One of the most remarkable publications of the later eighteenth century is the four-volume Choix de chansons compiled by Jean-Benjamin de Laborde (1734–1794), fermier général and premier valet du chambre to Louis XV.1 Published in 1773 and dedicated to the Dauphine, Marie Antoinette, this deluxe set is a multi-authored collection of music, text, and image. Like many other recueils (or collections) of chansons from the period, it features hand-engraved musical scores for voice with accompaniment together with the printed text of strophic verses from the pens of ancient and modern poets.2 What makes Laborde’s publication so unique—he himself calls it “of a absolutely new genre”—is that each chanson also receives an elaborate engraving that either depicts a key moment of the narrative or encapsulates or symbolises the predominant theme of the poem.3 The verses set by Laborde are by a variety of French poets, whose subjects provide an extraordinarily wide panorama of eighteenth-century life. Laborde commissioned the celebrated printmaker, Jean-Michel Moreau (1741–1814), known as Moreau le Jeune, to inaugurate the project. But Moreau contributed only twenty-five plates to the four-volume set, with three other illustrators completing the collection (Le Bouteux, Le Barbier, and Saint Quentin).

Much of the existing commentary on Laborde’s publication emphasises the superior quality of the twenty-five engravings that Moreau contributed to the first volume. This positive assessment is often contrasted with Laborde’s “feeble songs and inept music” and the illustrations of the remaining three volumes by “second rate draftsmen.”4 Fétis, already unsympathetic to this period in French musical history, set the tone for Laborde’s reception history in 1837:

La Borde [sic] was very fond of his music, and naively admitted that none other gave him so much pleasure; it is, however, very mediocre, and as badly written as anything that was done in France at the time. However, he made some songs which are natural; one notices among others those which begins with these words: Vois-tu ces coteaux se noircir? [S.1.03] [and] the one which has for its refrain L’Amour me fait; belle brunette [S.3.06], and Jupiter un jour en fureur [S.2.15]. La Borde published with great luxury a Choix de chansons set to music in four volumes […] The harmony is very bad. There are many engravings there, the execution of which is as beautiful as their taste is false. Grimm took every opportunity to abuse La Borde’s music in his literary correspondence; it is indeed very insipid [plate] and very gloomy [maussade].

Because of his uneven output and his close connection to court, many have amplified Fétis’ account. Laborde stank of the aristocracy and was fattened by the blood of peasants. His music only found an outlet because of nepotism at court.6 Thus, despite Fétis’ positive account of a handful of those songs, Laborde’s musical collection has been derided and scholars of French poetry have largely overlooked his curatorship of verse. Historians of music engraving have long noted the “outstanding” quality of the four-volume set but musicologists have generally ignored Laborde’s compositions—which were scorned by prominent contemporary commentators like Grimm addition to later writers like Fétis—in favour of Laborde’s influential later treatise, the Essai sur la musique ancienne et moderne.7

In 1772 Laborde began collating songs he had compiled and written for la société du Caveau, a fraternal “Bacchic” society originally founded in 1729.8 By the 1770s, the second instantiation of le Caveau (1759–1789), as it came to be known, had become an elite network of artists and intellectuals. Members included renowned painter François Boucher, noted literary figure Jean-François Marmontel, the philosophe Helvétius, and the antiquarian the comte de Caylus. Modelled on English Masonic societies, le Caveau excluded women from meals but used music and music-making to celebrate communality between men and women.9

Thus, the courtiers in Marie Antoinette’s circle and the men and women who obtained and used Laborde’s deluxe songbooks may well have echoed those mixed-gender performances of le Caveau. Gathering themselves in intimate spaces around the music desk of a harpsichord or harp, or maybe even a new-fangled square piano, they would have sung and enacted selections of Laborde’s songs, admiring the poetry and visual imagery, lending voice and finger to each one, and together constituting a miniature operatic scene. Many of the chansons theatricalise the quotidian aspects of courtly or aristocratic life: the toilette, the secret lover, boredom, the music lesson, the ball, the opera, mealtimes, solitude, sex, reading, singing, playing, painting, sleeping, dreaming, travelling, and so on. But others feature erotic, otherworldly, or pastoral fantasy, with scenes from the Bible, antiquity, and the supernatural. A dominant theme is sensualised and idealised pastoral existence, with the familiar troupe of shepherds and shepherdesses. One could argue that Laborde’s encyclopaedic depiction of eighteenth-century life, in text, music, and image, constitutes a kind of distillation or “extended mind” of Laborde’s rarefied courtly existence.10 As such, chansons such as these might have provided its freshly immigrated dedicatee with a handsomely illustrated emotional handbook of French court culture, and exemplified by their own distinctive brand of sensibilité.

Sensibilité and the French chanson

The eighteenth century was full of active and engaged readers, connoisseurs of painting, and listeners of music, and most famously among them is Diderot, who recounts his ecstatic weeping while reading Richardson in addition to his passionate accounts of both art and music.11 As such, there is an extensive amount of existing scholarship on eighteenth-century reading, art, and music and the consequent “emotional hyperreactivity” (as Le Guin calls it) of sensibilité.12 Laborde’s Choix de chansons goes directly to the heart of the three most potent stimulants of sensibilité: music, text, and image. He makes this clear in his 1772 subscription notice to the multi-volume set, even inventing a new word for the genre itself: “chansons pittoresques.”

The taste for vocal music has spread to the point that every day we release, with success, new Recueils de Chansons [songbooks], which often differ from each other only by the title. The one we offer today is of an absolutely new genre, and we dare to flatter ourselves that it will succeed.

These “picturesque chansons” are so called because they provide an ingenious artist with various subjects for paintings, which he has designed and engraved with the greatest care. This collection will therefore have the triple advantage of amusing the mind, by means of gay & interesting verses, to flatter the ear with an easy & pleasant song; and finally to fix the eyes with tableaus rendered with all the perfection which Monsieur Moreau le Jeune is capable of.13

With Laborde’s “chansons pittoresques” we are confronted with objects that demand to be sung and played in addition to being read and gazed upon. The level of communal emotional engagement, of sensibilité, involved is thus of a very high order indeed.

