The Choix de chansons of 1773 is a fascinatingly multi-faceted work allowing multiple points of access. For each song or set of two songs, a full-page engraved illustration depicting a scene associated with the song is followed by a title page, and then the song complete with the full engraved score on three pages. Where, as is often the case, the engraved song fits on a single page or two pages, a second song is added to the set under the single title and illustration to make up the three pages of score. The name of the poet, the author of the verse, is given at the end of the music, within the score. Here, for example, you see Marmontel indicated as author of the second text for the song-set titled Le Déclin du Jour. When looking at the text of this song, however, it becomes soon clear that the text has very little to do with this title:

Comment Colin Sait il donc que je l’aime?

j’ai si bien l’air de le haïr!

Est ce mon cœur qui s’est trahi lui même?

Est ce l’amour qui m’a voulu trahir?

While it is common that within the segment of light poetry and chansons titles are subject to change or might be missing altogether,[1] here it seems that titles are given to the first song in a set and the second song (if there is one) is inserted without paying attention to any possible links to the title or subject matter of the first one. The pragmatic and technical aspects of printing, calling for three pages of text and/or sheet music are the main focus and thematic links are not sought, even where they might have been easily established. For example the title ‘Les plaisirs du printemps’ could have easily accommodated, together with the song by Laborde that fills the first two pages, a poem by François-Jean de Chastellux on a house martin (‘Aimable hirondelle’) building its nest in spring (‘Le Printens t’appelle, / la saison nouvelle / t’offre mille appas’) that appears a few pages later in a set entitled ‘L’heureuse nuit’ to which it has no connection on a thematic or semantic level. Clearly, it was not Laborde’s ambition to create a coherent ensemble within each of the sets and isotopies within the poems are not used to group them together; the collection, in addition to the pragmatic considerations of layout, seemingly seeks to highlight variety in tone and topic rather than wanting to create obvious links.

Variety is one of the key aspects that any poetic anthology strives for, and one way of considering and reading this collection of 100 songs is to treat is as a poetic anthology.

The verses of the 100 songs, spread across four volumes, are written by a total of 28 poets: this is, in effect, Jean-Benjamin de Laborde’s verse anthology, and the choice and range of texts is extraordinary, ranging from the first half of the sixteenth century (Marot) to the second half of the eighteenth, and including the most famous living poet of the age, Voltaire. It is widely thought that French poetry reaches a nadir in the eighteenth century,[2] but Stéphanie Loubère has argued against this view, pointing to the dynamism of light verse in this period.[3] Light verse can embrace many forms, including occasional poetry and poésie fugitive, and it certainly includes verses that are set to music: Laborde’s anthology of verse needs therefore to be situated and understood in the context of the taste and debates of his time.

Determining the precise number of poets present in the anthology is a more difficult task than would appear at first sight. A significant number of the songs, twenty-one, are signed with two asterisks: the meaning of this signature is not entirely clear, but it may simply designate unattributed or anonymous verse. What is clear, however, is that one author dominates the collection, and that is the composer himself: Laborde, using his signature of three asterisks, is responsible for a total of thirty-one poems, and he co-signs a further six; overall, therefore, he puts his name to over a third of the songs in the collection. Interestingly, he signs over a half of the songs in volumes 1 and 2, and the number dwindles thereafter: it would appear that Laborde began using his own texts wherever possible, and that as his own supply of suitable verse began to run dry, he resorted increasingly to finding other appropriate poets.

The two poets most frequently chosen by Laborde, after himself, are names now utterly obscure. The Chevalier de Menilglaise signs seventeen songs, while Le Prieur signs eleven. Both men are military officers, as we learn from Laborde’s later descriptions in his Essai sur la musique:

Le Chevalier de Menilglaise, officier au regiment des Gardes Françaises, d’une ancienne maison de Normandie, et neveu de M. l’abbé de Canay, si aimé et si considéré de tous les gens de lettres, a donné à la poésie quelques moments de ses loisirs. Nous connaissons de lui plusieurs pieces charmantes jouées en société, et une infinite de chansons agréables. [link]

M. Le Prieur, Officier de la Chambre du Roi, a fait des pieces charmantes en vers et en prose. Il est bien fâcheux pour les arts que des occupations plus sérieuses et plus utiles lui aient fait abandonner une carrière, qui lui promettait les plus grands succès. [link]

We are then left with a large number of poets who sign just one or a very small number of texts, and this interesting group includes some surprises.

Firstly, in addition to Menilglaise and Le Prieur, there are other minor and obscure figures from the French seventeenth and eighteenth century: Pierre-Joseph Bernard, Chabanon de Maugris, Devismes de Saint-Alphonse, François de Neufchâteau, La Sablière, Marquis de Mimeure and Gigault de Plumeteau. The last of these, utterly obscure today, according to a different collection of chansons, the Anthologie française (1765), was Gentilhomme ordinaire du roi, died in 1758 and seems to have left few records of his activities. Laborde’s Essai sur la musique mentions this and also hints at a personal connection between Laborde and the author:

Personne ne connut mieux que lui les graces & la délicatesse de la poésie. Il se préparait à donner quelques ouvrages lyriques […] lorsque la mort vient l’empêcher d’y mettre derniere main. Il serait à desirer que sa respectable famille […] rendit homage […] en rassemblant les productions éparses de cet aimable Poëte […]; c’est le vœu de tous ceux qui, comme nous, ont eu le bonheur d’être aimé de lui […]. [link]

The Choix de Chansons as well as the Essai, both reproducing a number of poems and songs by de Plumeteau, then, serve as a kind of homage and are responsible for keeping the work of this hitherto unpublished author alive.

