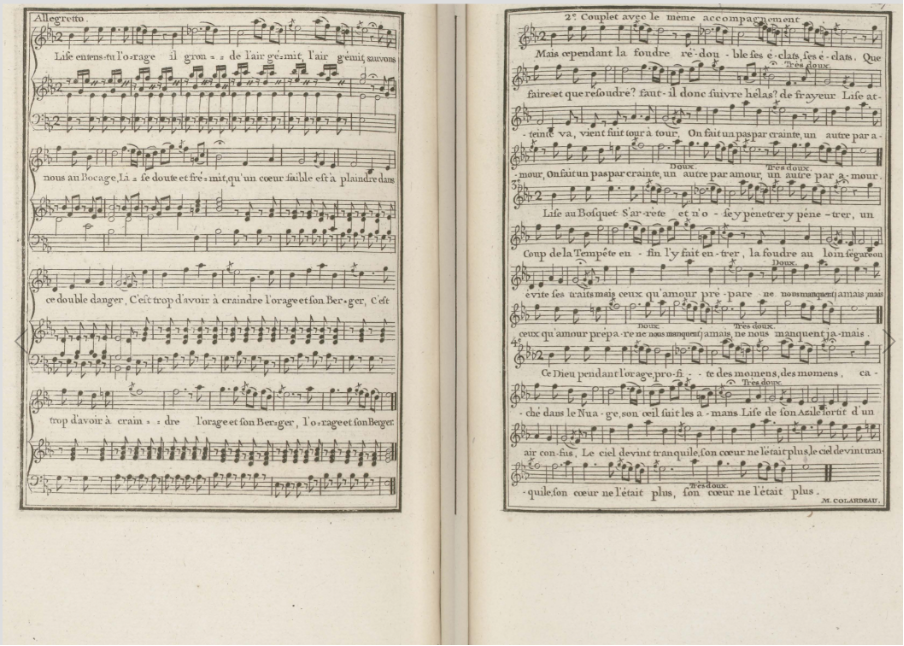

Under these constraints, Moria and Mlle Vendôme nevertheless managed to keep harmony between text and score, to imprint something like ‘energy’ in their style of engraving both music and text and add to the sense of this being a luxurious, painstaking and aesthetically pleasing whole. The clear, evenly printed and not over-darkened aspect of the music and text is testimony to Lormel’s careful printing as well as engraving of course, but some of what Fau Verry sees as the skills developed to the ‘apogée’ of music engraving by the Moria/Vendôme team is visible. Although the mammoth enterprise occasionally wearied Moria and Vendôme, evident, perhaps, in errors of orthography and occasional unclarities in music notation, in general across all the volumes there is ample evidence of Vendôme’s trademark mixture of admirable liveliness, clarity, precision and aesthetic beauty in the musical markings. At the same time, there is a busy, sometimes ‘overstuffed’ feel to the way the texts and musical notes are bunched or layered. For instance, in the example of “L’effet de la peur” (Fig 15) the engravers have to incorporate a large amount of textual and musical information, with complex alignments, multiple incidental markings, directions, and even name of the text’s author to include. This wealth of complex detail, all to be engraved in reverse, put pressure on the alignment of bar-lines in the staves, and the ‘squashed’ final minim which almost bumps into the double bar line on page one. This also perhaps led to the second page illustrated here essentially giving up on the accompaniment and giving only the singer’s line, a hybrid solution to the space problems that the format decreed by Laborde, probably on the basis of the format and size of engraved images, dictated.

We might also note how the choice of whether to place expressive markings (“Très doux” etc.), above the stave or below seems dependent on space available rather than consistent practice in page two of the song, and the last Très doux is positively shrunk to fit. Despite these constraints, one senses the confidence, consistency, and quality of the Moria-Vendôme engraving enterprise, from the basic legibility to the specifics of distinctly marked grace notes, indications of where and how to accentuate vowels, etc. Their own work was subordinate in the aesthetic hierarchy to the work of Moreau and the group of image engravers chosen to replace him across the volumes. But in the songbook volumes as a whole, their titles, staves, texts and other markings, their punches, scrapes and ruled lines are an important part of the way the songbook functions aesthetically. The relatively restrained page size cannot have been practical for anyone wishing to actually sing from the songbook, as Erin Helyard, has discussed in his essay. But the pages of music and text make their own argument for the practicality, suitability and beauty of engraved music as a viable mode of transmission and as an aesthetically pleasing genre. Elisabeth Fau Verry’s thesis asks whether music engravers were artisans or artists, and her eloquent analysis 42 points to the fact that although by social class and circumstance they were artisan, they were often of artistic dispositions and ambitions. I would argue that the work of Moria and Vendôme on this remarkable aesthetic object is a rare and enduring testament to this dual identity. It shows the tension between artisan and artist, between constraint and expression, between command and freedom, and is a showcase for specialist skills that were as precious as they were under-remunerated.