Enlightenment philosophes placed music and music-making in an intriguing paradox. Music, music-making, and listening to music were considered by many to be important tools in developing sympathy, empathy, and self-reflection. This collection of delicate feelings that could be set into motion by musical activity was often called sensibilité by the French, sensibility by the English, and Empfindsamkeit by the Germans. If we are to believe the voluminous correspondence of the period, music in the chamber and the theatre inspired pleasure, joy, fear, terror, and excitement and it provoked applause, tears, sighs, and groans. It was considered a powerful influence on the hearts of men and women.. Music, by virtue of its direct appeal to the senses, was considered useful as well as problematic, and for both the same reasons. For many, this paradox was understood to be resolved primarily through music-making: the ideal Enlightened musician should “move an audience through representations of its own humanity.”14

The freedom to think for oneself then, following Kant and Rousseau, went hand-in-hand with sensibilité. The pursuit of reason was to be regulated by a careful attention to one’s own feelings just as an intellect unfettered by prejudice was to be guided by an individual’s emotions. One could move an audience through representations of itself, but one also had to instruct that same audience in virtue and nobility. Ideally music did this in the theatre, with the narratives of clemency, mercy, and justice. Here was also the strongest concentration of music (in the form of operatic performance), image (in the form of scenery and costume), and text (in the form of the published libretto). But instruction in emotional discourse was supposed to happen in the chamber too, where music played an important role in mating rituals throughout Europe in the so-called “long eighteenth century.” Here sensibilité played an important role in courtship, as men and women came together in intimate arrangements in which music enacted and stimulated a compassionate and highly attuned sociability.15 Laborde’s placement of music, image, and text in the chamber was a highly novel one.

Laborde’s 1773 collection is distinctive in that his musical genre of choice is the French chanson and not, for example, a collection of instrumental music with accompanying poems and images. (One might imagine something along the lines of the music and text in Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, but with additional images.) That the chanson was the perfect choice for communal sensibilité—and well-suited for environments as disparate as the dinners at the Masonically inflected le Caveau or the intimate boudoirs of Versailles—is made clear from its consecrated place in French musical culture as a site for “natural” sentiment. The chanson was also considered impervious to foreign trickery and virtuosity, unlike instrumental music, which often smelled of Italy.

French chansons of the late eighteenth-century had subtle variants in structure and flavour as is demonstrated, for example, by the title of a typical manuscript recueil from around 1780 that includes a chanson also included in Laborde’s 1773 collection, amongst other composers of the day as well as those from the past. This collection of songs includes “Brunêttes, Romances, Villageoises, Vaudevilles, Rondes & Autres.”16 There are no indicators in collections like these that allow the reader to determine which songs are new or old (or indeed, who the composer or poet was). Brunettes, which are often privileged first in such listings, were very popular in France throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Older, generally anonymous, brunettes were collected and published in collections from as early as 1703, in a three-volume set by publisher Christophe Ballard. Brunettes were pastoral songs whose elegant poetry and “Tendre, Aisé [&] Naturel” melodies, as Ballard describes them, reflected the ideal of unforced lyricism that so many commentators on taste refer to as touching the heart.17 Generally syllabic in setting, and with a minimum of ornaments enlivening the prosody of a sinuous and gentle melodic curve, these are distinguished by clear and elegant phrasing and structure. In essence, these older brunettes were folk songs, passed down and memorised as tunes from generation to generation, and composers like Laborde, who wrote new chansons, emulated this popular style.18

Even though modern commentators from Fétis onwards have labelled Laborde the “composer” of the 1773 Choix de chansons, a closer analysis reveals that Laborde has rather compiled a wide selection of chansons, new and old alike. All the chansons are indeed “mises en musique” [set to music] by Laborde, as the 1773 title-page says, but mixed in with Laborde’s new works are older songs that were orally transmitted (and occasionally documented as single-line melodies, as in those receuils). Laborde underlines his endeavour in the titlepage of his subscription notice: “Choix des chansons tirées des recueils de chansons” [Choice songs taken from song collections.] Laborde recycled, collated, and newly composed chansons from earlier collections for the 1774 collection, including many from his three collections of chansons with accompaniments for violin and basse continue (Paris: Moria, 1757).

De la Harpe also emphasises Laborde’s curatorship in his 1775 review of the collection, which begins:

If the greatest praise of music is to be often sung, like that of verses that are taken by heart [i.e. memorised], the success & merit of the verses presented here to the public are also assured. Who has not heard being sung a hundred times: Vois-tu ces côteaux se noircir [S.1.03], &c. Il est donc vrai Lucile [S.1.22], &c. Ah ! combien l’amour a des charmes ! [S.1.25] &c. L’amant frivole & volage [S.1.16], &c.; & so many other lines full of grace & melody? One should not expect that in a four-volume collection […] all the lyrics the musician has worked on will be equally enjoyable. Besides, since they wanted the song to always provide an image, the authors of the lyrics were all the more hampered in the choice of subjects, & can be forgiven for not always succeeding. But the merit of the composer appears all the greater when he must supplement that of the poet. There are many airs to be found here that cannot be found elsewhere.

One tune mentioned here by de la Harpe (“Il est donc vrai” S.1.22), does in fact turn up in Laborde’s Essai as an example of an ancient brunette-type chanson. There he labels the tune “Chanson Languedocienne” and it is set to different words (“Charmante Margueritte”).20 This tune was used by many composers and librettists and it turns up in the popular 1762 Annette et Lubin, an opéra comique with new and old music.21 As Charlton notes “cultivated musical enthusiasts” like Laborde “really did collect, preserve, and discuss orally transmitted melody.” He cites in this regard a 1749 letter which relates the Comte de Clermont’s efforts coaxing a shepherdess to sing with “a nice half-crown,” just so he could notate her tunes.22

Writers such as Monteclair, Ballard, and L’Affilard all regarded these kinds of songs as essential in forming the requirements for good taste in both singer and instrumentalist.23 Monteclair writes in 1720 of both their “ancient” and “modern” forms:

These artless [naïfs], tender, and natural songs have always kept them in favour despite the attacks, so often repeated, of these so-called savants who find nothing beautiful except that which astonishes them and whose worn-out taste can only be piqued by songs which are extravagant, that is, by those which have harsh modulations, wrenching transpositions, continuous dissonance, and complex textures piled up on top of each other […] I do not deny that art ought to have its rights. We cannot consider a composer to be a real composer if he produces only little chansons. […] But the for the petits airs one must have not only a natural genius, a delicate taste, and a tender disposition […]; one also has to have a lot of soul to give them the expression which they demand, and of which very few people are capable. The French can rightly boast that they are the only people who have the true taste for these little pieces which other nations call bagatelles.24

One gets the sense of the musical paradox demanded by these chansons. On one hand they are simple and artless, and yet one also needs to cultivate a sensibilité with a wide variety of responsive emotional states (genius, taste, and a tender disposition) and “beaucoup d’Ame” to perform them well, which many cannot do.