In this particular case, this seems to have been fairly successful, but only with regard to the work and less so the name attached to it. For one of the songs by de Plumeteau has made it into the Pleiade – but under the name of no other than Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The latter had included the lines and an air composed by himself in Les Consolations des misères de ma vie, published posthumously in 1781. Rousseau, in most cases, mentions where he got the lines for his chansons, but not so in this instance and hence the text entered into the Œuvres completes as his creation. It seems not unlikely, that Rousseau got the text from Laborde’s collection; two airs on a poem by Laborde precede in his collection, but whereas Laborde’s name is given, Rousseau does neglect to mention de Plumeteau.

Rousseau himself is also present in Laborde’s anthology. In fact, he is closely associated there with de Plumeteau because the second poem in the set containing de Plumeteau’s poem is attributed to Rousseau (‘Les jours que l’on passe à vous voir’). Is it possible that Rousseau’s attention was drawn to the poem by de Plumeteau precisely because the two poems appear closely together? In any case, the songs and their attributions clearly show how difficult it is to keep track, even today, of these short and highly mobile productions with their instable attributions, changing airs and titles.

While on the subject of titles, it might be worthwhile noting that the last title in Laborde’s anthology might be another tip of the hat to Rousseau: ‘Le Devin du Village’ was the title of a one-act opera (intermède) by Rousseau, one that Laborde, in his Essai considered proof that Rousseau was ‘ni Poëte ni Compositeur’. The fact that Laborde crowns his anthology with a song by himself, giving it a title highly reminiscent of Rousseau’s opera might be seen as final act of self-promotion, asserting himself as the one who should be considered author of ‘Le Devin du Village’.

Laborde’s collection, thus, seems to be highly personal, a means to publish his own works and those of his friends among those of more well-known names: Dorat and Saint-Lambert, for example, are both prominent names from the eighteenth century, and Clément Marot is a major figure from the sixteenth. Dorat is remembered as the most prolific author of light verse in the century, and he was also known as a theorist of light verse. Marot, on the other hand, can often be seen included in collections of light verse in the 18th century; his name, often mentioned in the title (‘Depuis Marot jusqu’à …’), serves almost as a generic marker signalling light poetry. Two other poets included are minor names that are still remembered, Colardeau and Panard.

Surprisingly, we also find names of well-known writers who are not primarily remembered as poets: Vivant Denon, Houdar de La Motte and Paradis de Moncrif. There is also a cluster of aristocrats, not particularly known as writers at all, but most likely friends of Laborde, and seemingly included for reasons of sociability, or perhaps sales: the Marquis de Saint-Marc, Claude comte de Bissy and Jean-Philippe d’Orléans, the illegitimate son of the Regent, known as le chevalier d’Orléans.

Another intriguing group contains the prominent names of philosophes, not necessarily known as light poets, but certainly prominent names in the literary world of the French Enlightenment: Fontenelle, François-Jean de Chastellux, Marmontel, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and (with one poem only) Voltaire. It would be rash to conclude, however, that there is any sort of bias in Laborde’s selection towards the philosophes, since he also includes the lawyer Antoine-Louis Séguier, who was elected to the Académie française without being a writer and who was a vocal opponent of the philosophes.

Finally, in this long line-up of men, there are two women: this small number of women poets is perhaps surprising when we consider that the Choix de chansons surely aimed in the first instance to please female readers and performers. The two women authors in question are not obvious choices either, given that they both flourished in the early part of the century: Catherine Bernard (who died in 1712) was a poet, novelist and playwright, while the comtesse de Murat (who died in 1716), who signs one song, was a reputed author of poetry and in particular of fairy tales.[4]

Overall, this amounts to an eclectic choice. While most of the poets are from the eighteenth century, some are earlier (notably Marot), and with such names as Mme de Murat, Fontenelle and Houdar de La Motte, there is a definite cluster of writers from the turn of the previous century, the era of the Querelle des Anciens et des Modernes, when the status of poetry was a major topic of debate. Laborde’s choice of poets is idiosyncratic, gently old-fashioned, pertaining to his own circle while clearly trying to establish a link to well-known figures and a literary tradition of songs and light verse that has its own tradition. Then there are a few big names, such as Marmontel, surely designed to give profile to the collection; he has just one song, as does Voltaire, who appears in the final volume, as if Laborde was keeping the biggest name for the end.

Laborde’s anthology, then, is both an idiosyncratic collection, but at the same time a typical example of the practices of collection in 18th-century recueils and anthologies. There is a strong element of promoting his own poetry and that of his circle and acquaintances, which in turn is mixed with some texts by the most well-known figures of the time and earlier examples that serve as a mark of a poetic (and musical) tradition into which the anthology tries to inscribe itself.

The presence in this collection of Voltaire, as the most celebrated writer of the century, is clearly a mark of prestige. When Laborde visited Ferney in September 1766, Voltaire claimed to be ‘étonné de son talent’,[5] and the two men remained in correspondence: there survive eleven letters exchanged between them in the years 1765 to 1774. A copy of the first edition of the Choix de chansons is to be found in Voltaire’s library, a copy that may well have been sent to him by Laborde.[6]

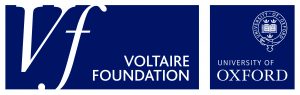

Figure 1. Louis Joseph Masquelier after Vivant Denon, 1774, Frontispiece for Choix de Chansons.

