Look:

View Image(s): Chantilly, 1773, Compare

Image Metadata:

Image Description:

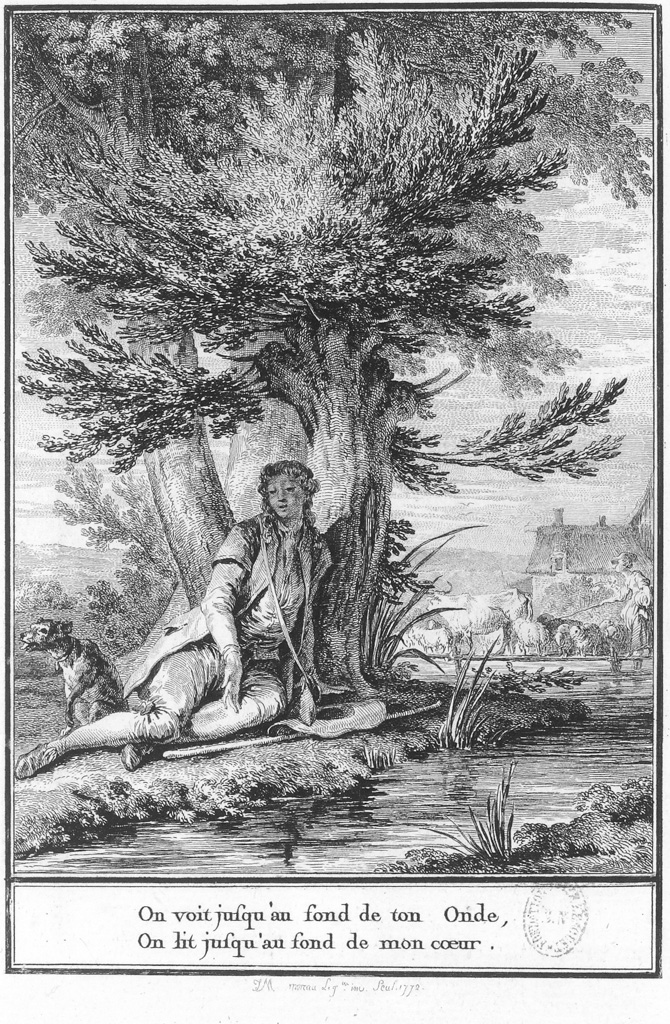

The bergere or shepherd boy that appears resting on the ground in the shade of an elm tree is dressed more for an appearance in a courtly pastoral play than for a day of work in the field. He wears a simple justaucorps, waistcoat, and culottes, the simple bag on that hangs from a strap about his neck, the broad-brimmed hat and shepherd’s staff on the ground are the theatrical attributes that identify him as a figure from the pastoral repertoire. Likewise, the bergette ‘Thémire’, in the background of the picture—the object of the shepherd’s desire—wears the loose-fitting skirts and petticoats and a broad bonnet familiar from the endless pastorals of François Boucher, and Jean-Honoré Fragonard that were so popular in the 1760s and 70s.

The Shepherd gestures down to the brook in front of him, the legend written below “On voit jusqu’au fond de ton Onde/On lit jusqu’au fond de mon coeur” [One sees to the bottom of your waters/One reads to the bottom of my heart.] These words in the chanson come after the young shepherd muses on how the water of the brook seems to reflect as in a portrait, the image of his love, the shepherdess Thémire. The shepherd makes the same equivalence between himself and the brook in the first stanza of the chanson: “Ruisseau qui baigne cette plaine/je te ressemble en bien des traits” [Brook that bathes this plain/I resemble you in many ways]. The equivalence of the shepherd and shepherdess with their idealised, arcadian environment recalls Enlightenment values espoused by the philosophe Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who called for a return to nature—to be more in tune with the natural order, rather than what he saw as the false, artificial, and mannered behaviour of the ruling class at Court.

Moreau himself was familiar with Rousseau’s work, having been engaged to illustrate an edition of his complete works at around this time. Some scholars have been eager to find an enlightenment sensibility in the work of this printmaker, but the pastoral as a genre was not always well received by the philosophes. One might recall the words of Diderot in his salon critique of 1765 “Will I ever be done with these cursed Pastorals!” For Diderot, the artifice of those pastoral scenes was a distraction from the didactic moral potential of the work of art.

Plate Signature: “JM moreau Le Jne. inv. Scul. 1772.”

Artist: “Moreau, Jean Michel”

Engraver: “Moreau, Jean Michel”

Year: 1772

Inscription: “On voit jusqu’au fond de ton Onde, / On lit jusqu’au fond de mon cœur.”