Continuing with the other characteristic genres of the French chanson, romances are defined by writers as being songs with numerous verses that recount an ancient or timeless story of love or tragedy. By the time of Laborde’s Choix de chansons the genre had spread to opéra comique and by the end of the 1780s the sentimental romance was a modern extension of the older brunette. With its simple melody, artless expression, and strophic form it was very fashionable, and particular at the court of Marie Antoinette, who apparently composed her own romance: “Ah s’il est dans mon village.”25 Villageoises are songs of a rustic nature, either in text or musical style, and often reference the characteristic sound of the hurdy-gurdy or musette. Vaudevilles were satirical songs and Rousseau comments that they “dart their rays indifferently on vice and virtue, by rendering them all equally ridiculous.” This nature, he says, prohibits them from “the lips of people of quality.”26 Rondes (often called rondes de table) were drinking songs, and are again distinguished by many refrains.27

All these differing kinds of chansons are on display in Laborde’s collection for Marie Antoinette. Many of the songs appear to have an ancient pedigree and de la Harpe notes that “there are many airs to be found here that cannot be found elsewhere,” meaning, one supposes, that Laborde was documenting them for the first time. There are songs that emulate (or document) the familiar brunettes of old, as well as the familiar villageoises, vaudevilles, and romances (only the bawdy drinking songs are missing). Laborde does not explicitly name these genres, however. Only the fashionable romance gets a mention. Three songs in the 1773 collection are explicitly described as such and all are based on tragic themes: “Le juge intégre” (S.2.18), “Le tombeau” (S.2.23), and “Le mort vivant” (S.4.09). Significant in Laborde’s collection is that many of the chansons are operatically inflected, with parodies from famous operas (S.4.09, song 2 and S.4.15) through-composed ariette-like songs (for example, S.1.04), and recitative (S.3.19, S2.25). These contrast with the more old-fashioned brunette-type chanson of indeterminate authorship and chronology, with their simpler symmetrical structure.

Cultural exchange is a dominant characteristic of the French chanson. New words were sung to old tunes that themselves were identified by the texts of their oldest settings. For example, one of the settings of Laborde’s that Fétis enjoyed, “Jupiter un jour un fureur” (S.2.15), turns up in other collections and pamphlets. New texts are directed to be sung “to the tune of Jupiter un jour en fureur.” It is impossible to establish if Laborde composed the tune or was rather just the first to document it from an oral tradition. One can find it in a 1777 comedy by Beaunoir and in an anonymous engraving from the 1780s.28 Similarly, texts from chanson collections were re-set by others. Rousseau took the words from the sample song (S.1.02) in Laborde’s 1772 prospectus and set it twice over, in two different settings, in his 1781 Les Consolations des misères de ma vie, our Recueil d’airs, romances, et duos. Rousseau also re-set to new music the words of other poems that appear in Laborde’s collection, like “Il est donc vrai Lucile.”29

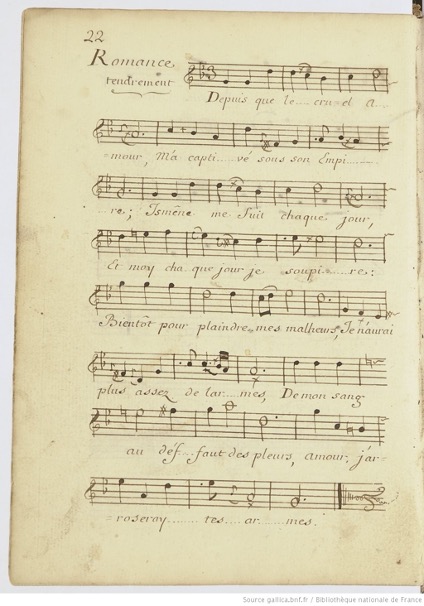

Songs and texts were thus transmitted and transplanted from one recueil to another. One can see this process, which anonymises the chanson’s author as well as its progeny (as one can’t tell if it is ancient or modern), in the romance “Depuis que le cruel amour.” Fig. 1 shows the romance in a 1780 handwritten collection. Stripped of its bass line, accompaniments, author, and time-period, one performs only the tender and sinuous melody, with its artful ornamentation that underlines the prosody. Laborde used this romance, which was first printed in his 1757 collection, again in the 1773 Choix de chansons (compare Fig. 1 with S.2.23 and note the subtle changes in ornamentation—the manuscript version prefers tremblements whereas Laborde preferred ports-de-voixs). Its presence in the manuscript collection might indicate that it was an older chanson in the oral tradition.

This erasure of historical specificity, in which the chanson inhabits a kind of timeless and idealised natural state, and in which ancient blurs with modern, accords with Laborde’s own ideas about the genre. Both Rousseau and Laborde took a characteristically Enlightenment viewpoint in their own definitions of the chanson, as they attempted to essentialise the genre with a sweeping eye to history, defining the chanson (or “song”) in European traditions from Ancient Greece to the modern day. Laborde took an even more radically global view than Rousseau by considering the song tradition in non-Western cultures.

Laborde begins his chapter on the chanson in his Essai by quoting Rousseau’s definition from his Dictionnaire:

Chanson [song]. A kind of very short lyric poem, which generally uses agreeable subjects, and to which a tune is added, to be sung on intimate occasions at table with one’s friends, with one’s mistress, or even alone; to remove, for some moments, wearisomeness, if we are rich, or to support more sweetly poverty and labour, if we are poor.

Laborde adds:

We will only add to this definition that [the chanson] is sometimes an ingenious way to write the history of one’s life and the differing situations of the soul and to declare publicly what one might not dare to admit otherwise. [The chanson] allegorically instructs the objects of our affections with what we are suffering so much in hiding from them.