Voltaire is present from the start: Laborde’s portrait, drawn by Vivant Denon, appears as the frontispiece of the first volume, and beneath it is a quatrain by Voltaire that he had previously sent to a mutual acquaintance in 1768:

Avec tous les talents le destin l’a fait naître;

Il fait tous les plaisirs de la société,

Il est né pour la liberté

Mais il aime bien mieux son maître.[7]

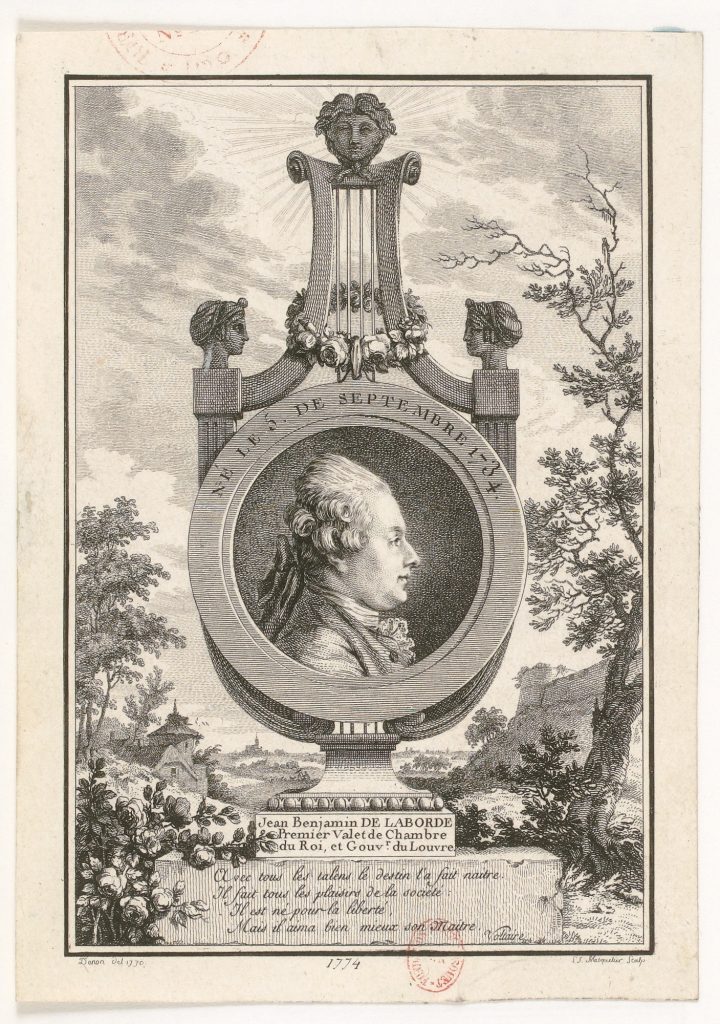

The setting of Voltaire’s own poem is in volume 4, and the engraving that precedes the song contains a figure with an uncanny resemblance to Voltaire. These are the verses usually known as the Stances à Mme Du Châtelet, ‘Si vous voulez que j’aime encore / Rendez-moi l’âge des amours.’[8] The poem treats touchingly the tension between love and friendship, and, despite its familiar title, it was actually written, it seems, for his friend Cideville. This is one of Voltaire’s most celebrated pieces of minor verse, and it was rendered into Russian by Pushkin. There are translations into English by William Fleming (1901), Ezra Pound (1916), and an outstanding version by the modern American poet Richard Wilbur.[9] The title here is interesting: ‘Le Dernier parti à prendre’. Voltaire is not known to have used it elsewhere, as we must assume that it has been invented by Laborde himself.

Figure 2. Louis Josephe Masquelier, after Jean-Jacques François Lebarbier, Le dernier parti à prendre, Choix de chansons S.4.20

Titles are flexible in this anthology as we have seen, but so are, in fact, the texts themselves. Witness, for example, one song by Laborde:

Je sens le plus affreux dégout

éloigné d’Isabelle,

elle me consoloit de tout,

et rien ne me console d’elle,

et rien ne me console d’elle.

[…]

This, clearly, is Laborde’s own text, but the inspiration as well as the central two lines of his poem go back to a much older poem by La Sablière published on multiple occasions since the 1680s:

Que mon destin est rigoureux!

Iris, l’aimable Iris a perdu la lumiere;

[…]

Iris me consolait de tout,

Et rien ne me console d’elle.[10]

This leads us to a further question: to what extent were the first readers of the Choix de chansons already familiar with the texts set to music? In the case of the Voltaire lyric, it was already widely known before Laborde chose it. But this is not always the case with verses set in the Choix de chansons: some of the poems chosen by Laborde were already known and published, while others were published here for the first time. Still others, like the one just mentioned, take parts of older texts and incorporate them into new songs, raising the question whether the reused parts were meant to be identified as such, whether the audience was supposed to savour them as skilful reappropriation or whether the recycling went unnoticed. To better understand the circulation of the texts used in this collection, we really need to use digital tools to analyse the transmission and re-use of the texts.