Keywords: benches (furniture), bridges (built works), cattle, cattle driving, cottages, cows (mammals), day (time of day), dogs (species), exterior, flocks, hats, pastoral, peasants, sheep (genus), shepherdesses, shepherd’s staffs, shoulder bags, staffs (walking sticks), streams, trees

Texts which refer to this image: Mahérault, L’oeuvre de Moreau le jeune, 26

Other works of art quoted in this image:

General Metadata:

Group Page Range: Vol. 1, 42-46

Title Page Inscription: “LE / RUISSEAU”

Published Notes:

Listen:

View Score(s): 1773

Song 1 recording: Ruisseau qui baignes cette plaine

Song 2 recording: Mon dieu qu’on a de peine

Credit: Paul McMahon, tenor

Amy Moore, soprano

Erin Helyard, harpsichord (French double by Carey Beebe after Blanchet, 1991)

Temperament: Jean-Henri Lambert, 1774, A:392

Song 1 diction recording:

Song 2 diction recording:

Credit: Eighteenth-century diction prepared and declaimed by Linda Barcan with the assistance of Erin Helyard and Veronique Duche

Music Metadata:

Song 1 Description:

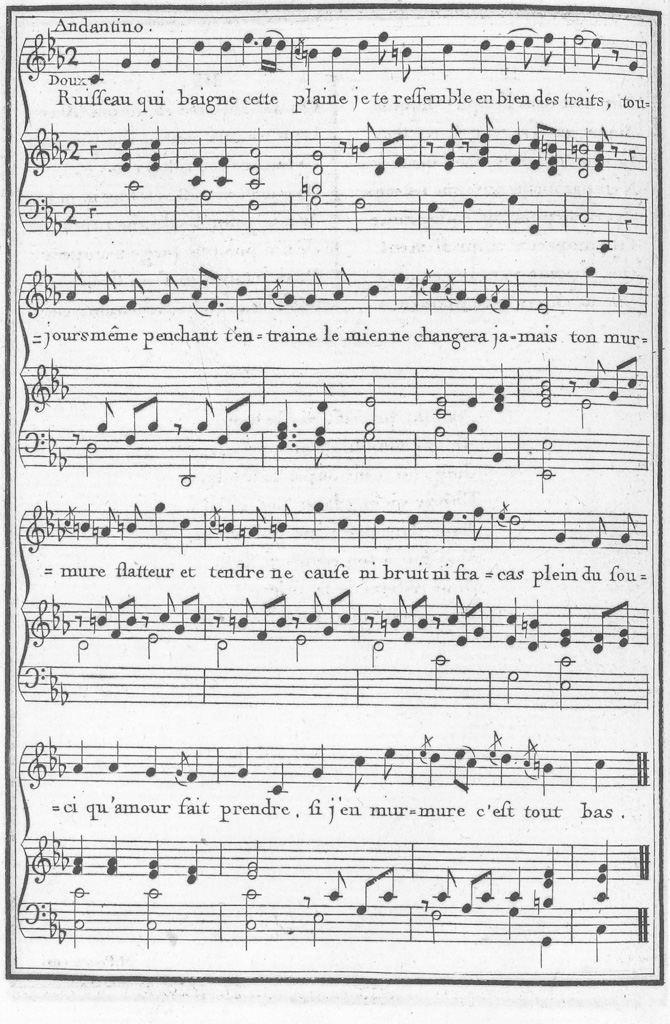

This exquisitely rendered chanson is a sommeil or “slumber scene,” an operatic convention that has its roots in Venetian opera of the mid-seventeenth century. Such a scene was popular in that it often hushed a noisy audience with extreme effects of dark lightning and soft instruments. The slumber scene for both the French and the Italians served to place a character in a vulnerable position in which a variety of dramatic scenes could take place: either exploring the themes of potential violence (rape), love, eroticism, and often the sleeping character spoke in their sleep, thus revealing important information to advance the plot. Slumber scenes thus either increased or decreased dramatic tension, or did both at once, so were important as pivoting devices for both composers and librettists. Created and popularised by Venetian opera composers, Lully introduced the sommeil to France in Les amants magnifiques in 1670. It was a popular effect in the theatre and chamber (many cantatas feature sommeils) all the way into the late eighteenth century. Laborde’s chanson shares some elements of the theatrical sommeil, in particular a slow-moving melody that gravitates around a low register with an accompaniment characterised by a slow, yawning, and hypnotic harmonic rhythm. The accompaniment in this chanson, with its nervous and fast arpeggiating figure, seems best suited to the harp (which can play this figure relatively softly). This contrasting accompaniment, which stands in stark contrast to the immobility of the vocal line, might suggest the quickened breath, beating heart, or erotic arousal of the protagonist who observes the sleeper.

S.1.07.1.mid

S.1.07.2.mid

Song 1 Composer: [Laborde, Jean-Benjamin de]

Song 1 Key Signature: c

Song 1 Time Signature: 2

Song 1 Expression Marks: Andantino

Song 1 Tessitura of Voice: c1-g2

Song 1 Tessitura of Instrument: C-d2

Song 1 Strophic: Strophic

Song 1 Related Compositions:

Song 2 Description:

Song 2 Composer: [Laborde, Jean-Benjamin de]

Song 2 Key Signature: Eb

Song 2 Time Signature: 2

Song 2 Expression Marks: Larghetto

Song 2 Tessitura of Voice: bb-a2

Song 2 Tessitura of Instrument: Eb-f2

Song 2 Strophic: Strophic

Song 2 Related Compositions:

Read:

Song 1 Transcription:

I

Ruisseau qui baigne cette plaine

je te ressemble en bien des traits,

toujours même penchant t’entraine

le mien ne changera jamais

ton murmure flatteur et tendre

ne cause ni bruit ni fracas

plein du souci qu’amour fait prendre,

si j’en murmure c’est tout bas.