Laborde and Rousseau both underline the intimate nature of the chanson, and Laborde mentions its importance in courtship, and hints at situations in which one might read between the lines and surmise hidden meaning from subject matter. Laborde also emphasises the historicising nature of the chanson, in which deeds or stories are immortalised in the many strophic verses of the chanson, just as in the heroic poems of antiquity, as he compiles and unifies in his exhaustive Essai all the songs in all the world for all of history, from China to France.

Read this way, the 1773 Choix de chansons might resemble an encyclopaedic attempt to instruct its dedicatee, Marie Antoinette, and those in her courtly circle in “all the differing situations of the soul” through the performative power of the French chanson, with its paradoxical accent on simplicity (through melody and artlessness) and complexity (through narrative and emotional range). To bring the Choix de chansons to life—to evaluate its expressive capacity through one’s sensibilité—one needed (as one needs today) to perform them. And yet one immediately discerns that there are significant obstacles to performance, as Monteclair hints at (“one also has to have a lot of soul to give them the expression which they demand, and of which very few people are capable”). Surmounting these obstacles requires some effort. Although one’s performance must appear simple and natural, as so many writers seem to suggest, several aspects of Laborde’s publication make this rather tricky, as we discuss shortly.

Music-making in the Choix de chansons

Many of the images and poems in the Choix de chansons reference the music-making activities of both men and women and indeed the entire four-volume work appears to be intended for both male and female eyes, ears, mouths, and fingers. It also highlights their origins in the equitable atmosphere of Parisian Masonic culture as imported from England.

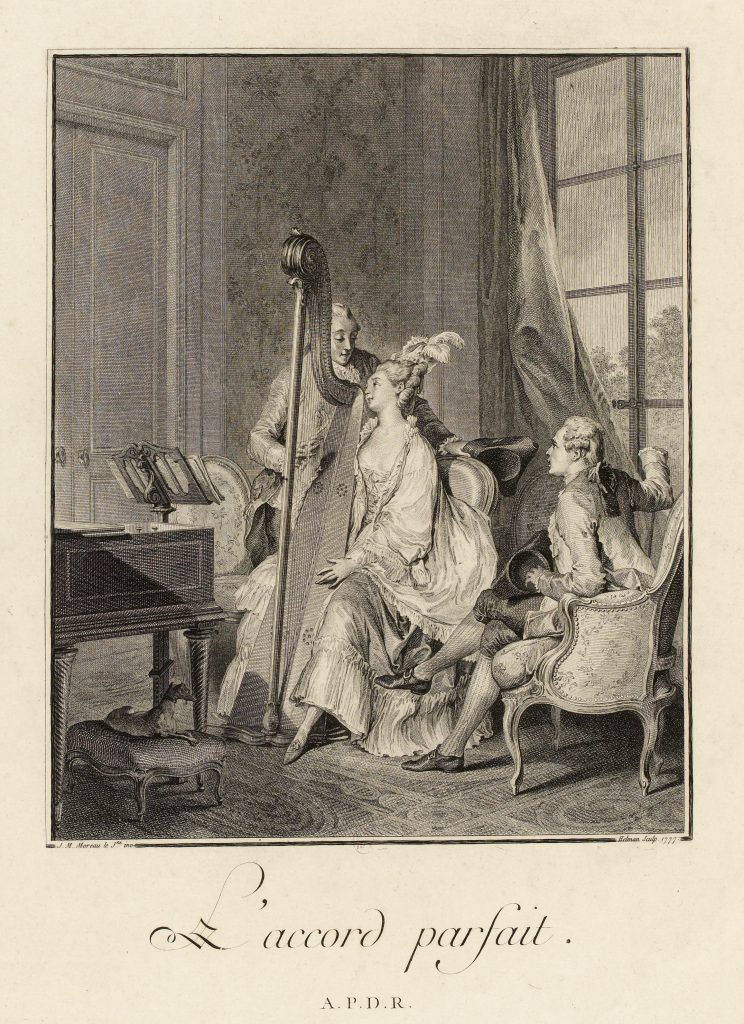

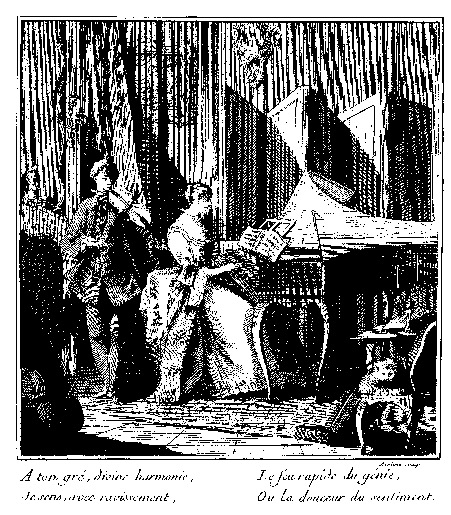

The accompaniments in Laborde’s Choix de chansons were intended for performance on the harp. This was the favoured instrument of the dedicatee once she had arrived in Paris, as can be seen in Jean-Baptiste Gautier Dagoty’s famous 1774 portrait of Marie Antoinette in morning dress. Music-making in art and literature served as a metonym for both sexual encounters as well as fortuitous courtship matches—since music was one of the few pastimes that admitted mixed contact in intimate settings, music-making became an important component of the courtship ritual and was thus inextricably sexualised in people’s minds. Moreau, one of the key engravers in Laborde’s work, emphasises this aspect in a 1777 print that features a woman at the harp in a music room with a harpsichord, with two admirers. Entitled “The Perfect Harmony,” the two hands touch as the gentleman appears to help her find the right chord (see Fig. 2). The print serves to underline the possibilities of a happy match or amorous encounter, hence the title. But it is not a strictly intimate or indeed solitary encounter, as another man watches them and, in a sense, we are also watching them too, with him. This voyeurism only heightens the erotic undertones. As Le Guin notes it is sometimes hard to determine in these situations “where sensible absorption ends and prurience begins.”32

As Laborde mentions in his prospectus, the accompaniments were designed expressly for the harp: “The editor has put a harp accompaniment to each of the songs, in favour of the people who play this instrument, which has been very fashionable for some time, & he will take great care that there is no error, neither in the lyrics, nor in the music.”33 The occasional dynamics of “doux” and “très doux” indicate subtle graduations of softness that are generally unavailable on a two-manual harpsichord (see for example, S.1.03 and S1.23). More tellingly, there are instances of a high g4 (S.2.12): this is a note that was not available on 5-octave French harpsichords of the 1770s but had been described as being in use on harps by Laborde himself in his 1780 Essai.34 Elsewhere other features include parallelism, in which parallel octaves and fifths sound more sonorously on the harp than on the harpsichord (S.2.13), right and left hand configurations with large spans (S.2.15), and idiomatic broken accompaniments called batteries, again with leaps (S.3.12, S.3.23).