As we have seen, authorship is a far from settled category in the Choix de chansons, with even the composition of the songs remaining open to much debate. Initially, as most of the songs had no specified composer, we assumed that they must have been written by Laborde himself. However, as our collaborator Erin Helyard has shown in his article “Music and Music-making in Laborde’s Chansons pittoresques”, Laborde had, in fact, compiled a selection of both new and old chansons, the latter being folk songs drawn from earlier published collections. It is much the same situation with the authorship of verse in the Choix de chansons: some eighty songs have no inscribed author, but, rather, a series of two, three or four asterisks where the author’s name would normally occur. A note inscribed at the end of each volume’s index explains that “les paroles des chansons marquées par *** sont de L’Auteur de la Musique.” For much of the project, before we realised that Laborde had not composed many of the songs himself, we assumed that this meant that Laborde was the author of these poems. Now, like the scores, we are in a position to attribute some of these to previously unknown authors.

Authorship attribution is a famously tricky editorial task, but it is one to which digital methods should be able to provide insight that human readers and editors might well miss. Using sequence alignment algorithms, for example, developed initially to find regions of similar DNA sequences in the human genome, can help us identify textual reuses (citations, borrowings, allusions, plagiarism, etc.) that occur in large-scale textual databases.[11] By identifying either previous or later reuses of the Choix de chansons poems, we aimed to situate the book in the larger intertextual networks of French Enlightenment print culture, much like our colleagues work on the iconography and musical scores during the same period.

To do this, we used the Text-PAIR sequence alignment system to compare the TEI-XML digital edition of the Choix de chansons to a massive database of early-modern French texts, assembled by the ERC project ModERN at Sorbonne University.[12] The ModERN database is comprised of over 13,000 books or book-length texts across a variety of disciplines from Jurisprudence to Religious History, with a strong representation of literary texts including drama, poetry and prose from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. It is perhaps surprising then (or perhaps not) that our initial alignment of the Choix de chansons yielded only 40 or so shared passages with this enormous collection, and only a handful before its publication date of 1772. This could mean one of two things: either Laborde drew on very few ‘canonical’ works to compile his songbook, or, more likely, the ephemeral nature of poetry (and, by extension, songs) in the eighteenth century meant that a database of printed material, no matter how big, may be ill suited for identifying these sorts of cultural objects, which were diffused using different informational networks.

Nonetheless, we do find an alignment with Clement Marot’s epigram LIII from 1526, which appears as the second song of S.4.04 L’heureux maladroit. Coincidentally, Marot’s poem was also used by Voltaire at roughly the same time the Choix de chansons were published, in the article ‘Epigramme’ of his Questions sur l’Encyclopédie published in 1772:

Marot en a fait quelques-unes où l’on retrouve toute l’aménité de la Grèce.

Plus ne suis ce que j’ai été

Et ne le saurai jamais être,

Mon beau printemps et mon été

Ont fait le saut par la fenêtre.

Amour, tu as été mon maître,

Je t’ai servi sur tous les dieux.

Oh! si je pouvais deux fois naître,

Comme je te servirais mieux!

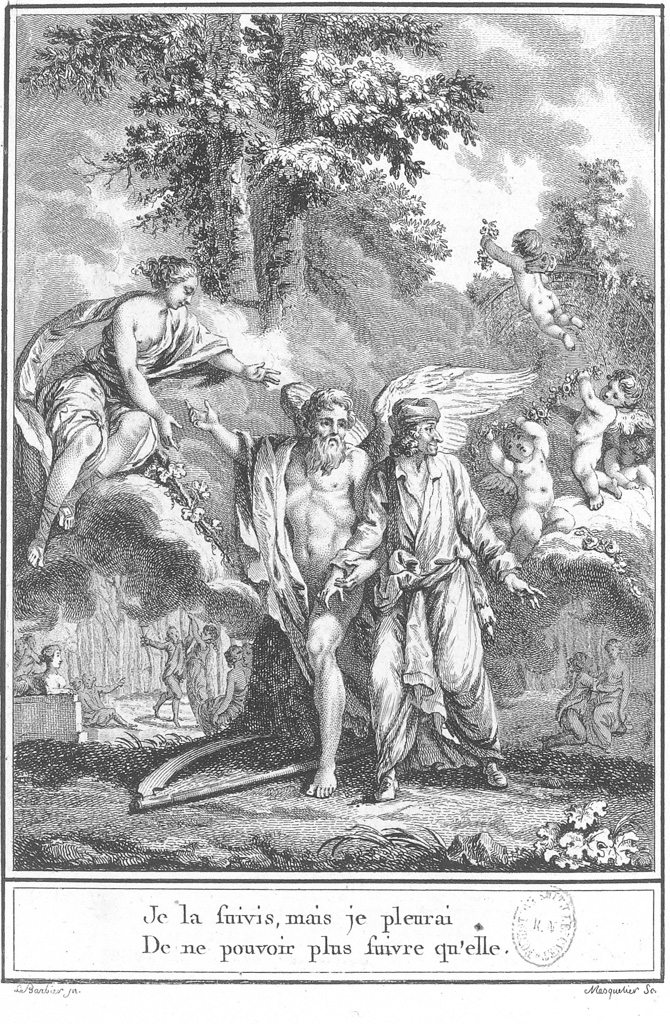

We then find the alignment of the aforementioned S.4.20 Le dernier parti a prendre and Voltaire’s Stances à Mme Du Châtelet, before finding a previously unknown alignment between the Abbé de Lattaignant’s collected poetry, published in 1757,[13] and the second song of S.3.08 Les plaintes mutuelles. As we can see in Figure 3 (bottom right), the song is attributed using two stars, which is neither a direct attribution, as we find with other songs, nor the above-mentioned three stars that were meant to represent Laborde’s own contribution. Why Lattaignant was not indicated as author of these verses we cannot know, but perhaps the two stars were meant to function as a placeholder for authors that for some reason Laborde chose not to disclose. What we do know is that this was far from a simple copy-and-paste: of the eight six-line strophes in Lattaignant’s ‘Ode philosophique’, strophes three, four, five and seven are used for the song, refashioning them to fit Laborde’s needs, and further complicating accepted categories of authorship.