Certainly, the pressure on Moria and Mlle Vendôme must have been immense as we know that Laborde had promised and gained subscribers before he delivered and must have been in a hurry to get the engravings done. Fau Verry calculated that it must have taken over three hours work to engrave one plate of music,43 which implies that the couple (and any helpers they may have had on the project) must have invested more than one thousand hours work in the enterprise. This would certainly have meant consistent and perhaps exclusive concentration on the project at the expense of others for a significant period. Perhaps our Choix de Chansons, which was not finished on time, expanded in size and scope between prospectus and publication, not delivered as promised to its subscribers, might have contributed to Moria’s final impoverishment. There seems to be some doubt about whether even the ‘star’ image engravers were ever properly paid, so perhaps Moria never received what he was owed either. The very effort at aesthetic and artisan excellence that the songbook required probably meant the putting aside of more regular, and regularly-paying work. Moria was substantially in debt when he married Vendôme shortly after the songbook’s last volume was finally published, and in desperate straits at his death not two years later.

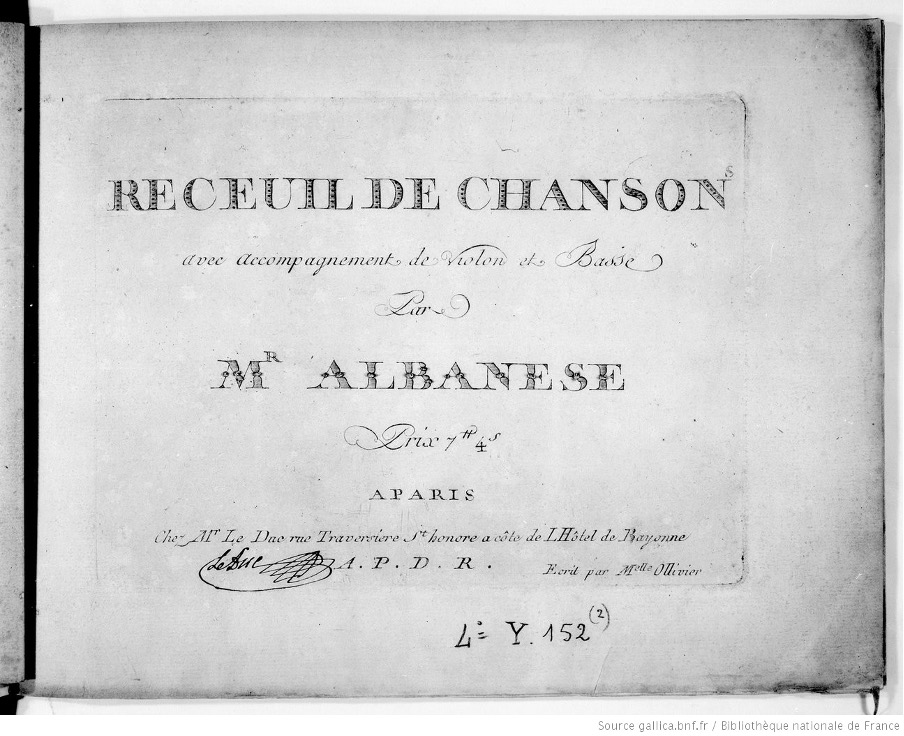

Moria and Mlle Vendome’s working partnership and brief marriage was ended by his death in 1776.44 He left Marie-Charlotte Vendôme the debts that dogged his person and his enterprise, leading to her formal renunciation of her part in his estate.45 Marie-Charlotte Vendôme continued to engrave and publish in the late 1770s and early 1780s, though much less frequently and perhaps assisted by Moria’s daughter by his second marriage, Béatrix-Françoise.46 One curious example from 1782, seems to imply she teamed up with, or trained, Mlle Olivier, a younger woman to handle the text (Fig 16).47