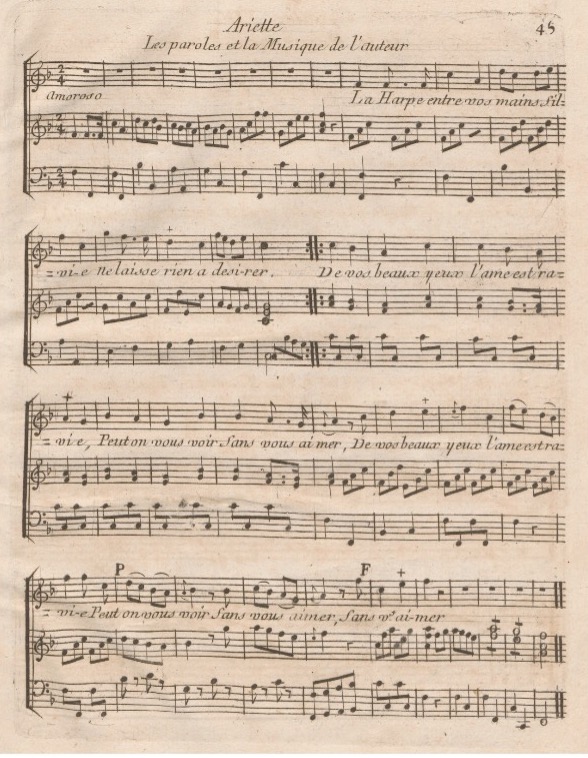

The conjunction of a thematically linked musical score, engraved image, and rhymed poem was comparatively rare in the eighteenth century, with Laborde’s illustrated collection a unique exception. However, a long-lost harp treatise by Michel Corrette from 1774 reveals this very combination in a pedagogical setting that underlines contemporary conceptions of sexualised female performance.35 These same ideological concerns are present in the imagery and poetry of Choix de chansons.

Figure 3. Frontispiece quatrain set to music on the penultimate page of Michel Corrette, Nouvelle méthode pour apprendre à jouer de la harpe (Paris, 1774)

The frontispiece of Corrette’s method features an engraving of a young woman playing a harp (see Fig. 3) accompanied by the quatrain: “The harp in your hands Silvie,/Leaves nothing to be desired./A glance at your eyes thrills me/How could you not be admired!”36 Corrette’s treatises often feature images with aphoristic quatrains. For the male clientele of the violin the quatrain promises that the treatise will unlock the secrets of harmonic power and marvellous effects (Fig 4); and for the female clientele of the harpsichord the quatrain emphasises the shifting emotions the lady will feel under the ravishing influence of divine harmony: the rapid fire of genius or the sweetness of sentiment (Fig. 5). But the harp method appears to be only one to echo Laborde’s triple engagement with text, image, and song. In a circular move of elegance, Corrette sets to music the opening quatrain of the image in the 1774 harp treatise as the final example in the volume. One opens the treatise to view the attractive image of the harpist, her musicality an allurement to male eyes; one ends the treatise by becoming “Sylvie” herself to literally enact the scenario laid out by the male authorial voice of the quatrain.

A similar connection between the male gaze and the musical accomplishments of the woman at music is found elsewhere in Laborde’s Chansons. Entitled Le Concert (S.2.22), Laborde did not set this example; rather the music is by “Milady Hamilton” or Catherine Hamilton, Sir William Hamilton’s first wife. Here the poetry explicitly refers to the appealing musical accomplishments of the lady at the harpsichord. “Your talents and your attractions/In a sensitive soul/In a short time have made too much progress;/To avoid regrets and enjoy a peaceful fate/You must always see yourself or never see yourself./Faithful image of love! Your eyes initiate our torments,/And your charming fingers complete their work.” Here are again some of the paradoxes of eighteenth-century musical life we alluded to earlier. Too much attention paid to music meant that other accomplishments had been neglected—one must play well enough, but only just. Similarly, the self-reflective female musician must always be mindful of the power of her sexualised performance. If one chooses to perform the accompaniment on the harpsichord, the image of the charming fingers is emphasised by the many crossed hands, heightening the allure of the performing musician for the audience.

The harp or harpsichord often becomes a metonym for a woman’s first lover and her sexual awakening. Indeed, after 1760, some French dictionaries even define the verb “harper” as “To play with one’s hands upon a woman, to slide one’s hands over her, to touch her private parts, to grope her with one’s fingers, rub her clitoris, and excite her with one’s fingers.”37 So strong was the connection in contemporary reader’s minds between sexuality and musicality that one poem in Laborde’s collectionexpressly links a girl’s nascent sexuality with beginner’s lessons at the harpsichord. In Le clavecin (S.2.07) Lise complains to her mother that she sings without pleasure because only her maid listens. Her mother recommends she take up the harpsichord: “you will believe it has a tender soul, and it will sigh like you.” An instrument is bought for her, Lise can’t wait to try it; but soon she discovers that when she sings a voice within repeats her phrases! Suddenly the instrument opens, and a young man falls at her feet. Night after night at the harpsichord, “our naive one/Soon learned all the tones.” One day the mother discovers them making love—in response, Lise said she was just following orders: “I thought I might as well, in following your pleasure, take a master who shows me how to understand the instrument.”

It is also significant that many contemplative and melancholic scenes in Choix de chansons feature muted instruments as background images, as if the sensual pleasure of performance with others is denied the protagonists even as the memory haunts them. A muted violin serves as a background to the unhappy lover in “Le Recuëillement” (S.3.07) and a closed harpsichord emphasises the quarrel between the capricious Climene and the confused Lindor in “La Capricieuse” (S.4.16). There is no “L’accord parfait” here.