Figure 3. Song 2 from S.3.08 Les plaintes mutuelles.

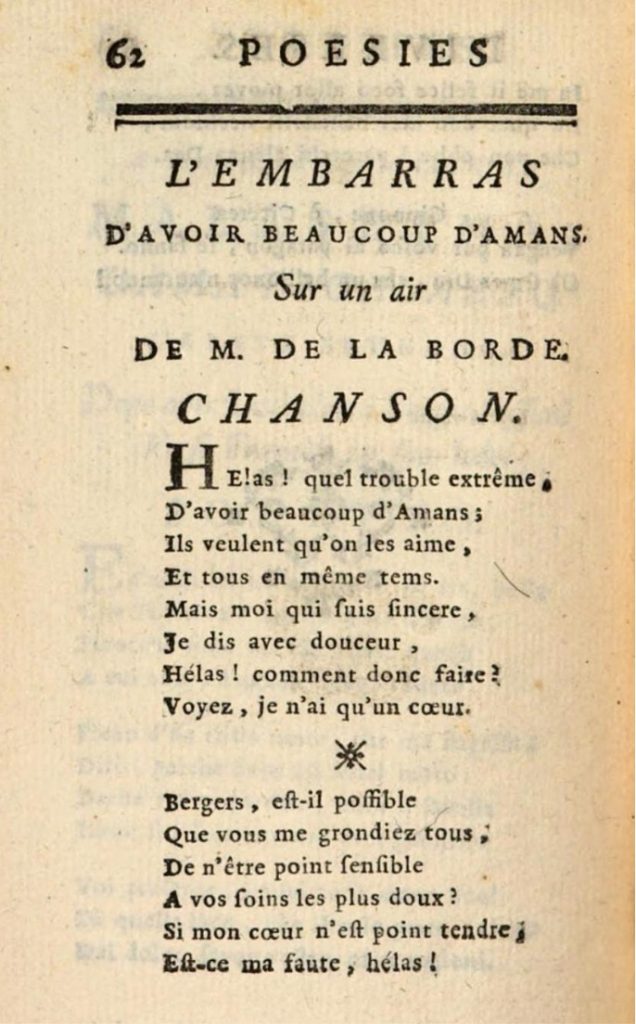

Next, we found two songs from François-Augustin de Paradis de Moncrif’s Poësies diverses,[14] published in 1761: the second song of S.1.01 Le portrait reconnu and the first song of S.1.15 L’ingénuë, both of which are attributed to Moncrif and include the entirety of each poem. The latter example, it seems, was already set to music by Laborde for Moncrif (see Figure 4), with only a slight change in wording—exchanging ‘Mon Dieu’ for ‘Hélas’—between Moncrif’s version and Laborde’s reuse in the Choix des chansons.

Figure 4. Song one of S.1.15 L’ingénuë in Moncrif’s Poësies diverses, 1761.

There are thus mostly later reuses identified in the ModERN corpus of Laborde’s chansons, for the most part found in another songbook, the Chansons choisies, avec les airs notés, published in 1783-1785.[15] In all some fifteen songs are shared between the two works, including: song one of S.1.07 Le ruisseau by Panard; song two of S.1.08 La toilette by Séguier; song two of S.1.15 L’ingénuë purportedly by Laborde; song one of S.1.25 Les quatre coins by Laborde; song one of S.2.11 La statue de l’amitie by Le Prieur; a modified version of S.3.01 Anaximandre by François de Neufchâteau; song two of S.3.03 Le reproche mal fondé by Laborde; song two of S.3.04 Le retour desiré by Madame de Murat; song two of S.3.08 Les plaintes mutuelles, which as established above, comes from the Abbé de Lattaignant (via Laborde?); song one of S.3.09 L’avare et la jeune esclave by Le Prieur; S.3.17 Les souvenirs by François de Neufchâteau; song one of S.4.01 La chapelle de Vénus by Le Prieur; the third strophe of the second song of S.4.05 Le désespoir amoureux by Catherine Bernard; the second song of S.4.09 Le mort vivant by Laborde; the first song of S.4.16 La capricieuse by Saint-Lambert; and song one of S.4.23 Le lever de l’aurore by Le Prieur. Obviously, it is difficult to establish any direct affiliation with these songs, but their continued reuse in the 1780s, coupled with the fact that most of them are drawn from known authors (including two women), is a testament to the genre’s popularity and longevity.