More certainly, Marie-Charlotte remarried, in 1782, “agée de cinquante ans environ,” in the small commune of Buc just outside Versailles. Her second husband, more than a decade younger than she, was a certain Mathieu-Jean Brichet, described in their marriage registers as a ‘bourgeois,’ and perhaps in a position to elevate Mlle Vendôme out of the precarity that dogged her partnership with Moria.48 We can identify this, her second husband, as Mathieu-Jean Brichet de Saint Quentin, commis aux recettes générales des finances and later a violent revolutionary Jacobin and section leader, described as an “Enragé Maratiste,” who fell out of favour in the last years of the terror and was guillotined on 9 July 1794.49 One can only speculate on whether and how Marie-Charlotte Vendôme shared or endured the passions, commitments and violent changes of fortune of her second husband. But we should note that Vendôme, a ‘Widow of the Guillotine,’ got married for a third time to Jacques Vincent Bougeart in July 1795. However, her subsequent life and the date of her death remain obscure.50

As the eighteenth-century ended, the long professional trail of Marie-Charlotte Vendôme petered out. In a way, her fate mirrors the situation of French music engraving at the end of the century. Historians note that the rising cost of paper and other constraints of time and material, as well as new competition from liberated moving-type printing led to French music engraving beginning to lose its pre-eminence the 1780s despite the excellence of individual engravers in the revolutionary decades such as A-J. Richomme.51 All the more important, therefore, to celebrate the apogee of Moria and Vendôme’s collaboration on this uniquely ambitious and luxurious project. The Choix de Chansons, however ruinous it might have proved to many involved in it, represented one high point of that ambitious and aesthetically beautiful craftsmanship which as Anik Devreis-Lesure claims “…enabled France to dominate the eighteenth-century music market.” 52

Mark Ledbury, 2022

1. For a useful and visually rich summary of engraving techniques see the Metropolitan Museum website, “Engraving,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed May 6, 2022, https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/drawings-and-prints/materials-and-techniques/printmaking/engraving.

2. For a venerable but still useful summary of the development of musical notation and printing, See Henri Robert, Traite de gravure de musique sur planches d’etain et des divers procedes de simili gravure de musique ([Paris], 1926). A more recent round-up of the history of music printing techniques may also be found at the website https://musicprintinghistory.org/ created and maintained by Rosendo Reyna.

3. The most through and well-documented study of music engraving in all its aspects, technical, social and aesthetic, in eighteenth-century France, is the unpublished thesis by Elisabeth Fau Verry, La Gravure de Musique à Paris Des Origines à La Révolution (1660-1789 ), Ecole nationale des Chartes, Paris : 2 vols 1977-1978. Given the particular attention accorded to the work of Marie-Charlotte Vendôme in Fau Verry’s thesis, and its unique and enduring value to all who study music engraving, I shall cite it frequently with the short form Fau Verry, followed by volume and page numbers. I am very grateful to Julia Doe of Columbia University for her kind and thoughtful reading of this article in manuscript form, and to both her and to Madame Viviane Niaux, librarian at the Centre de Musique Baroque, Versailles, for facilitating my access to Fau Verry’s thesis.

4. Denis Diderot, Jean Le Rond d’Alembert, and Robert Bénard, Recueil de Planches, Sur Les Sciences, Les Arts Libéraux, et Les Arts Méchaniques : Avec Leur Explication …, vol. 5 (A Paris : Chez Briasson … David … Le Breton … Durand …, 1762), « Gravure en Lettres, en Géographie et en Musique », np. And plates I-III (see fig). See also Fau Verry, 303-306 , on the development of specialist ‘poinçons’ (punches) of various sizes so that more notes, accidentals and signs could be created regularly by specialist punches rather than freehand.