Exercising one’s sensibilité: Performative Challenges in Laborde’s Choix de chansons

The first challenge to performance is the format of the book itself. If bound together, and with small plates (15 x 10 cm) on already small octavo pages (25 x 16.5 cm), the book is hard for the performer to effectively utilise, as singer and accompanist must peer at the tiny pages together (unless, of course, you could afford two copies). The second challenge concerns Laborde’s settings: many of the songs demand a huge range for the singer, in some cases spanning two octaves (see, for instance, S.2.22, song 2). Difficult even for a professional, these extreme ranges could stymie an amateur. The third challenge is the strophic nature of the chanson genre, and this is not exclusive to Laborde’s collection. If one wishes to sing all the strophes of a chanson, and bring the chanson’s “histoire” to life, as Laborde says himself, with a complete rendition of the narrative, you must memorise the tune to sing the succeeding printed verses, which are often on the next page (and not on an adjoining one). Only the first verse receives a precise melodic underlay, and even that is occasionally hard to decipher, when abbreviating devices are utilised (see, for example, the cramped format of S.4.21, song 2). Particularly difficult for the singer is the cramped textual underlay of the Voltaire setting (S.4.20), which must have resulted from a poorly planned engraving process.

Is it possible that the collection was never really conceived to be performed at all? Was it an expensive deluxe set that was primarily designed to be leafed through and admired, like a modern-day coffee-table book? This is indeed a distinct possibility. Laborde’s extremes of range seem to outline an idealised, almost inhuman, singer. Rousseau mentions that chansons like the romance should not “require too great an extent of the voice,” and certainly, Laborde’s ranges in the older style brunettes are more in keeping with a comfortable range.38 But the more operatically inflected chansons are wide-ranging and challenging.

There is much here that precludes what the eighteenth century called a “prima vista” performance, or a performance at sight. Laborde’s collection encourages you to work at the chanson. You must work out the words under the first verse and then you must memorise the melody so you can sing the other verses. You must practice the piece if you wish to deliver an effective performance that then looks and sounds easy and natural, as if it was sung prima vista. This kind of paradox, in which you must work hard for something to look and sound like it has not been laboured at, fits perfectly with contemporaneous reckonings of sensibilité itself, with its own contradictions of emotional and rational behaviour, or as Le Guin puts it, its “perpetual doubleness.”39 Diderot’s Paradoxe sur le Comédien goes to the heart of the matter:

One says that one weeps, but one does not weep when one pursues an effective adjective that eludes us; one says that one weeps, but one does not weep while occupied in rendering harmonious verse: or if tears flow, the quill falls from the hands, one gives into feeling and one ceases to compose.[40]

Diderot is here coincidentally describing the very act of a singer attempting to remember and “render harmonious verse.” You can’t be emotionally engaged in the chanson if you are working hard. Elsewhere, Diderot emphasises how performance interfaces and calibrates our genuine emotional reactions: “Wouldn’t you say, frankly, that true sensibilitié and performed sensibilité are two very different things?”41 As Monteclair notes, it is the performance of these songs that is so very challenging, in that one needs to both understand and perform the emotional states encapsulated within the text and music in addition to doing this with artistry.

I say “text and music” because an important—and unique—element now comes into play in the Choix des chansons: image.Laborde goes to greater lengths to help performers than any other contemporary composer and printer, and not the least is that the inclusion of imagery helps the performer and listener access and visualise these collections of diverse emotional states. Here Laborde is tapping into the theatricality of the opera house, in which scenes are played out as fantasy for an audience. The person leafing through the Choix des chansons witness these little scenes, in frozen tableaus. One is asked to imagine and to seek out, with the help of the aphorism beneath the image, what the scene means in context of the elaborate “histoire” or narrative of the chanson. It underscores the heart of the matter and aids in your cultivation of sensible empathy. It helps the performer play-act the chanson itself, and he or she might find themselves copying the dramatic gestures of the protagonists in the image in their own performance.

There are also several other subtle musical aids in the collection. First, Laborde and his engravers do try and help as much as possible with text-underlay. One song (S.4.22, song 2) exceptionally includes the different words for each verse under the same music. Other songs print out the verses under newly set music, with the accompanist continuing with music for verse 1. Here, though, is another performative challenge. The accompanist must now memorise the accompaniment if the vocalist turns the page to sing these verses. One really needs two copies to make these songs viable in performance (see S.1.19 without a page-turn, and S.3.13, S.3.17, and S.4.13, all with troublesome page-turns).

Second, the accompaniment is not a figured bass, but rather a written-out obligato part (and more on the nature of this accompaniment below). This decision must have vastly increased the labour of the engravers and of Laborde, in composing out these accompaniments. The collection could have been printed as single-line melodies, as in those many collections of brunettes, which would have arguably looked more elegant, but would have probably precluded effective performance in the salon, in which monody without accompaniment was probably risky for an amateur but also rather empty and anti-social. Figured bass would have increased the textural possibilities of different realisations, but just as the image freezes the flowing narrative into a single moment, so too does Laborde’s realisation capture the unique style of an accompanist. Here, it is the composer himself.

That the authorial voice is never far away in Laborde’s collection is not an accident, either in the history of music and the “work-concept” or indeed in Laborde’s own career.42 Enlightenment thinkers sought to imbue more authorial control with the composer, as one means of gaining control over a proliferating product. But Choix de chansons was arguably not meant for a large market, unlike Corrette’s treatises, for example. Rather it was an attempt to ingratiate Labrode with a new regime. But the authorial voice was important here too, as Laborde saw himself as the ideal curator of the wide diversity of French chansons. Although ultimately Laborde was not to find favour either with the new court or indeed with history in general, his Choix de chansons are in many ways a testament to important contemporary concerns about sensibilité and performance, about the struggles that eighteenth-century people had in finding “new ways to articulate individual feeling.”43 The challenges to performance that are in many ways at the heart of the Choix de chansons lie directly alongside Laborde and his creative team’s efforts to aid in that struggle. This is epitomised both in the emotional hyperreactivity of sensibilité itself, with all its paradoxes, as well as in the Choix de chansons itself, as we assess its unique performative power and emotional challenges.