We also find several interesting intertextual links to non-songbook texts, journals and literary manuals. In the wonderfully-titled Cataractes de l’imagination, déluge de la scribomanie, vomissement littéraire, hémorrhagie encyclopédique, monstre des monstres… published by the relatively unknown illuminist poet Jean-Marie Chassaignon in 1779,[16] for instance, we find a poem by Charles-François Panard, which forms the basis of song one of S.2.18 Le juge intégre. In that same year, we find song one of S.2.13 Le loup garou by Le Prieur reprinted as a romance entitled ‘La Veillée’ in the Correspondance secrète, politique, civile et littéraire.[17] And, in Jean Baudrais’ eclectic journal the Étrennes de Polymnie,[18] we find a partial reprint of S.2.06 Le racomodement in 1785. Rousseau’s short poem, which is used as the second song of S.2.21 Les derniers regrets d’un amant, is also included as a use-case example in Bridel Arleville’s Le petit rhétoricien françois: ou abrégé de la rhétorique françoise, published in 1791. Near the end of the century, Jean-François de La Harpe will cite two of the Choix de chansons poems in his Lycée, ou cours de littérature ancienne et moderne published in 1799: Voltaire’s Stances à Mme Du Châtelet, along with Madame de Murat’s contribution to song two of S.3.04 Le retour desiré. And finally, in 1805, we find François de Neufchâteau’s poem Anaximandre S.3.01 Anaximandre reused as the epigraph of François Andrieux’s play Anaximandre, ou le sacrifice aux grâces.[19]

While these results are far from exhaustive, they do suggest that songs and other forms of occasional verse were widely distributed in the eighteenth century in both canonical and non-traditional formats.[20] The absence of these latter sorts of publications—anthologies, broadsides, journals, ephemera—in our digitised collections is perhaps another reason we find so few reprinted or reused songs; in order to gain a better idea of a given text’s ‘communication circuit’, to borrow a term from Robert Darnton, we need more diverse and expansive digital archives.[21] The eighteenth-century press is obviously a logical place to start this process of archival expansion, and many institutions, including the British Library and the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), have begun campaigns to digitise large swathes of their early-modern press holdings.[22] Thus, working with the BnF DataLab, we have begun experimenting with these new collections as potential vectors of large-scale text reuse in the eighteenth century.

While the BnF has digitised more than 150 individual journal titles in their pre-modern collection, generic and thematic coverage is still an issue. Small, independent literary journals—of which there were many in eighteenth-century France—are often not the focus of digitisation campaigns, in which well-known titles such as the Mercure de France are represented but others, such as the Almanach des Muses, are not.[23] To rectify this problem, we supplemented the BnF press archive with as many literary-poetic journals as we could identify, mainly from Google Books. This expanded literary corpus of just under 1900 titles was then compared with the Choix de chansons using the same alignment method outlined above.

Results were again rather sparse: only 37 identified passages, with a fair amount of ‘noise.’ Due to the nature of the digitisation process, which is largely automated using ‘optical character recognition’ (OCR) software, early-modern texts often have a higher amount of mis-recognised or unrecognised words and characters. The Text-PAIR system is fairly fault tolerant, however, and was designed with these sorts of errors in mind. To see an example of what we’re talking about, here is the first identified song from the Choix de chansons (song two of S.4.07 Le danger de se deffendre) in our press collection, from the December issue of the Mercure Galant in 1692:[24]

| AIR- NOUVEAU. p _Ar une – tendre chansonnette fUy-charmé ie- tœur de Lirttte e – sHe-¡¡’a,pnJJle refustraffoy. J( crains peu les jaloux de mon bonheur extreme . j’af quelques Rivawx qui chantent mieux que mo , -Il n’ (/J; est point qui Jçdchs Aimlr- – : de. mestnc- -‘ – Mercure Galant, décembre 1692 | S.4.07.2 Par une tendre Chansonette j’ai charmé le cœur de Lisette elle n’a pu me refuser sa foi Par une [tendre Chansonette j’ai charmé le cœur de Lisette] elle [n’a pu me refuser sa foi] Je crains peu les jaloux de mon bonheur extrême si j’ai quelques Rivaux qui Chantent mieux que moi qui [chantent mieux que moi] il n’en est pas qui sache aimer qui [sache aimer] de même |

On the left we have the song as it was digitised, and riddled with OCR errors; on the right is the text of the song from our edition, which we still nonetheless identified with the shared 5-word string ‘crains peu jaloux bonheur extreme.’ While we are no closer to identifying the author of this song—the Mercure gives us no indication—we can add this information to our edition, thus enriching its content and metadata.

For all of our efforts at diversifying our corpus, however, the vast majority of the songs we find in the press come from the Mercure de France. Two instances have already helped identify further authors in the Choix de chansons: song two of S.3.22 La deffense inutile (no author) appears first in July 1726,[25] and is attributed to a previously unknown author, ‘Lainez’, and includes a published score that would be interesting to compare to Laborde’s version; and song one of S.4.14 La bagatelle (signed with two stars, and attributed to Laborde) first appears in the December 1726 issue of the Mercure as a ‘chanson’ even though, through further research, we know it to be in fact a ‘conte’ in verse by Jean-Baptiste de Grécourt published under the same title ‘La Bagatelle.’

Other appearances in the Mercure include: the second song of S.4.05 Le désespoir amoureux (attributed to Laborde), published in October 1750; song two of S.1.16 La soirée du village (Pierre-Joseph Bernard) in July 1754; song one of S.1.07 Le ruisseau (Charles-François Panard) in November 1758 and again in March 1759; the first song of S.3.04 Le retour desiré (Laborde) in May 1761; song one of S.3.19 Regrets de Petrarque (Laborde) in November 1765; Madame de Murat’s second song of S.3.04 Le retour desiré in May 1767; Jean Philippe d’Orléans’ song two of S.4.02 La consolationin July 1767; Moncrif’s second song of S.3.10 L’heureuse in October 1767 as well as song two of S.1.01 Le portrait reconnu in December of the same year; song one of S.1.19 L’effet de la peur (Charles-Pierre Colardeau) in March 1769.