5. https://www.henle.de/en/about-us/music-engraving/

6. Pierre-Simon Fournier, Manuel Typographique,… Par Fournier Le Jeune. Tome 1, 1764, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1070584h, see ‘avertissement’, xxvii-xxxii, and Augustin Lottin Catalogue Chronologique Des Libraires et Des Libraires-Imprimeurs de Paris ( Paris : 1789, repr.Amsterdam: B. R. Gruner, 1969).

7. Fau Verry, I, 75-8 . See also on the techniques of engraving and publishing, the excellent survey essay by Anik Devriès-Lesure, “Technological Aspects”, in Rudolf Rasch, Music Publishing in Europe 1600-1900: Concepts and Issues Bibliography (Berlin:BWV, 2005), 63-88; Hans Lenneberg and Ralph P. Locke, On the Publishing and Dissemination of Music, 1500-1850 (Pendragon Press, 2003); Anik Devriès-Lesure, Dictionnaire des éditeurs de musique français, Archives de l’édition musicale française ; t. 4 (Genève: Minkoff, 1979):Donald William Krummel, The Literature of Music Bibliography : An Account of the Writings on the History of Music Printing & Publishing (Berkeley, CA. : Fallen Leaf Press, 1992). The text of Ballard’s privilège is printed and analysed in Brenet, Michel. “La Librairie Musicale En France de 1653 à 1790, d’après Les Registres de Privilèges.” Sammelbände Der Internationalen Musikgesellschaft 8, no. 3 (1907): 401–66. Fau Verry, I, 71-2, cites in entirety the «Arrêt” that freed engraving in 1660 and discusses the ways engravers lobbied to keep their relative freedom (1, 73-7 and sq.)

8. Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Dictionnaire de Musique , (Paris, 1768), art. « Copiste », 123-131. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k850406b.

9. Nicolas-Étienne Framery, (ed), Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Pierre-Louis Ginguené, Encyclopedie Méthodique. Musique. T. 1, 1791, art. Copiste, 369-377 https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k54053365

10. Ibid., art GRAVEE, 699. « La gravure a de grands avantages sur l’impression en caractères mobiles; elle est infiniment plus nette et plus agréable à l’œil… elle en a même sur l’écriture à la main, en ce qu’elle plus égale ; qu’exécutée ordinairement par un artiste habile, elle est plus régulière dans ses formes ; qu’elle peut être absolument exempte de fautes, puisqu’on y peut corriger aisément celles qui auraient échappé au premier examen , et qu’enfin , une fois la planche faite , on en peut multiplier les copies à peu près autant que l’on veut » (My trans.) See also the article “Gravure en Musique” that follows, 699-701. In her kind observations on the current article, Julia Doe pointed out that the idea expressed by Ginguené that music engraving eliminated mistakes is alas, a fantasy as music scholarship continues to discover.

11. Fau Verry, I, 94-104.

12. Fau Verry, I, 20-21

13. Fau Verry, 1, 22

14. Ibid. 1,22.

15. For a summary of Moria’s life and complex multi-family network see Fau Verry, II, 49-50 and family tree no 7, II, 74.

16. Georges Cucuel, ‘Notes Sur Quelques Musiciens, Luthiers, Éditeurs et Graveurs de Musique Au XVIIIe Siècle. Première Série’, Sammelbände Der Internationalen Musikgesellschaft 14, no. 2 (1913): 243–52 [248]

17. AN, Minutier Central, ET/CXXII/ 787, Marriage of François Moria and Marie-Charlotte Vendôme, 26 February, 1775, fol.2. I am very grateful to Julia Doe of Columbia University for her knowledge and advice and for sharing the original document with me. See also Fau Verry, II, 125-6 (document 26).

18. AN, MC ET/CXII/788, « Bail de Meubles à François Moria », 22 March 1775, in Fau Verry, II, 127 (document 27)

19. Inventaire Après Décès, AN., MC/ET/XXVII/386, 17 décembre 1776. I am grateful once again to Julia Doe for sharing her images of the original archival document with me. The document and its estimations of value are a sad reflection on his reduced material circumstances, and those of Mlle Vendôme his wife, subletting rooms from a pâtissier, M. Colas, in a house known as the Hôtel de Chaumont on the Rue de Seine. (fol.2)The document makes clear that for the purposes of the inventory, the brother of Moria’s second wife, Joseph Trianon, was hastily sworn in as tutor to Béatrix-Françoise Moria, the then still minor daughter of Moria by his second wife, Marie-Laurence Trianon. However, in another document, confirming the status of the inventory, Archives Nationales AN Y5286 (February 8, 1777) Marie-Charlotte Vendôme features not only as Moria’s widow but also as tutrice of the “Béatrix Françoise Moria sa fille mineure.”