Erin Helyard, University of Sydney, 2022

Notes

1. Jean-Benjamin de Laborde, Choix de chansons, 4 vols. (Paris: Lormel, 1773).

2. A good example with the same nomenclature as Laborde’s project is Moncrif’s collection from 1755 of ancient and modern chansons. ed. François-Augustin Paradis de Moncrif, Choix de chansons (Paris: [For the author], 1755).

3. Jean-Benjamin de Laborde, Choix de chansons, tirées des recueils de chansons (Paris: Prault, 1772), 3.

4. Gordon Ray, The Art of the French Illustrated Book: 1700-1914, vol. 1(New York: The Pierpont Morgan Library, 1982), 90. J. Lewine, Bibliography of Eighteenth-Century Art and Illustrated Books: Being a Guide to Collectors of Illustrated Works in English and French of the Period (London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1898), 267.

5. “La Borde aimait beaucoup sa musique, et avouait naïvement qu’aucune autre ne lui faisant autant de plaisir; elle est cependant fort médiocre, et aussi mal écrite que tout ce qu’on faisait alors en France. Cependant il a fait quelques chansons qui on du naturel; on remarque entre autres celle qui commence par ces mots: Vois-tu ces coteaux se noircir? celle qui a pour refrain L’Amour me fait; belle brunette, et Jupiter un jour en fureur. La Borde a publié avec beaucoup de luxe un Choix de chansons mises en musique à quatre parties […] L’harmonie en est fort mauvaise. On y trouve un grand nombre de gravures, dont exécution est aussi belle que le goût en est faux. Grimm a saisi toutes les occasions de maltraiter la musique de La Borde, dans sa correspondance littéraire ; elle est en effet bien plate et bien maussade.” Fétis, Biographie universelle des Musiciens et Bibliographie Générale de la Musique, (Brussels: Meline, Cans & Co., 1837), 270.

6. His indictment for execution by guillotine described him as an “ex-deputy fermier-général fattened by the substance of the people.” Emil Haraszti, “Jean-Benjamin de Laborde,” La revue musicale 158-9 (1935):109. For another unsympathetic account, see Alexandre Etienne Choron and François Joseph Fayolle, Dictionnaire historique des Musiciens [1810] (Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 1971).

7. Thomson, J. M., and John Wagstaff. “Printing and publishing of music.” In The Oxford Companion to Music: Oxford University Press. <https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/view/10.1093/acref/9780199579037.001.0001/acref-9780199579037-e-5360.> Donald Filar, “Jean-Benjamin de Laborde’s Abrégé d’un Traité de Composition: the merger of Musica Speculativa and Musica Pratica with an emerging Musica Historica” (PhD dissertation, Florida State University, 2005). Cynthia Gessele, “‘Base d’harmonie’: A Scene from Eighteenth-Century French Music Theory.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 119/1 (1994): 60–90. Zdravko Blazekovic, “Illustrations of Musical Instruments in Jean-Benjamin De La Borde’s Essai Sur La Musique Ancienne Et Moderne,” Musique–Images–Instruments: Revue Française d’Organologie Et d’Iconographie Musicale 15 (2015): 142–70. Jean-Benjamin de Laborde, Essai sur la musique ancienne et moderne (Paris: Onfroy, 1780).

8. Brigitte Level, Le Caveau, société bachique et chantante, 1726-1939: à travers deux siècles (Paris: Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 1988). Mathieu Couty, Jean-Benjamin de Laborde ou Le bonheur d’être fermier-général (Paris: Éditions TUM, 2001).

9. Darius Spieth, Napoleon’s Sorcerers: The Sophisians (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2007), 32.

10. Andy Clark and David Chalmers, “The Extended Mind,” Analysis 58 (1998): 7-19.

11. Abigail Williams, “The Poetry of the Un-enlightened: Politics and Literary Enthusiasm in the Early Eighteenth Century,” History of European Ideas 31 (2005): 299–311.

12. Andre Grenet, La littérature de sentiment au XVIIIe siècle. Tome 1. Les conquêtes de la sensibilité (Paris: Masson, 1971). Anne Coudreuse, “La rhétorique des larmes dans la littérature du XVIIIe siècle : étude de quelques exemples.” Modèles linguistiques 58 (2008): 147–162. Philip Stewart, L’Invention du sentiment: roman et économie affective au XVIIIe siècle (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2010). Elisabeth Le Guin, Boccherini’s Body: An Essay in Carnal Musicology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). Elisabeth Le Guin, ‘“One Says That One Weeps, but One Does Not Weep”: “Sensible”, Grotesque, and Mechanical Embodiments in Boccherini’s Chamber Music”, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 55/2 (2002): 207-254. James Webster makes a compelling case for regarding the onset of ‘sensibility’ as the beginning of a new music-historical period; see James Webster, ‘The Eighteenth Century as a Music-Historical Period?’, Eighteenth-Century Music, 1/1 (2004): 54.

13. Laborde, Choix de chansons, tirées des recueils de chansons (1772), 3.

14. Wye J. Allanbrook, Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), 16.

15. W. Dean Sutcliffe, Instrumental Music in an Age of Sociability (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

16. ed. anon., Recueil D’airs Choisis comme Brunêttes, Romances, Villageoises, Vaudevilles, Rondes & Autres, <https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb42634015d>

17. Christophe Ballard, Brunettes ou Petit airs tendres (Paris: [for the author], 1703), 3.

18. Gustave Cammaert, “Les Brunettes”, Revue belge de Musicologie 11:1/2 (1957): 35-51.

19. “Si le plus grand éloge de la musique est d’être souvent chantée, comme celui des vers est d’être fus par cœur, le succès & le mérite des vers que l’on présente ici au public sont également assurés. Qui n’a pas entendu chanter cent fois : Vois-tu ces côteaux se noircir, &c. Il est donc vrai Lucile, &c. Ah ! combien l’amour a des charmes ! &c. L’amant frivole & volage, &c. ; & tant d’autres vers pleins de grâce & de mélodie ? In ne faut pas s’attendre que dans un recueil de quatre volumes […] toutes les paroles sur lesquelles le Musicien a travaillé soient également agréables. D’ailleurs comme on voulait que la chanson fournît toujours une estampe les Auteurs des paroles en étaient plus gênés dans le choix des sujets, & plus excusables de ne pas toujours réussit. Mais le mérite du Compositeur en paraît plus grand, quand il faut qu’il supplée celui du Poëte. On trouvera ici beaucoup d’airs qu’on ne trouve point ailleurs.” Jean François de la Harpe, [Review of Choix des Chansons], Mercure de France (October 1775), 113-114.