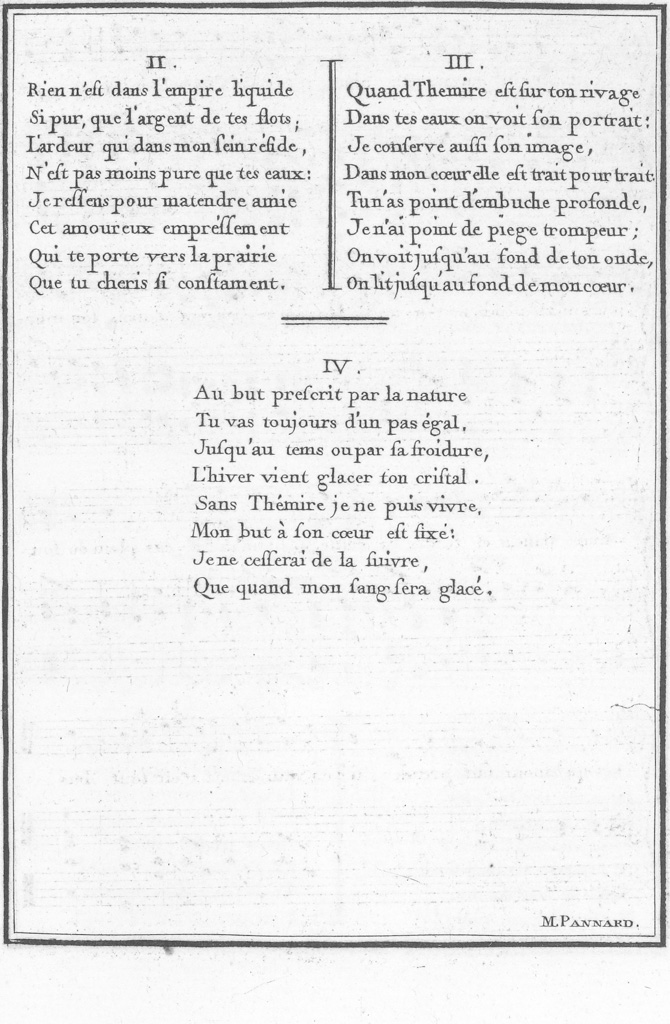

II

Rien n’est dans l’empire liquide

Si pur, que l’argent de tes flots;

L’ardeur qui dans mon sein réside,

N’est pas moins pure que tes eaux:

Je ressens pour ma tendre amie

Cet amoureux empréssement

Qui te porte vers la prairie

Que tu cheris si constament.

III

Quand Themire est sur ton rivage

Dans tes eaux on voit son portrait:

Je conserve aussi son image,

Dans mon cœur elle est trait pour trait:

Tu n’as point d’embuche profonde,

Je n’ai point de piege trompeur;

On voit jusqu’au fond de ton onde,

On lit jusqu’au fond de mon cœur.

IV

Au but prescrit par la nature

Tu vas toujours d’un pas égal.

Jusqu’au tems ou par sa froidure,

L’hiver vient glacer ton cristal.

Sans Thémire je ne puis vivre,

Mon but à son cœur est fixé:

Je ne cesserai de la suivre,

Que quand mon sang sera glacé

Song 2 Transcription:

I

Mon dieu qu’on a de peine

à conserver son cœur,

une amoureuse chaine

promet tant de douceur,

Eh! pour quoi se deffendre

de suivre son desir?

Souvent à trop attendre

on perd bien du plaisir.

II

Corine sur mon áme

Doit regner à jamais;

Déja ma tendre fláme

Egale ses attraits.

Mon amour, à L’aurore

M’annonce un jour serein;

Puisse le Soir encore

Ressembler au matin!

III

Nuit et jour je soupire,

Je voudrois exprimer

Ce que mon cœur desire,

Mais je ne sais qu’aimer.

Helas! puisse Corine

Le deviner un jour!

Tenés, quand on devine,

C’est permettre l’amour.

Text Metadata:

Song 1 Text Description:

Song 1 Incipit: Ruisseau qui baignes cette plaine

Song 1 Author: “Panard, Charles-François”

Song 1 Text Keywords:

Sources that refer to song 1 text: Restout et al., Galerie Francoise 2,

Sources that song 1 text refers to:

Song 2 Text Description:

Song 2 Incipit: Mon dieu qu’on a de peine

Song 2 Author: Ménilglaise

Song 2 Keywords:

Sources that refer to song 2 text: Laborde, Essai sur la musique 4, 244-245