Perhaps we might conclude from this that Marie-Charlotte Vendôme assumed these duties as tutor, (Cucuel implies that Béatrix-Françoise is Vendôme’s daughter, but this is disproved by other archival documents) and it is perhaps Béatrix-Françoise who becomes the “Mlle Vendome” on scores engraved in the 1780s. This does not seem unlikely but must remain speculative, and perhaps a daughter of Marguerite Vendome, one of Marie-Charlotte’s sisters, might also be a candidate.

20. These collections first emerge c.1756 though dates are not always given on title pages. See Anon., [Jean-Benjamin de Laborde], Premier Recueil de Chansons avec un accompagnement de violon et la basse continue (A Paris: chez Mr Moria, n.d.).

21. Jean-Benjamin de Laborde, Deuxième recueil de chansons avec un accompagnement de violon et la basse continue…. Gravé par Melle Vendôme (Paris: Moria, 1757).

22. Archives des Yvelines, Commune de Buc, 1MI-EC 7 (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures), 26 November 1782.

23. See Fau Verry, 22 and sq. on the family networks and social status of music engravers. For the family home of Marcelin Vandôme, see Archives Nationales, Y4751A, 01/04/1752, where he is described as living “Rue St Jacques Paroisse St Benoît,”(i.e, Saint-Benoît-le-Bétourné). Once again, the most substantial writing on Marie-Charlotte Vendôme’s career and output remains Fau Verry, esp. 308-312 where she gives a list of Vendôme’s prodigious output that she recognizes as incomplete. However, this essay adds some significant new information to her biography and allows us to correct certain facts and adjust that output. Research into the early life of Mlle Vendôme and into her family origins remains patchy and Fau Verry admitted that biographical details for Marie-Charlotte Vendôme were hard to make concrete -see her very basic ‘family tree’ of Marie-Charlotte Vendôme, which gives few certain dates and makes no mention of her marriages subsequent to that with Moria, II: 78. In this article I have argued that her elder sister, Marguerite, was married to the musician Jacques Martin Delusse, on 5 March, 1753 (Archives De Paris , archival transcriptions of “etat-civil”, V8E25, Musiciens), see below, n.21, and is the “Madame De Lusse” known to scholarship, but only vaguely documented (See Fau Verry, II, 45). We must also add another sister, Marie-Renée Vendôme, a seamstress, who married Martin Le Lièvre in Versailles in 1783, shortly after Marie-Charlotte’s second marriage. See the record in the marriage registers, Archives des Yvelines, 4E 3547, 24 February, 1783 (we know this is a sister because the father and mother’s names are recorded- Marcellin Vandome and Renée Geraud). The implications of my dating of Mlle Vendôme’s birth to 1732 or thereabouts, is that it is unlikely that she, Marie-Charlotte Vendôme, engraved any music professionally before say, the mid 1740s, and I suspect that only from 1747 or 1748 can we assume that she was active as a professional engraver. See below n.21 for further discussion. I believe we might also speculate that later (post 1775) iterations of “Madame Vendôme et Mlle Vendôme” are in fact Marie-Charlotte (taking the title, Madame, after her marriage) and her adopted step-daughter Beatrix-Françoise Moria, mineure daughter of the second wife of François Moria, or perhaps her niece, a daughter of her older sister, Marguerite Vendôme (see below).

24. Archives de Paris, (reconstructions), V8E25 “Musiciens,” Marriage of Marguerite [de] Vendôme and Jacques-Martin DeLusse, 5 March 1753. This wedding took place at the local parish church of the Vandôme family, (St Benoit), and the spouse, and the witnesses were Christophe Delusse (Brother) and Jacques Delusse, (uncle). Although we cannot be absolutely certain that this is “the” Marguerite Vendôme, because no parents’ names of the spouse are given in this record, the Parish, the year and the networks all point to this being the case. The ages are given in this summary as 28 for Delusse and 29 for Marguerite, which would put her birth year at c.1724, making her eight years Marie-Charlotte’s senior. Thus, I believe we should identify Mlle Vendôme on scores of the 1740s with Marguerite Vendôme who, on her marriage to De Lusse became either Madame Vendôme or Madame de Lusse.