20. Laborde, Essai, “Choix de chansons” in vol. 2, 159.

21. David Charlton, “Berlioz, Dalayrac and Song” in Berlioz and Debussy: Sources, Contexts and Legacies ed. by Barbara L. Kelly and Kerry Murphy (London: Routledge, 2016), 11.

22. Cited in Charlton, ibid., 12.

23. L’Affilard, Principes trés-faciles pour bien apprendre la musique (Paris: Ballard, 1717). Erich Schwandt, “L’Affilard’s Published ‘Sketchbooks’,” The Musical Quarterly 63/1 (1977): 99-113.

24. “[…] dont les chants naïfs, tendres et naturels les ont toujours soutenus malgré les atteintes, si souvent reïtereés, de ces pretendus savants qui ne trouvent rein de beau que ce qui les etonne et dont le gout usé ne peut estre piqué que par des chants detournés, par une modulation dure, par des transpositions forceés, par des dissonance continuèlles et entasseés les unes sur les autres […] L’avoüe cependant que l’art doit avoir des droits: un compositeur ne seroit pas consideré comme tel et ne meriteroit pas d’estre estimé, s’il ne produisoit que chansonnettes […] pour les petits Airs il faut, non seulement, avoir un genie naturel, un gout delicat, une disposition tendre […] mais il faut encore beaucoup d’Ame pour leur donner l’expression qu’ils demendent dont tres peu de gens sont capables. Les François peuvent se vanter, a juste titre, d’estre les seuls qui possedent le veritable gout de ces petittes pieces que les autres nations nomment, Bagatelles […]” Michel Pignolet de Monteclair, Brunetes anciènes et modernes (Paris: [for the author], c1720), 1.

25. ed. Christopher Murray, Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, Vol. 1 (London: Taylor & Francis, 2004), 955.

26. “[…] lancet indifféremment leurs traits sur le vice & sur la vertu, en les rendant également ridicules; ce qui doi proscrire le Vaudeville de la bouche des gens de bien.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Dictionnaire de la musique (Paris: Chez la Veuve Duschesne, 1768), 82.

27. ed. Pierre Colau, Les muses en goguettes, choix de chansons et rondes de table (Paris: Stahl, c1820).

28. L’amour quêteur (1777) in M. de Beaunoir, Théatre d’amour, vol. 1 (Paris: Cailleau, 1783). Anon., L’Apothéose (1780-85), https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb40251687n

29. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Les Consolations des misères de ma vie, our Recueil d’airs, romances, et duos (Paris: De Roullede de La Chevardière, 1781), 16-19.

30. “Chanson. Un petit poème lyrique fort court, qui roule ordinairement sur des sujets agréables, auquel on ajoute un air pour être chanté dans des occasions familières, comme à table, avec ses amis, avec sa maîtresse et même seul, pour éloigner quelques instants l’ennui, si l’on est riche, et pour supporter plus doucement la misère et le travail, si l’on est pauvre.” Rousseau, Dictionnaire, 77.

31. “Nous ajouterons à cette définition, que c’eft quelquefois un moyen ingénieux d’écrire l’histoire de sa vie & les différentes situations de son ame; de convenir publiquement de ce qu’on n’oserait peut-être pas avouer en particulier; & d’instruire allégoriquement l’objet aimé de ce qu’on souffre tant à lui cacher.” Laborde, Essai, vol. 2, 110.

32. Le Guin, ‘“One Says That One Weeps, but One Does Not Weep’,” 213.

33. “L’Editeur a mis un accompagnement de harpe à chacune des Chansons, en faveur des personnes qui jouent de cet instrument, devenu fort à la mode depuis quelque temps, & il aura grand soin qu’il ne se glisse aucune faute, ni dans les paroles, ni dans la Musique.” Laborde, Choix de chansons, tirées des recueils de chansons, 4.

34. Laborde, Essai, vol. 1, 297.

35. Michel Corrette, Nouvelle méthode pour apprendre à joeur de la harpe (Paris: [for the author], 1774).

36. “La Harpe entre vos mains Silvie, Ne laisse rien à desirer, De vox beaux yeux l’ame est ravie, Peut-on vous voir sans vous aimer!”

37. “Signifie aussi jouer des mains auprès d’une femme, la patiner, lui toucher la nature, la farfouiller avec les doigts, la clitoriser, la chatouiller avec les doigts.” Joseph Leroux, Dictionnaire comique, satyrique, burlesque, libres et proverbiale (Lyon: [for the author], 1785), p. 344-345.

38. “[…] qu’il n’exige pas une grande etendue de voix.” Rousseau, Dictionnaire, 427.

39. Le Guin, ‘“One Says That One Weeps, but One Does Not Weep’,” 230.

40. “On dit qu’on pleure, mais on ne pleure pas lorsqu’on poursuit une épithète énergique qui se refuse; on dit qu’on pleure, mais on ne pleure pas lorqu’on s’occupe à render son vers harmonieux: ou si les larmes coulent, la plume tombe des mains, on se livre à son sentiment et l’on cesse de composer.” Translation by Jacqueline Warwick, as quoted in Le Guin, ibid., 230. Denis Diderot, Paradoxe sur le Comédien in Oeuvres esthétiques, edited by Paul Vernière (Paris: Bordas, 1988), 333-334.

41. “Ne prononcez-vous pas nettement que la sensibilité vraie et la sensibilité jouée sont deux chose fort différentes?” Diderot, ibid., 357.

42. On the work-concept see Carl Dahlhaus, Grundlagen der Musikgeschichte (Köln, 1977); Walter Wiora, Das musikalische Kunstwerk (Tutzing, 1983) and “Das musikalische Kunstwerk der Neuzeit und das musikalische Kunstwerk der Antike” in Festschrift Carl Dahlhaus zum 60. Geburtstag, ed. Hermann Danuser et. al. (Laaber, 1988), p.3-10. Lydia Goehr, The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music (Oxford, 1992).

43. Le Guin, ‘“One Says That One Weeps, but One Does Not Weep’,” 207.