Songs that are printed in the Mercure after the publication of the Choix de chansons include: song two of S.4.08 Les douces bléssures (Séguier) in Feburary 1774; the first song of S.4.16 La capricieuse (Saint-Lambert) in November 1774; verse two of song one from S.4.03 Les vendanges de Cythere (Dorat) in February 1780; the third and fourth verses of song one from S.4.09 Le mort vivant (Marquis de Saint-Marc) in April 1781; and, finally, song two of S.2.05 Le pot au lait (Laborde) in August 1788.

Often the Mercure acts a sort of relay between and towards other literary journals, and indeed we find many songs that are printed in more than one place/time: Moncrif’s romance, which will become the second song of S.2.18 Le juge intégre, for example, was published first in the Les Amusemens du Coeur et de l’Esprit in 1748,[26] then again in the Année Littéraire in 1765,[27] before appearing partially in the Mercure of February 1769. Song two of S.4.05 Le désespoir amoureux published first in the Mecure in 1750 (see above) and then again in the L’Abeille du Parnasse in 1751[28] and L’Année littéraire in 1759. L’Abeille du Parnasse also published Moncrif’s second song of S.3.10 L’heureuse in 1751. Going futher afield, Gigault de Plumeteau’s song one from S.1.22 Le départ makes a perhaps unexpected appearance in the Censeur hebdomadaire in 1760.[29] Panard’s ‘Le Ruisseau’ (song one of S.1.07 Le ruisseau), after appearing twice in the Mercure, will also be published in the Année littéraire in 1762 and again in 1775. Likewise, Colardeau’s first song of S.1.19 L’effet de la peur, published in the Mercure in 1769, will be republished a year later in the Almanach des Muses, a publication whose vocation it was to reuse the best bits of poetry published in a given year.[30]

This final reuse—a poem/song published elsewhere before being incorporated into the Choix de chansons—offers a closing example of the often-overlooked relevancy of songs in the eighteenth-century (digital) archive. Appearing first as ‘Couplets sur l’Air de M. Albanese: Mon jeune cœur palpite’ in the March 1769 issue of the Mercure de France, there are slight, but perhaps significant differences between this version and the text in the Choix de chansons:

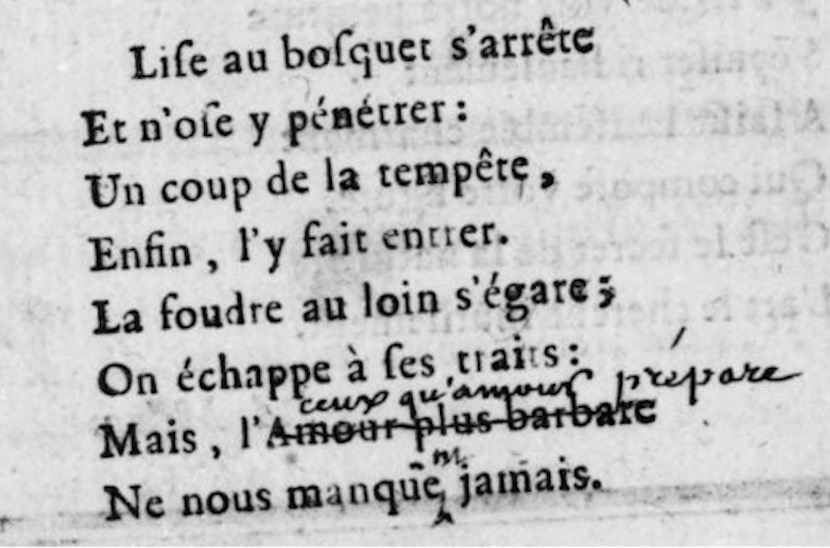

| S.1.19 L’effet de la peurI Lise entens-tu l’orage il gronde l’air gémit, l’air gémit, sauvons nous au Bocage, Lise doute et frémit, qu’un cœur faible est à plaindre dans ce double danger, C’est trop d’avoir à craindre l’orage et son Berger, C’est trop d’avoir à craindre l’orage et son Berger, l’orage et son Berger. II Mais cependant la foudre rédouble ses éclats, ses éclats. Que faire et que résoudre? faut-il donc suivre hélas? de frayeur Lise atteinte va, vient fuit tour à tour, On fait un pas par crainte, un autre par amour, On fait un pas par crainte, un autre par amour, un autre par amour. III Lise au Bosquet S’arrète et n’ose y pénetrer y pénetrer, un Coup de la Tempête enfin l’y fait entrer, la foudre au loin s’egare on évite ses traits mais ceux qu’amour prépare ne nous manquent jamais, mais ceux qu’amour prépare ne nous manquent jamais, ne nous manquent jamais. IV Ce Dieu pendant l’orage, profite des momens, des momens, caché dans le Nuage, son oeil suit les amans. Lise de son Azile sortit d’un air confus, Le ciel devint tranquile, son cœur ne l’était plus, le ciel de vint tranquile, son cœur ne l’était plus, son cœur ne l’était plus. | Mercure de France, mars 1769 Lise , entens – tu l’orage ? il gronde , l’air gémit ! ſauvons – nous au bocage : Liſe doute & frémit . Qu’un ceur foible eſt à plaindre , dans ce double danger ! c’eſt trop d’avoir à craindre l’orage & ſon berger . Mais cependant la foudre redouble ſes éclats : que faire & que réſoudre ? faut – il donc ſuivre Hilas ? De frayeur Liſe acceince , va , vient , fuit cour – à – cour ; on fait un pas par crainte , un autre par amour . Liſe au boſquet s’arrête , & n’oſe y pénécrer : un coup de la tempêce enfin l’y fait entrer . La foudre au loin s’égare : on échappe à ſes craits : mais l’Amour plus barbare , ne nous manquent jamais . ‘ Ce Dieu pendant l’orage , profite des inomens ; caché dans le nuage , son vil ſuit les amans , Lire , de ſon aſile , forcit d’un air confus ; le ciel devine tranquille : ſon cour ne l’étoit plus. |