25. Jean-Jacques Rousseau Le Devin Du Village, Représenté à Fontainebleau Devant Leurs Majestés Les 18 et 24 Octobre 1752 et à Paris Par l’Académie Royale de Musique Le 1er Mars 1753 Par J.J. Rousseau ( Paris: Mme Boivin, 1753). https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8452564q On the complex history of this work, see Robinson, Philip E.J. “Devin du village, Le.” Grove Music Online. 2002; Accessed 27 Feb. 2022.

26. François-André Philidor, L’Eté, cantatille à voix seule avec simphonie, deux violons, un alto et basse… On peut ce passer de la partie de l’alto en cas de besoin…, gravée par Melle Vendôme (Paris: l’auteur..1755), http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9064117t.

27. L’Année littéraire ou Suite des lettres sur quelques écrits de ce temps , Année 1759, 191.

28. (Fau Verry, 328)

29. Christophe Le Menu de Saint-Philbert, Le Triomphe de La Lyre Ou Les Avantages Des Talents, Cantatille à Voix Seule et Simphonie…, Gravée Par M. Moria…’, musical_score, Gallica, 1761, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9064075x.

30. I would once again like to acknowledge the pioneering role of Elisabeth Fau Verry in identifying aesthetic and stylistic traits of music engravers’ work. Her remarks on Marie-Charlotte’s particular style are illuminating and important.

31. Johann Christian Stumpf, ‘Six Trio a Trois Grand Orchestre…, Mis Au Jour Par M. Moria…. IIe Oeuvre’, musical_score, Gallica, 1763, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9066354d.

32. Antonio Lolli, ‘Sei Sonate a Violino Solo Col Basso… Opera Terza. Gravé Par Melle Vendôme et Le Sr Moria’, musical_score, Gallica, 1768, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9079820j.

33. See for example the elaborate title page of Johann Schobert, Sonates En Trio Pour Le Clavecin Avec Accompagnement de Violon et Basse Ad Libitum… Gallica, 1765, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9010082f.

34. Archives Nationales, MC_ET_CXXII_787 (Mariage Moria/Vendôme), fol.1. Both parties reside « Rue des Fosses Saint-Germain des Près », which is Moria’s business address. The absence of any one of Moria’s children, the small party of mutual friends as witnesses, also make this an unusual document. My entirely speculative conclusion is that the nature of Moria and Vendôme’s relationship way have been intimate from an early date and that this proved problematic for others of Moria’s kin.

35. Jean-Benjamin de Laborde, Annette et Lubin, Pastorale Mise En Musique…. Les Parolles Sont de M. Marmontel. Gravée Par Melle Vendôme, Ches M. Moria’, musical_score, Gallica, 1762, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1165227z. For a rather scathing but archivally documented discussion of Laborde’s work for the musical theatre see Couty, Jean-Benjamin De Laborde , 51-86

36. On the Favarts’ version see especially the critical edition, Blaise et al., eds., Annette et Lubin: comédie en un acte en vers, mêlée d’ariettes et de vaudevilles, Opera : Spektrum des europäischen Musiktheaters in Einzeleditionen 2 (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2016).

37. Jean-Benjamin de Laborde, Le Chat perdu, opéra-comique en un acte et en prose mêlé d’ariettes…, gravée par Melle Vendôme et le sr Moria… (Paris and Lyon, 1769) ; Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny, L’Isle Sonnante, Opéra-Comique En 3 Actes Représentée Pour La Première Fois Par Les Comédiens Italiens Ordinaires Du Roy Le Lundi 4 Janvier 1768, [Paroles de Collé]…. Gravé Par Melle Vendôme et Le Sr Moria’, (Paris , 1768), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k11650404; Monsigny and Sedaine, Le Déserteur, Drame En 3 Actes, Représenté Par Les Comédiens Italiens Ordinaires Du Roy Le 6 Mars 1769. Gravé Par Melle Vendôme et Le Sr Moria’, Paris, 1769, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k8591858.

38. Jean-Benjamin de Laborde, ‘Recueil de Chansons Avec Accompagnement de Harpe, de Violon, de Clavessin.. Gravé Par Melle Vendôme, Chez M. Moria…’, (Paris , 1763), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k91167278.

39. Cited by Fau Verry, II, 58-9. I have been unable to locate a copy of this source.

40. Bach, “Six Sonates Pour Le Clavecin Ou Le Piano-Forte… Oeuvre V. Gravées Par Mlle Vendôme et Le Sr Moria.” https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9010249h

41. Fau Verry, I: 328-9, claims that Moria was essentially Mlle Vendôme’s “apprentice”, though this is figuratively meant. I prefer to see this as a closer partnership, one perhaps ‘led’ by Marie-Charlotte Vendôme but one in which the pair found ways of ensuring effective and productive collaboration.

42. Fau Verry, 1: 122-4

43. Fau Verry, I: 86

44. For his inventaire see AN. MC/ET/XXVII/386 and Cucuel, op.cit.

45. Archives Nationales, MC/ET/XXVII/387 « Renonciation par Marie Charlotte VENDÔME, à la communauté de biens établie entre elle et … son défunt mari », 7 February 1777

46. See the title page of Félix-Jean Prot, Les Reveries Renouvellées Des Grecs Parodie d’Iphigénie En Tauride l’arrangement Des Airs et Les Accompagnements Sont de Mr Prot Musicien de La Comédie Françoise (Paris: Houbaut, 1779), on which we read that the music engraving was by : « Mme Vendôme et Mlle sa fille, rue Saint-Honoré, chez le march. de bas au coin de la rue du Champs Fleuri ». See above for my speculation that Marie-Charlotte Vendôme ‘adopted’ Beatrix-Francoise Moria, Francois’s daughter by his second marriage, and that Béatrix-Françoise is the “Mlle Vendome” implied here. However, it may well be that Marguerite Vendôme is in fact the engraver here, together with her own daughter.

47. Albanese Second recueil de chansons avec accompagnement de violon et la basse continue… gravée par Mlle Vendôme. Gallica, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9081973t

48. Archives des Yvelines, Commune de Buc, 1MI-EC 7 (Baptêmes, Mariages, Sépultures), 26 November 1782

49. For the identification of Mathieu-Jean Brichet , Vendôme’s second husband we can thank the « Fichier Laborde », (BNF, Manuscrits, NAF 12215), 64, 921, 2 October 1787, a transcription of a baptismal register of Charles-Mathieu Verdure, noting Marie Charlotte Vendôme and her husband, « Mathieu Brichet de Saint Quentin » as Godparents. Incidentally the mother of Marie-Charlotte’s godchild was Marie-Françoise Moria, daughter of François Moria, another proof of the affective ties remaining between Marie-Charlotte and one branch of Moria’s family after his death. On Mathieu-Jean Brichet (de Saint Quentin), see Alexandre Tuetey, Répertoire Général Des Sources Manuscrites de l’histoire de Paris Pendant La Révolution Française. Tome 9…., Vol 9 (Paris, Imprimerie Nouvelle, 1890), i-ii ; P. Caron, (ed.) Paris Pendant La Terreur : Rapports Des Agents Secrets Du Ministre de l’Intérieur. (Paris : Picard, 1910), Vol. 6. 1er-11 Germinal an II (21-31 Mars 1794), esp. IV, pp.7, 19, 37, 77, 398.

50. It is also worth noting that Marie-Charlotte Vendôme , now a ‘Widow of the Terror’, got married for a third time to Jacques Vincent Bougeart in July 1795. See Archives de Paris, AD75 V10E12 20/07/1795 Table of marriages in Paris, France 1793 – 1802 (the parents’ names given in this register, which match those of the Moria/Vendôme marriage document, leave no room for doubt that this is our Marie-Charlotte Vendôme). Her subsequent life and the date of her death remain obscure.

51. Anik Devriès-Lesure, “Technological Aspects” in Rudolf Rasch, Music Publishing in Europe 1600-1900: Concepts and Issues Bibliography (Berlin, BWV, 2005) 82.

52. Devriès-Lesure, “Technological Aspects”, 82-3.