There is an additional repetition at the final line of each verse, which was no doubt added to fit Laborde’s new arrangement, and there are noticeable OCR errors in the Mercure text on the right. But, by and large, the two songs are almost identical, save for penultimate line in the third strophe: ‘mais ceux qu’amour prépare’ in Laborde and ‘mais l’Amour plus barbare’ in the Mercure. It is hard, if not impossible, to know exactly what to make of this discrepancy: if it represents an earlier version of the text, it will be corrected by the time La Harpe and Marmontel publish the complete Oeuvres de Colardeau in 1779;[31] and if Laborde based his version on another text (which is entirely likely), no extant witness that predates the Choix de chansons is available to us in digital form. Whatever the case may be, the mnemonic power of song likely explains the presence of a handwritten annotation in the BnF’s copy of the Mercure (see Figure 3), which forcefully corrects the verse in question, before adding a quick grammatical emendation to the following verse.

Figure 5. Close up of Colardeau’s poem in the Mercure de France (BnF copy)

The source of this annotation is lost to time, and we can’t even be sure if it came from an eighteenth-century reader or, rather, an assiduous modern in the centuries to come. What we can deduce, however, even from this sparse historical record, is that transdisciplinary print objects such as the Choix de chansons represent an under-explored and under-estimated element of eighteenth-century literary and artistic production. The power of the spoken, or sung, word was likely just as operative as their written and printed counterparts, and perhaps more so. And, while literary historians tend to focus primarily on the latter to understand past cultures, we would do well not to ignore the former when they come to light. Our hope is that the above reflections are a first step to re-inserting these works into the intertextual and interdisciplinary networks of Enlightenment France while rediscovering their relevancy for eighteenth- and twenty-first-century readers alike.

[1] As for the chanson by Marmontel just quoted, it was printed, for example, in 1800 (in a collection called Esprit anacréontique des poètes Français, Paris) under the heading ‘L’Amour bien déguisé’.

[2] See, for example, Sylvain Menant, La Chute d’Icare: la crise de la poésie française (1700-1750), Paris, Droz, 1981.

[3] See La Muse légère: approaches de la poésie élégiaque et anacréontique des Lumières, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2023.

[4] See the recent edition, Madame de Murat, Contes, éd. Geneviève Patard, Champion, 2006.

[5] D13573.

[6] Bibliothèque de Voltaire (Moscow-Leningrad, 1961), no 1799. Volume 3 is missing.

[7] See D15197 and OCV, vol.67, p.387. La Harpe makes a point of quoting these verses in his review of the Choix de Chansons(Mercure de France, October 1775, p.114).

[8] OCV, vol.20a, p.560-65.

[9] See Nicholas Cronk, Voltaire: a very short introduction (Oxford University Press, 2017), p.23-27.

[10] https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k8711369x

[11] See Mark Olsen, Russell Horton and Glenn Roe, ‘Something Borrowed: Sequence Alignment and the Identification of Similar Passages in Large Text Collections’, Digital Studies / Le Champ numérique 2.1, 2011. http://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.258 and Glenn Roe, ‘Intertextuality and influence in the age of Enlightenment: sequence alignment applications for humanities research’, Digital Humanities 2012, Hamburg, 2012.

[12] On Text-PAIR, see https://github.com/ARTFL-Project/text-pair, on the ModERN project, see https://modern.huma-num.fr/.

[13] Gabriel-Charles de Lattaignant, Poésies de M. l’abbé de L’Attaignant , contenant tout ce qui a paru de cet auteur sous le titre de ‘Pièces dérobées’…, London: Duschesne, 1757. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9739796f.

[14] https://books.google.fr/books?id=YUUGAAAAQAAJ.

[15] https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9741145v.

[16] https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1133921.

[17] See https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0244-correspondance-secrete-politique and https://books.google.fr/books?id=SzsVAAAAQAAJ.

[18] See https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0421-etrennes-de-polymnie.

[19] See https://www.theatre-classique.fr/pages/pdf/ANDRIEUX_ANAXIMANDRE.pdf.

[20] See Buffard-Moret, Brigitte, ‘La chanson au xviiie siècle: un micro-genre de la poésie fugitive’, in La chanson poétique du XIXe siècle, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2006, https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.31703.

[21] See Darnton, Robert, ‘What is the history of books?’, Daedalus 111(3), 1982: 68.

[22] See https://www.gale.com/intl/essays/moira-goff-burney-newspapers-british-library and https://www.retronews.fr/periode/siecle-des-lumieres-1715-1789.

[23] On these two journals, see https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0924-mercure-de-france-1 and https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0080-almanach-des-muses respectively.

[24] On the Mercure Galant, see https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0919-le-mercure-galant.

[25] For page images of the Mercure, see https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32814317r/date&rk=42918;4.

[26] See https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0097-les-amusements-du-coeur-et-de-lesprit.

[27] See https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0118-lannee-litteraire.

[28] See https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0001-labeille-du-parnasse.

[29] See https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0203-le-censeur-hebdomadaire.

[30] See https://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/journal/0080-almanach-des-muses.